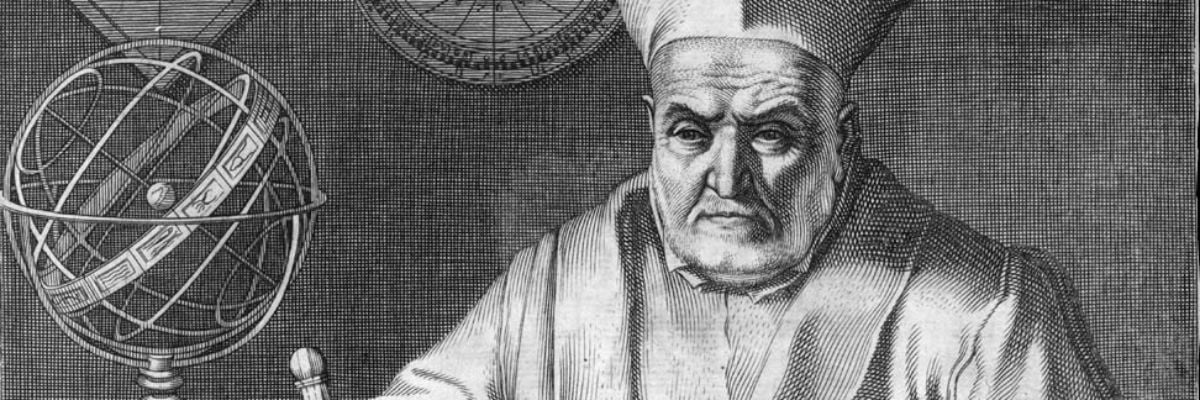

Clavius, CHRISTOPHER (CHRISTOPH CLAU), mathematician and astronomer, whose most important achievement related to the reform of the calendar under Gregory XIII; b. at Bamberg, Bavaria, 1538; d. at Rome, February 12, 1612. The German form of his name was latinized into “Clavius”. He entered the Society of Jesus in 1555 and his especial talent for mathematical research showed itself even in his preliminary studies at Coimbra. Called to Rome by his superiors as teacher of this branch of science at the well-known Collegium Romanum, he was engaged uninterruptedly there until his death. The greatest scholars of his time, such men as Tycho Brahe, Johann Kepler, Galileo Galilei, and Giovanni Antonio Magini, esteemed him highly. He was called the “Euclid of the sixteenth century”; and even his scientific opponents, like Scaliger, said openly that they would rather be censured by a Clavius than praised by another man. There has, however, been no lack of persistent disparagement of Catholic scholars even down to our own times; and therefore much that is inexact, false, and mythical has been put into circulation about Clavius, as for example that he was originally named “Schlussel” (clavis, “key”), that he was appointed a cardinal, that he met his death by the thrust of a mad bull, etc. His relations with Galilei, with whom he remained on friendly terms until his death, have also been often misrepresented. The best evidence of the actual achievements of the great man is presented by his numerous writings, which at the end of his life he reissued at Mainz in five huge folio volumes in a collective edition under the title, “Christophori Clavii e Societate Jesu opera mathematica, quinque tomis distributa”. The first contains the Euclidean geometry and the “Spheric” of Theodosius (Sphiericorum Libri III); the second, the practical geometry and algebra; the third is composed of a complete commentary upon the “Sphmra” of Joannes de Sacro Bosco (John Holy-wood), and a dissertation upon the astrolabe; the fourth contains what was up to that time the most detailed and copious discussion of gnomonics, i.e. the art of constructing all possible sundials; finally, the fifth contains the best and most fundamental exposition of the reform of the calendar accomplished under Gregory XIII.

Many of these writings had already appeared in numerous previous editions, especially the “Commentarius in Spharam Joannis de Sacro Bosco” (Rome, 1570, 1575, 1581, 1585, 1606; Venice, 1596, 1601, 1602, 1603, 1607; Lyons, 1600, 1608, etc.); likewise the “Euclidis Elementorum Libri XV” (Rome, 1574, 1589, 1591, 1603, 1605; Frankfort, 1612). After his death also these were republished in 1617, 1627, 1654, 1663, 1717, at Cologne, Frankfort, and Amsterdam, and were even translated into Chinese. In his “Geometria Practica” (1604) Clavius states among other things a method of dividing a measuring scale into subdivisions of any desired smallness, which is far more complete than that given by Nonius and must be considered as the precursor of the measuring instrument named after Vernier, to which perhaps the name Clavius ought accordingly to be given. The chief merit of Clavius, however, lies in the profound exposition and masterly defense of the Gregorian calendar reform, the execution and final victory of which are due chiefly to him. Cf. “Romani calendarii a Gregorio XIII restituti explicatio” (Rome, 1603); “Novi calendarii Romani apologia (adversus M. Maestlinum in Tubingensi Academia mathematicum)” (Rome, 1588). Distinguished pupils of Clavius were Grienberger and Blancanus, both priests of the Society of Jesus.

ADOLF MULLER