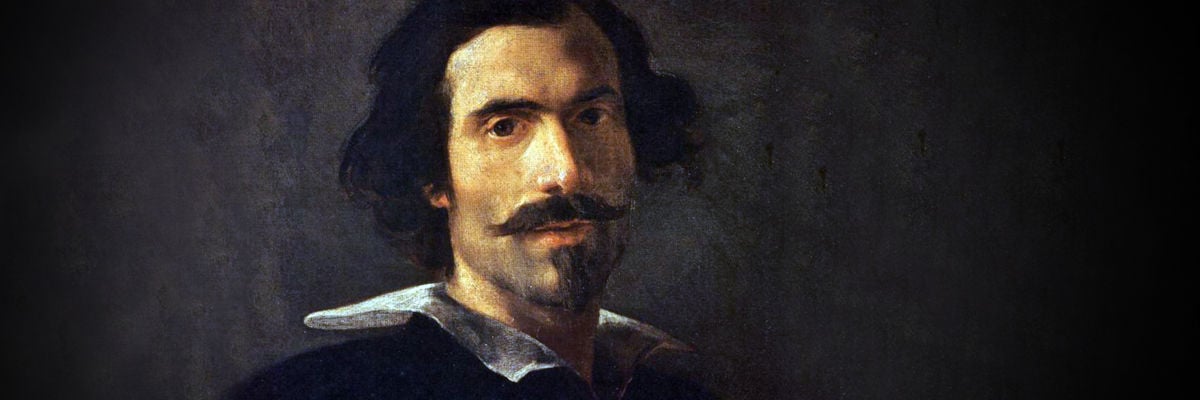

Bernini, GIOVANNI LORENZO, one of the most vigorous and fertile of Italian architects and sculptors, b. at Naples in 1598; d. at Rome in 1680. Bernini in his art is the most industrious of Roman artists, and his work tends largely to the baroque. In addition to his abilities as sculptor and architect he possessed those of a painter and even of a poet. His father, a painter and sculptor of moderate skill, gave him his first lessons in art. In 1608 the father was called to Rome and took Lorenzo with him. It is said that the boy even in his eighth year had carved a beautiful marble head of a child; in his fifteenth year he produced the “David with a Sling” which is now in the Villa Borghese. Paul V employed him, and under the five following popes he rose to great fame and importance. He was the favorite of Urban VIII (Barberini). In 1629 he became the architect of St. Peter’s and superintendent of Public Works in Rome. He ruled in art like a second Michaelangelo, although his style bore little resemblance to that of the latter. Mazarin tried in 1664 to persuade him to come to Paris, but he did not visit that city until 1665 when he accepted an invitation from Louis XIV. A son named Paul and a numerous suite accompanied him to Paris and Versailles. Jealousy, however, prevented the carrying out of his plans for the Louvre, nor was he able to maintain himself long in Paris. His pupil, Mathias Rossi, was also forced, not long after the master’s departure, to leave the city. The king, however, treated Bernini with great honor during his stay and rewarded him munificently. Bernini made a bust and an equestrian statue of Louis XIV which were in a style agreeable to the taste of that monarch. Queen Christina of Sweden visited Bernini during her stay in Rome; and on an order of King Philip IV he made a huge crucifix for the royal mortuary chapel. He also carved busts of Charles I of England and his wife Henrietta. Bernini triumphed over all his detractors and became in the end as rich as he was famous.

It is not necessary to speak here of his writings and of his comedies in verse. Nor need mention be made of his paintings which amount to some two hundred canvases. He owes his fame to his architectural work, for which he had in Rome great and inspiring examples. He never lacked imagination, inventive power, or courage in undertaking a task. He did not copy the simplicity of the antique and often deliberately departed from the canons of art in the hope of excelling them (chi non esce talvolta della regola, non la passa mai). The art of this period in aiming at outward effect lost all moderation and went to too great an extreme. In completing the church of St. Peter Bernini was naturally obliged to exert all his powers. As the seventh architect engaged in the work he gave the finishing touches to the great undertaking. With sound judgment he followed the plan of Maderna—to increase the effect of the facade by means of flanking towers. He wished, however, to make the towers a more important feature than in Maderna’s scheme. keeping them though in such proportion that in the distance they should appear some thirty metres below the dome. As one tower was well under way it fell down on account of the weakness of the foundation laid by Maderna. One of the most brilliant works of Bernini is the colonnade before St. Peter’s. It proves the truth of the axiom he laid down: “An architect proves his skill by turning the defects of a site into advantages”. The slope of the ground from the doorway of the basilica to the bridge over the Tiber suggested the scheme of laying out the great stairway of twenty-two steps and the great and equally well-conceived terrace. The ground available being limited on two sides by neighboring houses, Bernini avoided the danger of coming too close to the buildings by adopting the beautiful elliptic form of the colonnade, which encloses, nevertheless, as large a ground-surface as the Colosseum.

The avenue thus formed is perhaps the most beautiful one in the world. When the piazza is approached from the distance a fine view is at first obtained of the dome; unfortunately the dome is more and more obscured, on nearer approach, by the portico and the facade of the church. Four rows of Tuscan columns, placed to right and left and having altogether the form of an ellipse, traverse the piazza from one end to the other. Between the middle rows of columns two carriages can pass. The slope of the ground without being sharp enough to produce fatigue causes the eye to look steadily upward. In the middle of the ellipse, which is 895×741 feet, stands the obelisk, 84 feet high, which was placed here in 1586 by Sixtus V. Back of the ellipse rises the terrace. Two galleries unite the ellipse with the portico, the height of which is best realized by comparing it with these galleries. Everything here is on a great scale. When, however, the pope gives the blessing from the balcony, the convergence of the lines in the arrangement of the piazza causes the space to appear much greater than it really is. The stairway (Scala Regia), which ascends from the portico to the Sala Regia, offers a fine perspective. Limitation was here turned into a source of beauty. Bernini had a large share in the erection of the stately Barberini palace at Rome. He built the beautiful Odescalchi palace, took part in adorning the Piazza Navona with the obelisk, and designed the pleasing statues of the river-gods for the great fountain.

In speaking of Bernini’s work as a sculptor it may be said that in this field the decadence of his art makes itself apparent. The skeleton representing Death on the tomb of Urban VIII, in the church of St. Peter, is placed in the midst of ideal and really beautiful figures. Weaker still, with the exception of the portrait, is the tomb of Alexander VII. “St. Theresa pierced by an Arrow” is exceedingly effective, the “‘Rape of Proserpine”, as well as his “Apollo and Daphne”, are weak and sensuous. On the other hand, the equestrian statue of Constantine in St. Peter’s suffers from its size, as the heroic proportions do not appear to be united with the necessary intrinsic worth. Today the canopy (baldacchino) is as universally condemned as it was then (1633) admired. Neither is approval now given to the “Chair of St. Peter” in the tribune of the basilica. Viewed as a sculptor Bernini is at times extreme, without force, theatrical in the pose, affected in details, or over-luxuriant in physical graces. He was entirely in accord with the spirit of his time and countenanced it with all the authority of his ability and fame. He attached more importance to grace of outward form than to intrinsic merit, and aimed more at external effect than at the real artistic completeness of the work. Yet among his productions as a sculptor are many excellent works. As examples may be given the tomb of the Countess Matilda in St. Peter’s, and the statues of St. Ludovica Albertoni and St. Bibiana in the niches of the colonnade of St. Peter’s. In the niches of these columns are 162 statues made after designs by Bernini. In his work on the Bridge of Sant’ Angelo he shows at least wonderful richness of design. He by no means failed in designs for tombs and in portrait busts; for example, the bust of his daughter and that of Innocent X.

He often spoiled the pure plastic effect of his work by two or three false conceptions. He held that the antique repose of sculpture, which, it must be acknowledged, at times nearly degenerates into stiffness, must be transformed into effective action at any cost. The naturalistic painting of the time drove the sculptors into this course. But in the plastic arts the reason for extreme action is often not clear and it appears weak, sentimental, and theatrical. When the work is executed in polished marble, for which Bernini had a strong predilection, over-action is apt to degenerate into the opposite of what is intended and to become an extreme ugliness, or a miscarried attempt at grandeur. On account of these misconceptions of art Bernini’s work was often a failure. The style of sculpture which aims solely at outward effect is seen to best advantage when it is used in connection with architecture. The statues designed by Bernini for the facade of St. Peter’s and of the Lateran belong to this form of art. Action appears at its best in sculpture when used as decoration and on a small scale. The decorative architectural style is better suited, therefore, for relief work than for sculpture in the round.

G. GIETMANN