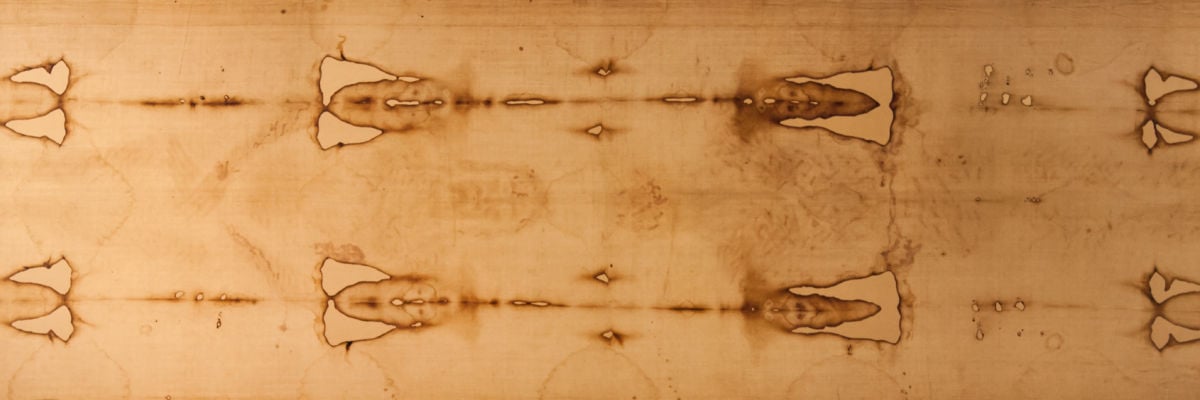

Shroud, THE HOLY.—This name is primarily given to a relic now preserved at Turin, for which the claim is made that it is the actual “clean linen cloth” in which Joseph of Arimathea wrapped the body of Jesus Christ (Matt., xxvii, 59). This relic though blackened by age bears the faint but distinct impress of a human form both back and front. The cloth is about 13.5 feet long and 4.5 feet wide. If the marks we perceive were caused by a human body, it is clear that the body (supine) was laid lengthwise along one half of the shroud while the other half was doubled back over the head to cover the whole front of the body from the face to the feet. The arrangement is well illustrated in the miniature of Giulio Clovio, which also gives a good representation of what was seen upon the shroud about the year 1540. The cloth now at Turin can be clearly traced back to Lirey in the Diocese of Troyes, where we first hear of it about the year 1360. In 1453 it was at Chambery in Savoy, and there in 1532 it narrowly escaped being consumed by a fire which, by charring the corners of the folds, has left a uniform series of marks on either side of the image. Since 1578 it has remained at Turin, where it is now only exposed for veneration at long intervals.

That the authenticity of the Shroud of Turin is taken for granted in various pronouncements of the Holy See cannot be disputed. An Office and Mass “de Sancta Sindone” was formally approved by Julius II in the Bull “Romanus Pontifex” of April 25, 1506, in the course of which the pope speaks of “that most famous shroud (praeclarissima sindon) in which our Savior was wrapped when He lay in the tomb and which is now honorably and devoutly preserved in a silver casket”. Moreover, the same pontiff speaks of the treatise upon the Precious Blood. composed by his predecessor Sixtus IV, in which Sixtus states that in this shroud “men may look upon the true blood and the portrait of Jesus Christ Himself”. A certain difficulty was caused by the existence elsewhere of other shrouds similarly impressed with the figure of Jesus Christ and some of these cloths, notably those of Besancon, Cadouin, Champiegne, Xabregas, etc., also claimed to be the authentic linen sindon provided by Joseph of Arimathea, but until the close of the last century no great attack was made upon the genuineness of the Turin relic. In 1898 when the shroud was solemnly exposed, permission was given to photograph it and a sensation was caused by the discovery that the image upon the linen was apparently a negative—in other words that the photographic negative taken from this offered a more recognizable picture of a human face than the cloth itself or any positive print. In the photographic negative the lights and shadows were natural, in the linen or the print they were inverted. Three years afterwards Dr. Paul Vignon read a remarkable paper before the Academie des Sciences in which he maintained that the impression upon the shroud was a “vaporigraph” caused by the ammoniacal emanations radiating from the surface of Christ’s body after so violent a death. Such vapours, as he professed to have proved experimentally, were capable of producing a deep reddish brown stain, varying in intensity with the distance, upon a cloth impregnated with oil and aloes. The image upon the shroud was therefore a natural negative and as such completely beyond the comprehension or the skill of any medieval forger.

Plausible as this contention appeared, a most serious historical difficulty had meanwhile been brought to light. Owing mainly to the researches of Canon Ulysse Chevalier a series of documents was discovered which clearly proved that in 1389 the Bishop of Troyes appealed to Clement VII, the Avignon pope then recognized in France, to put a stop to the scandals connected with the shroud preserved at Lirey. It was, the bishop declared, the work of an artist who some years before had confessed to having painted it, but it was then being exhibited by the canons of Lirey in such a way that the populace believed that it was the authentic shroud of Jesus Christ. The pope, without absolutely prohibiting the exhibition of the shroud, decided after full examination that in future when it was shown to the people the priest should declare in a loud voice that it was not the real shroud of Christ, but only a picture made to represent it. The authenticity of the documents connected with this appeal is not disputed. Moreover, the grave suspicion thus thrown upon the relic is immensely strengthened by the fact that no intelligible account, beyond wild conjecture, can be given of the previous history of the shroud or of its coming to Lirey.

An animated controversy followed and it must be admitted that though the immense preponderance of opinion among learned Catholics (see the statement by P. M. Baumgarten in the “Historisches Jahrbuch”, 1903, pp. 319-43) was adverse to the authenticity of the relic, still the violence of many of its assailants prejudiced their own cause. In particular the suggestions made of blundering or bad faith on the part of those who photographed the shroud were quite without excuse. From the scientific point of view, however, the difficulty of the “negative” impression on the cloth is not so serious as it seems. This shroud like the others was probably painted without fraudulent intent to aid the dramatic setting of the Easter Sequence:

Dic nobis Maria, quid vidisti in via Angelicos testes, sudarium et vestes.

As the word sudarium suggested, it was painted to represent the impression made by the sweat of Christ, i.e. probably in a yellowish tint upon unbleached linen, the marks of wounds being added in brilliant red. This yellow stain would turn brown in the course of centuries, the darkening process being aided by the effects of fire and sun. Thus, the lights of the original picture would become the shadow of the image as we now see it, but even in 1598 Paleotto’s reproduction of the images on the shroud is printed in two colors, pale yellow and red. As for the good proportions and esthetic effect, two things may be noted. First, that it is highly probable that the artist used a model to determine the length and position of the limbs, etc.; the representation no doubt was made exactly life size. Secondly, the impressions are only known to us in photographs so reduced, as compared with the original, that the crudenesses, aided by the softening effects of time, entirely disappear.

Lastly, the difficulty must be noticed that while the witnesses of the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries speak of the image as being then so vivid that the blood seemed freshly shed, it is now darkened and hardly recognizable without minute attention. On the supposition that this is an authentic relic dating from the year A.D. 30, why should it have retained its brilliance through countless journeys and changes of climate for fifteen centuries, and then in four centuries more have become almost invisible? On the other hand if it be a fabrication of the fifteenth century this is exactly what we should expect.

HERBERT THURSTON