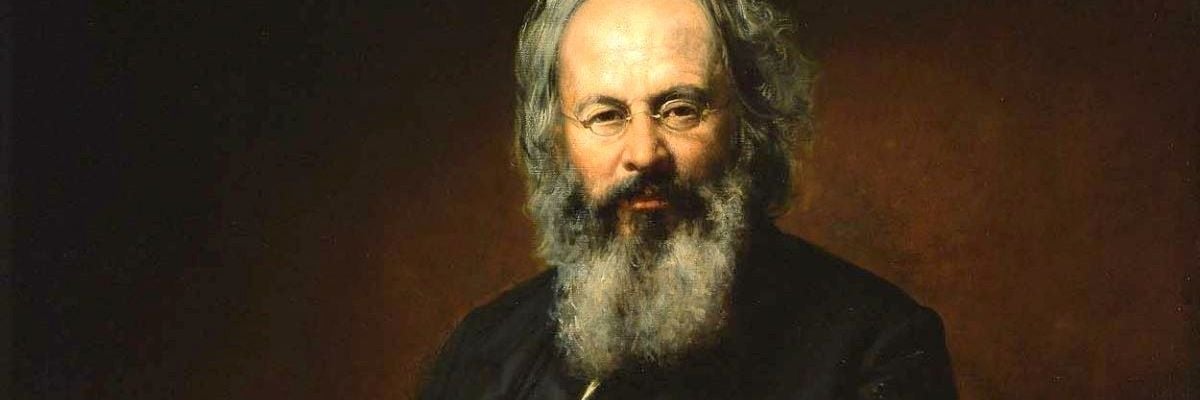

Brownson, ORESTES AUGUSTUS, philosopher, essayist, reviewer, b. at Stockbridge, Vermont, U.S.A., September 16, 1803; d. at Detroit, Michigan, April 17, 1876. His childhood was passed on a small farm with plain country people, honest and upright Congregationalists, who treated him with kindness and affection, taught him the Lord’s Prayer, the Apostles’ Creed, and the Assembly’s Catechism; to be honest and industrious, truthful in all circumstances, and never to let the sun go down on his wrath. With no young companions, his fondness for reading grew rapidly, though he had access to few books, and those of a grave or religious nature. At the age of nineteen he had a fair knowledge of grammar and arithmetic and could translate Virgil’s poetry. In October, 1822, he joined the Presbyterian Church, dreamed of becoming a missionary, but very soon felt repelled by Presbyterian discipline, and still more by the doctrines of unconditional election and reprobation, and that God foreordains the wicked to sin necessarily, that He may damn them justly. Rather than sacrifice his belief in justice and humanity on the altar of a religion confessedly of human origin and fallible in its teachings, Brownson rejected Calvinism for so-called liberal Christianity, and early in 1824, at the age of twenty avowed himself a Universalist. In June, 1826, he was ordained, and from that time until near the end of 1829, he preached and wrote as a Universalist minister, calling himself a Christian; but at last denying all Divine revelation, the Divinity of Christ, and a future judgement, he abandoned the ministry and became associated with Robert Dale Owen and Fanny Wright in their war on marriage, property, and religion, carried on in the “Free Enquirer” of New York, of which Brownson, then at Auburn, became corresponding editor. At the same time he established a journal in western New York in the interest of the Workingmen’s Party, which they wished to use for securing the adoption of their system of education. But, besides this motive, Brownson’s sympathy was always with the laboring class, and he entered with ador on the work of elevating labor, making it respected and as well rewarded in its manual or servile, as in its mercantile or liberal, phases, and the end he aimed at was moral and social amelioration and equality, rather than political. The introduction of large industries carried on by means of vast outlays of capital or credit had reduced operatives to the condition of virtual slavery; but Brownson soon became satisfied that the remedy was not to be secured by arraying labor against capital by a political organization, but by inducing all classes to cooperate in the efforts to procure the improvement of the workingman’s condition. He found, too, that he could not advance a single step in this direction without religion. An unbeliever in Christianity, he embraced the religion of Humanity, severed his connection with the Workingmen’s Party and with “The Free Enquirer”, and on the first Sunday in February, 1831, began preaching in Ithaca, New York, as an independent minister. As a Universalist, he had edited their organ, “The Gospel Advocate”; he now edited and published his own organ, “The Philanthropist.”

Finding, from Dr. W. E. Channing’s printed sermons, that Unitarians believed no more of Christianity than he did, he became associated with that denomination, and so remained for the next twelve years. In 1832 he was settled as pastor of the Unitarian Church at Walpole, New Hampshire; in 1834 he was installed pastor of the First Congregational Church at Canton, Massachusetts; and in 1836 he organized in Boston “The Society for Christian Union and Progress”, to which he preached in the Old Masonic Temple, in Tremont Street. After conducting various periodicals, and contributing to others, the most important of which was “The Christian Examiner”, he started a publication of his own called “The Boston Quarterly Review”, the first number of which was dated January, 1838. Most of the articles of this review were written by him; but some were contributed by A. H. Everett, George Bancroft, George Ripley, A. Bronson Alcott, Sarah Margaret Fuller, Anne Charlotte Lynch, and other friends. Besides his articles on literary and philosophical subjects, his political essays in this review attracted attention throughout the country and brought him into close relations with the leaders of the Democratic Party. Although a steadfast Democrat, he disliked the name Democrat, and denounced pure democracy, called popular sovereignty, or the rule of the will of the majority, maintaining that government by the will, whether that of one man or that of many, was mere arbitrary government, and therefore tyranny, despotism, absolutism. Constitutions, if not too easily alterable, he thought a wholesome bridle on popular caprice, and he objected to legislation for the especial benefit of any individual or class; privileges, i.e. private laws; exemption of stockholders in corporations from liability for debts of their corporation; tariffs to enrich the moneyed class at the expense of mechanics, agriculturists, and members of the liberal professions. He demanded equality of rights, not that men should be all equal, but that all should be on the same footing, and no man should make himself taller by standing on another’s shoulders.

In his “Review” for July 1840, he carried the democratic principles to their extreme logical conclusions, and urged the abolition of Christianity; meaning, of course, the only Christianity he was acquainted with, if indeed, it be Christianity; denounced the penal code, as bearing with peculiar severity on the poor, and the expense to the poor in civil cases; and, accepting the doctrine of Locke, Jefferson, Mirabeau, Portalis, Kent, and Blackstone, that the right to devise or bequeath property is based on statute, not on natural, law, he objected to the testamentary and hereditary descent of property; and, what gave more offense than all the rest, he condemned the modern industrial system, especially the system of labor at wages. In all this he only carried out the doctrine of European Socialists and the Saint-Simonians. Democrats were horrified by the article; Whigs paraded it as what Democrats were aiming at; and Van Buren, who was a candidate for a second term as President, blamed it as the main cause of his defeat. The manner in which he was assailed aroused Brownson’s indignation, and he defended his essay with vigour in the following number of his “Review”, and silenced the clamors against him, more than regaining the ground he had lost, so that he never commanded more attention, or had a more promising career open before him, than when, in 1844, he turned his back on honors and popularity to become a Catholic. At the end of 1842 the “Boston Quarterly Review” was merged in the “U.S. Democratic Review”, of New York, a monthly publication, to each number of which Brownson contributed, and in which he set forth the principles of “Synthetic Philosophy” and series of essays on the “Origin and Constitution of Government”, which more than twenty years later he rewrote and published with the title of “The American Republic”. The doctrine of these essays provoked such repeated complaints from the editor of the “Democratic Review”, that Brownson severed his connection with that monthly and resumed the publication of his own review, changing the title from “Boston” to “Brownson’s Quarterly Review”. The first number was issued in January, 1844, and the last in October, 1875. From January, 1865, to October, 1872, he suspended its publication.

The printed works of Brownson, other than contributions to his own and other journals, from the commencement of his preaching to the establishment of this review consisted of his sermons, orations, and other public addresses; his “New Views of Christianity, Society, and the Church” (Boston, 1836), in which he objected to Protestantism that it is pure materialism to Catholicism, that it is mere spiritualism, and exalts his “Church of the Future” as the synthesis of both; “Charles Elwood” (Boston, 1840), in which the infidel hero becomes a convert to what the author calls Christianity and makes as little removed as possible from bald deism; and “The Mediatorial Life of Jesus” (Boston, 1842), which is almost Catholic, and contains a doctrine of life which leads to the door of the Catholic Church. He soon after applied to the Bishop of Boston for admission, and in October, 1844, was received by the Coadjutor Bishop, John B. Fitzpatrick.

The Catholic body in the United States was at that time largely composed of men and women of the laboring class, who had emigrated from a country in which they and their forefathers had suffered centuries of persecution for the Faith, and had too long felt themselves a down-trodden people to be able to lift their countenances with the fearless independence of Americans; or, if their were better-to-do, feared to make their religion prominent and extended to those of other faiths the liberal treatment they hoped for in return. It was Brownson’s first labor to change all this. He engaged at once in controversy with the organs of the various Protestant sects on one hand, and against liberalism, latitudinarianism, and political atheism of Catholics, on the other. The American people, prejudiced against Catholicity, and opposed to Catholics, were rendered more prejudiced and opposed by their tame and apologetic tone in setting forth and defending their Faith, and were delighted to find Catholics laboring to soften the severities and to throw off whatever appeared exclusive or rigorous in their doctrine. But Brownson resolved to stand erect; let his tone be firm and manly, his voice clear and distinct, his speech strong and decided. So well did he carry out this resolution, and so able and intrepid an advocate did he prove in defense of the Faith, that he merited a letter of approbation and encouragement from the Bishops of the United States assembled in Plenary Council at Baltimore, in May, 1849, and from Pope Pius IX, in April, 1854. In October, 1855, Brownson changed his residence to New York, and his “Review” was ever after published there—although, after 1857, he made his home in Elizabeth, New Jersey, till 1875, when he went to live in Detroit, where he died in the following April. A little over a year before moving to New York, he wrote, “The Spirit Rapper” (Boston, 1854), a book in the form of a novel and a biography, visionary reforms, socialism, revolutionism; with the aim of recalling the age to faith in the Gospel. His next book, written in New York, was “The Convert; or, Leaves from my Experience” (New York, 1857), tracing with fidelity his entire religious life down to his admission to the bosom of the Catholic Church.

Brownson had not been many years in New York before the influence of those Catholics with whom he mainly associated was perceptible in the tone of his writings, in the milder and almost conciliatory attitude towards those not of the Faith, which led many of his old admirers to fear he was becoming a “liberal Catholic“. At the same time, the War of the Rebellion having broken out, he was most earnest in denouncing Secession and urging its suppression, and as a means to this, the abolition of slavery. This alienated all his Southern and many of his Northern supporters. Domestic affliction was added by the death of his two sons in the summer of 1864. In these circumstances, he felt unable to go on with his “Review”, and in October of that year announced its discontinuance. But he did not sit idle. During the eight years that followed, he wrote “The American Republic; Its Constitution, Tendencies, and Destiny” (New York, 1865); leading articles in the New York Tablet”, continued till within a few months of his death; several series of articles in “The Ave Maria”; generally one or two articles a month in “The Catholic World”; and, instructed by the “Syllabus of Errors” condemned by Pope Pius IX, “Conversations on Liberalism and the Church” (New York, 1869), a small book which shows that if, for a short period of his Catholic life, he parleyed with Liberalism, he had too much horror of it to embrace it. In January, 1873, “Brownson’s Quarterly Review” appeared again and regularly thereafter till the end of 1875. His last article was contributed to the “American Catholic Quarterly Review”, for January, 1876. Brownson always disclaimed having originated any system of philosophy and acknowledged freely whatever he borrowed from others; but he had worked out and arrived at substantially the philosophy of his later writings before he ever heard of Gioberti, from whom he obtained the formula ens creat existentias, which Gioberti expressed in the formula ens creat existens, to indicate the ideal or intelligible object of thought. By the analysis of thought he finds that it is composed of three inseparable elements, subject, object, and their relation, simultaneously given. Analysis of the object shows that it is likewise composed of three elements simultaneously given, the ideal, the empirical, and their relation. He distinguished the ideal intuition, in which the activity is in the object presenting or offering itself, and empirical intuition or cognition, in which the subject as well as the object acts. Ideal intuition presents the object, reflection takes it as represented sensibly; that is, in case of the ideal, as represented in language. Identifying ideas with the categories of the philosophers, he reduced them to these three: Being, Existences, and their Relations. The necessary is Being; the contingent, Existences, and their relation, the creative act of Being. Being is God, personal because He has intelligence and will. From Him, as First Cause, proceed the physical laws; and as Final Cause, the moral law, commanding to worship Him, naturally or supernaturally, in the way and manner He prescribes.

SARAH M., daughter of Orestes A. Brownson, b. at Chelsea, Massachusetts, June 7, 1839; married William J. Tenney, of Elizabeth, New Jersey, November 26, 1873; died at Elizabeth, October 30, 1876. She wrote some literary criticisms for her father’s “Review”, and many articles, stories, and poems which appeared mainly in Catholic magazines. Her other works were: “Marian Elwood, or How Girls Live” (New York, 1863); “At Anchor; a story of the American Civil War” (New York, 1865); “Heremore Brandon; or the Fortunes of a Newsboy” (in “The Catholic World”, 1869); and “Life of Demetrius Augustine Gallitzin, Prince and Priest” (New York, 1873). Her novels are interesting, genuine, and original, and all that she published is stamped with her distinguishing traits of character, and shows that she thought for herself, expressed herself freely, with good sense and judgement, without undue bitterness, and with great benevolence towards the poor; and she scatters over her pages many excellent reflections. The life of Gallitzin is her principal production, for which she spared no pains to collect such materials as remained. She more than once visited the scenes of the missionary’s labors, and formed the acquaintance of priests and others who had known him, collecting such facts and anecdotes of him as they remembered. It is a sincere and conscientious tribute to the rare virtues and worth of an extraordinary man, devoted priest, and humble missionary.

HENRY F. BROWNSON