Audio only:

Joe Heschmeyer explores the complex theological implications of Judas’ betrayal, examining whether Jesus’ choice of Judas suggests a deeper, potentially troubling divine plan.

Transcription:

Joe:

Welcome back to Shameless Popery; I’m Joe Heschmeyer and today I want to look at the problem of Judas. What do I mean by that? At the last supper, Jesus says of Judas, the son of man goes as it is written of him, but woe to that man by whom the son of man is betrayed. It would’ve been better for that man if he’d never been born and we might object here. Jesus, you are the one who caused Judas to be born in the first place, so surely there’s something mysterious here. Why did you create Judas if you think it would be better that he had not been born? But it’s not just that Jesus created Judas and caused him to be born. He called him to be one of the apostles, and Jesus doesn’t run from this apparent scandal either. He seems to lean into it.

At the end of John six, he says, did I not choose you? The 12 and one of you is a devil, and in case we miss it, John then explains, he spoke of Judas, the son of Simon Sct, for he, one of the 12 was to betray him. It almost looks like Jesus called Judas as an apostle so that he would betray him. So is that right? Does Jesus want Judas to sin or does he cause his sin in some way or it can certainly sound like that and frankly, there’s no shortage of Protestant ministers who suggest that might be the case. It might even sound like that from the words of the Bible. In addition to what we just saw, acts four has this really fascinating part in which the apostles and the early Christians are praying together and they praise God for the fact that truly in this city, Jerusalem, they were gathered together against thy holy servant Jesus, whom now dis anoint both Herod and punch his Pilate with the Gentiles and the people of Israel to do whatever thy hand and thy plan had predestined to take place.

Now, Judas isn’t mentioned by name there, but surely alongside Herod and Pontius Pilate and the Gentile and Jewish leaders of the day who are responsible for Jesus’ death, we can add Judas to the list and say somehow the biblical answer to the question appears to involve this thorny question of predestination. So I want to try to answer that today and explain what the Bible does and doesn’t mean by talking about God predestining things. But before we get there, we need to talk actually about two ways seemingly opposite, but I would suggest actually quite similar in which Christians have historically gotten the story of Judas wrong. These are the two, again, at the surface opposite, maybe not so opposite ways we can screw up in thinking about the story of Judas, the first way is to treat Judas as the hero. Now, most of us I think would not fall into this trap, but it can be sort of tempting to view the whole thing.

Look, Judas is betrayal led to the greatest act of human history. Jesus Christ laying down his life forth the salvation of the world. So maybe some people have claimed throughout history, Judas is actually an underappreciated good guy. Now, the most famous and maybe most notorious example of this is the so-called Gospel of Judas. This is one of those gnostic gospels. So it’s heavily influenced by the gnostic heresy. It claims to be a recording of what Jesus revealed to Judas. It’s actually from much later like the mid second century at least I would say. But in there it depicts Jesus secretly talking with Judas about how he’s going to go above and beyond the others because he’ll sacrifice the human who bears me. Now to make sense of that, you need to know something about gnosticism. It says the body is bad, the body’s a prison.

So in this view, what’s so good about the crucifixion is that Jesus, this divine spirit is free from the prison of the mortal body. Obviously this is not sound theology, but you’ll notice going pretty far back in Christian history, this desire to sort of want to excuse Judas or even to treat him as a hero because of the goodness that comes from Good Friday. The second view on the surface might seem to be the opposite because this isn’t early gnostics. This is modern day Protestants of the Calvinist variety, and I’m going to provocatively call their view. They view that Judas died for our sins. Now, that’s not how they would say it. I want to say that upfront. I want to suggest that’s where their theology leads and that this is something that if you’re inclined to view Judas in this way, you should watch out for because you can subtly without meaning to put Judas in the place of Jesus.

What do I mean by that? In John 11, Caiaphas, the high priest is part of a group conspiring to have Jesus killed in Caiaphas we’re actually told by John, inspired by the Holy Spirit prophesize to the people you do not understand that it is expedient for you that one man should die for the people that the whole nation should not perish. Now, he means something evil by that, but John makes the point. This is actually prophetic. Jesus would in fact die for the nation and not for the nation only, but for the Gentiles as well to gather into one the children of God who are scattered abroad. So I want to have you think about that. So the classic Christian conception is Jesus undergoes the horrors of the cross and all of this in some way to die for our sins. Now how that works is a whole other can of worms Christians sometimes disagree about, but that’s the core idea and it strikes me that there’s something really similar going on in how certain Calvinist preachers talk about the role of Judas. Now, I’ve picked on John MacArthur before because he’s extremely popular and wrong on a lot of things, and I hope you’ll forgive me for picking on him one more time, but I can’t resist addressing some of the errors that he presents in his presentation of the betrayal of Judas. So he begins by talking about how Jesus treats Judas like a friend. Hey,

CLIP:

Judas had been allowed by our Lord to be in the position on his side where the honored guest would sit. And so our Lord in a gesture of amazing honor to Judas gives him the morsel as if he were some honored guest, a mark of special affection, place of honor, place of an intimate friend.

Joe:

Okay, so we’re going to get into this whole idea of Jesus’s friendship with Judas later on because that’s actually a really important theological theme that I don’t hear many people talk about at all. But MacArthur is going to present it as if Jesus is acting like he’s Judas friends, but then when he gets to John 13 where Jesus gives a morsel to Judas,

Satan were told enters Judas. No, in context, Jesus has announced that he’s going to be betrayed and Judas has already plotted to betray him. So it isn’t as if Judas was a really good guy and then he’s just overcome by the devil and can’t help himself. He’s already been planning to betray Jesus. It’s very clear from all four gospels at this point though, at the last supper we’re told that Satan enters into Judas. Jesus then says to him, what you’re going to do do quickly. Now when you or I read that, we might read that for what it is that he’s just saying, get this bad thing you’re going to do over with. He’s not encouraging him to do the bad thing, but in the same way that for instance, someone about to be unjustly executed might say, get it done with, they’re not saying, please execute me, but they are saying don’t drag it out. If you’ve decided you’re going to do the evil thing, that’s not an encouragement to do evil, right? Well, according to MacArthur, it not only is it’s actually a divine command to do evil,

CLIP:

But with the statement of Jesus, what you do do quickly, he activated his own death. That is step one in the activation of his own execution because nothing will be happening until the trigger is pulled, and Judas is the trigger

He

Judas acted. Verse 30, he had no choice, sovereign Lord,

Joe:

That’s a fascinating claim. He says Judas acted he had no choice, sovereign Lord, in those six words, John MacArthur has just turned Jesus’s self-sacrifice into a suicide that Jesus holds the gun to his head and pulls the trigger, and the trigger really is not responsible. Guns don’t kill people, people kill people. I’ve heard that a thousand times, Judas is just the trigger. Jesus is committing suicide. That’s the problem with this theology at the outset, but think about the implications for Judas. If a gun kills someone, you don’t put the gun on trial. It had no agency, it had no free will. He just said Judas had no free will. So surely you might think Judas will at least get off the hook. He won’t be punished for something he had literally no control over. Well, not so it says MacArthur,

CLIP:

As I said, Judas would never see another day and by the dawning of the next day, Jesus’ trial would be essentially over and he’d be on his way to death. Jesus would come out the other side of the grave to eternal glory. Judas would be damned to hell forever.

Joe:

Again, though, if Judas is just a trigger, why in the world is he damned forever? And for that matter, if Judas has no free will, why not at least bring him to redemption? This is a notoriously sticky problem for Calvinists that if the only thing that matters here is God’s sovereignty and Judas is presented as Jesus’s friend, why would Jesus not save his friend? Well, according to John Piper, it’s because he didn’t actually want to.

CLIP:

Judas didn’t repent because it was not granted to him by the father.

Joe:

This is what I mean where it appears that Jesus and Judas have been reversed. Whereas in the biblical account, Judas betrays the friendship of Jesus and sends him to his death so that one man can die for the nation, whether he knows that’s why that’s happening or not. In the Calvinist view, it almost seems as if Jesus is only pretending to be Judas, his friend, while having no intention of saving him, no intention of bringing him to regeneration, no intention of bringing him to eternal life, but instead is using him, pretending to be his friend and betraying him so that Judas will go to hell forever. Why? Because he needs a trigger to launch the plan of salvation. So Judas has to die so that we may live. Judas is the sort of substitutionary atonement in that theology. If you draw that logic out, that’s what it would appear to suggest. Now, again, I’m sure that people who say that don’t think that through to that conclusion, but nevertheless, they do say some bizarre things that make it sound like they’re really grateful for Judas or like what he did was actually good and not tremendously evil. For instance, here’s RC sprawl.

CLIP:

From one perspective, we see that the most evil action in the history of the world was committed by Judas. On the other hand, from a different perspective, the most glorious deed that ever was performed in our behalf was the betrayal of Jesus Christ. Because through that work that orchestrated by God’s sovereignty, our salvation came to pass.

Joe:

I want to make sure you don’t miss what he just said. He just said that the most glorious deed ever performed on our behalf was not Jesus’s self-sacrificial death on the cross. The most glorious deed ever performed on our behalf was the betrayal of Jesus Christ by Judas Escar, that Judas, not Jesus performed the greatest act in history. It would be impossible to get that more wrong. Judas did what Christians have historically believed to be the single worst act in all of history. And RC Spro says, actually, it’s the best. Sure, from one perspective it’s really bad, but because God drew good out of it, this is actually good. So it’s not surprising if these are the kind of preachers that you’re listening to that you find Calvinist YouTubers making bizarre claims like this.

CLIP:

I’m grateful for Judas because he was used in God’s divine plan. He was used in the sovereignty of God to redeem the elect. I want

Joe:

To be really clear, this is evil. To use another person as a means to an end without loving them as a person is objectification. Whether you’re looking at pornography or exploiting another person in a sweatshop or anything else, when you won’t treat the other person as a person, when you treat them as a mere means to your end, you’ve dehumanized them, and this is dehumanizing Judas, so they can proclaim how much they love. Judas Ray Comfort famously says Judas is his favorite apostle. That’s sick, that’s twisted, and this has both on the one hand, put Judas in the place of Christ and on the other treated both Judas and frankly, if you get into the theology, Jesus like mere objects to achieve the end of our salvation. So I want to suggest to the outset this is a bad way of doing it, but at the same time, I understand why someone reading the biblical evidence might come to this conclusion.

So we have to address the big problems like making sense of things like predestination. So I want to start with a simple question that’s not so simple. Does God cause evil? Because at the outset I know that there are going to be some of you already. If you haven’t jumped in the comments below making these kind of claims, you’re going to be like, well, God is the author of good and evil, and chances are there’s a tiny set of Bible verses you’re going to point to. One of the most common is Isaiah 45, verse seven, in which God declares I form the light and create darkness, and then as many translations have it, I make peace and create evil. Now, what you should know there is the Hebrew word there. Raw also means misfortune. And so that’s why other translations like the RSV say, I make wheel and create.

Whoa. Now, I wish wheel was a word we understood, but it’s like the idea that both whether things are going really well or whether there’s trial and tribulation and everything else, God is still God. He’s sovereign over all of that. He’s not saying that God is the author of moral evil, but rather that whether things are going well or badly, God is still in control. Like Ecclesiastes seven says in verse 14 that in the day of prosperity be joyful and the day of adversity consider God has made the one as well as the other so that a man may not find out anything that will be after Him, right? That God is still God, whether things are going really well or really poorly in your life. Now this makes sense of the actual context of Isaiah 45. Isaiah 45 isn’t saying, the God we thought was all good is actually all good and all evil.

He’s the author of both. No. The context of Isaiah 45 is that it’s during the Babylonian captivity and in the face of this challenge that Aha, the Babylonians won, therefore their gods are better than the God of Israel. Isaiah is prophetically responding that no, the exile was actually the result of God’s repeated threats. He said, if you keep acting this way, you’ll be punished and then they’re punished. This wasn’t showing that God was inferior to the Babylonian Gods rather God is someone who has the power to create the darkness and the evil of exile, not again, a moral that God is not doing something morally evil, but he’s allowing people to suffer trial and tribulation for their own good as he told them he would. So that’s one of the passages you regularly hear. The other one is about the hardening of Pharaoh’s heart. Now, I was actually asked about this recently a week ago on Catholic Answers Lives. I want to play you the question and then answer it

CLIP:

Need start Bible study pretty soon, and we’re going to go through Exodus and one of the things is God saying, I will harden Pharaoh’s heart, so I want to know about that.

Joe:

So who did harden Pharaoh’s heart? Exodus gives us three ways of answering that question. One way of just putting it in the passive voice, Pharaoh’s heart was hardened. You get that in places like Exodus seven, verse 13 and 22, Pharaoh’s heart remained hardened. That doesn’t tell us authorship just tells us what happened. Other times it says God hardened Pharaoh’s heart. For instance, in Exodus nine verse 12, the Lord hardened the heart of Pharaoh. It seems very clear, but then there’s a third way where it says Pharaoh hardened his own heart like Exodus eight in verse 32, but Pharaoh hardened his heart this time also, and so what’s going on here? Why does Exodus, I mean presumably the same author is using these three different ways of describing the hardening of the heart of Pharaoh. In fact, if you want to see a really fascinating bit, look at the end of Exodus nine and beginning of Exodus 10.

Now, remember, the chapter divisions aren’t original, so we’re just going to look at four verses in a row. This is at the end of the seventh plague and the beginning of the eighth plague, and the first thing you see is in Exodus nine, verse 34 we’re told that when Pharaoh saw that the rain and the hail and the thunder had ceased, he sinned yet again and hardened his heart, he and his servants. So Pharaoh and the servants of Pharaoh hardened their own heart. That’s what we’re told in verse 34. Verse 35 just says The heart of Pharaoh was hardened. That’s that kind of neutral passive expression. But then the next verse, which is the first verse of Exodus 10. In our Bibles, God says to Moses, I have hardened his heart and the heart of his servants. So in the course of three verses, really you have Pharaoh hardened his own heart.

Pharaoh’s heart was hardened, God hardened Pharaoh’s heart. How do we make sense of those three things? How can all three of those things be true? Well, for that, I want to turn to the 19th century extremely dapper Baptist preacher, Charles Spurgeon who said, I use this example all the time, but I want to give credit where it’s due. Spurgeon says, the same sun which melts wax hardens clay and the same gospel which melts some persons to repentance, hardens others and their sin. In other words, we can talk about the sun melting wax and hardening clay, but it would be a mistake for a person who doesn’t understand the sun to say, aha, the sun is really cold to one and really warm to the other. Nope, that’s not how it works at all. The sun is exactly the same to both. How they respond is different, and so likewise, God is all loving to both of us.

How we respond can differ, and so in this case that actually makes total sense of the passages. For instance, in the passage we just looked at the end of Exodus nine, we’re told that Pharaoh saw that the rain in the hail and the thunder had ceased. Well, who did that? God did that. God acts and Pharaoh reacts. So whether you want to call this God hardening Pharaoh’s heart because it was God who acted by stopping the plague, or whether you want to call it Pharaoh hardening his own heart because Pharaoh’s response to God’s action was to be hardened in heart. Neither of those is wrong, but as long as we know when we say that God hardened Pharaoh’s heart, this is not saying God removed Pharaoh’s ability to choose Pharaoh is clearly choosing. He is clearly acting. He’s clearly hardening his own heart, but he’s doing this in response to things God is doing.

He doesn’t have to, but he chooses to in the same way that you can hear the message of the gospel and be totally turned off by it, and we could say both you were repulsed by Jesus’s teaching or Jesus’s teaching repulsed you, both of those would be accurate, but one of those is morally culpable. You were repulsed by Jesus’s teaching. The other one isn’t culpable. Jesus’s teaching repulsed you, Jesus’s teaching is not morally responsible for your reaction to it, but nevertheless, both ways make coherent sense. So when we talk about God hardening Pharaoh’s heart, Pharaoh hardening his own heart, you need to understand this Old Testament mode of expression. Now, I would actually love to hear your comments below if you’ve encountered verses like this. If there are other verses, you want me to address that kind of look like this? Because this is one of the most common misconceptions that God is morally responsible for evil, and if you get that wrong, you’re not just getting the Bible wrong, you’re getting God wrong in a really big way.

Let’s apply that now to Judas. Was Judas predestined for evil? This is going to get into a big distinction about what we mean by predestination. So again, remember that line in Acts four from the prayer of the early Christians about how those who betray Christ, and we can add Judas here, they do whatever thy hand God’s hand and God’s plan had predestined to take place that God’s plan of salvation incorporated the evil deeds that the others would do. Herod punches Pilate, the Gentile and Jewish leaders, and we can add to this Judas, when we talk about predestination or divine foreknowledge, we often have three different ideas of what that means that are maybe muddled together. So I’m not call out all three of them and then show you that they’re different. The first possible thing that could mean is simply God sees everything that has happened is happening or will happen straightforward, right?

God foreknows, he knows what’s going to happen. He knows the future. It’s not future to him. Second, God not only sees but permits, everything that has happened is happening or will happen so far these two should both be fairly uncontroversial and I’ll explain why, but then the controversial one is number three, that God doesn’t just see everything that’s going to happen has happened, will happen. He doesn’t just permit it, but he actually decrees or desires it. He authors it in some way that God decrees or desires. Everything that has happened is happening or will happen. Now, some people hearing this are going to say, look, this is a distinction without a difference. If one of those is true, all three are true, and I want to say that is logically wrong, that is invalid and we can see why it’s invalid. So if you’re going to be patient with me for a second, I need to go through the deep waters of predestination slightly.

I know that can be something where your eyes glaze over and your head spins, but we need to work through it somewhat or we can’t make sense of basic things like why Judas is even in the picture. But the first thing I want to say is the fact that one of these is true doesn’t mean the other two are. These are distinct logically. The first one, God sees everything including future events. The fact that God sees it doesn’t mean he permits it and it doesn’t mean he decrees or desires it. A good way to see that would be something like if you’re familiar with Greek mythology, the figure of Cassandra, Cassandra is cursed with the gift of prophecy, but prophecy nobody listens to. So she always knows what’s going to happen in the future, but everybody ignores her. She sees what’s going to happen, but she doesn’t permit it.

She actively tries to stop it but can’t. Being able to see the future is an aspect of omniscience being able to know everything. That’s the first sense of foreknowledge or predestination. But God isn’t only omniscient, he’s also omnipotent, meaning he doesn’t just know everything. He’s also all powerful and so therefore everything that happens, he has at least permitted it to happen. Now, some things he clearly wants to happen. He’s very clear about this, but there are other things that happen that he seemingly doesn’t want to have happen, things like sin, and yet because he’s omnipotent, he could act in such a way as to prevent it from happening. He could make every evil doer immediately drop dead the minute they started to sin. He could do that. And so in some sense we can say God must permit not just see all the events both of the past, the present and the future, good events and bad events.

He sees them and in some way permits them to happen. Doesn’t mean he wants them to happen, he permits them to happen. Now, some people hearing that are going to say, well, obviously if he’s permitting it, that’s equivalent to decreeing or desiring it, that the second and third thing, if two is true, then three is true and that’s a mistake. And here I’d give you the example of something like a sting operation. This could be anything from the small cop running radar to catch speeders to something like an undercover operation to catch a criminal enterprise. In those cases, the police will permit an evil to happen. They’ll permit you to speed. They could have stopped it. They could have put a speed bump. They could have put a warning speed trap ahead sign. They could have encouraged people to flash their lights to get everybody to slow down.

They could have gotten all of evil doers, speeders or major criminal enterprise or whatever it is in between. They could have gotten them to stop, but they didn’t. They permitted the evil. Why did they permit the evil though? Well, so they could catch the evil doers in that case, so they permitted it not because they want crime to happen, not because they really want you to speed, but precisely that they can root out evil in a different way. So you can hate evil and still permit some measure of evil. We see this in human affairs. We see this in human society and so clearly that could be true of God as well. And this is how Christians have historically understood the problem of evil. The catechism of the Catholic church in paragraph 600 points out that to God, all moments of time are present in their immediacy.

There’s no such thing as future to God. So it isn’t even really that God is foretelling the future, it’s that future isn’t future to him. So he has an eternal plan of predestination, which the catechism points out includes each person’s free response to his grace. That is his plan of predestination includes how you will respond but not in a way that forces you to respond, not in a way that takes away your free will and not in a way where he’s decreed every response, both good and bad. How can we say this? Well, for the sake of accomplishing his plan of salvation, God permitted the acts that flowed from the blindness of the wicked, and so he remembered that line in Acts four. Now, we might still ask, well, why then? Okay, it makes sense for the speed trap makes sense for the sting operation.

Why does this make sense for God? Well, part of that answer going to be mysterious, and I want to just flag that at the outset that no Christian can stand and say Here is exactly why God permits every evil that happens. If the book of Job has taught us anything, it’s that it is fool heart to try to do that. Nevertheless, we can give a few theological principles. Joseph in the Old Testament gives the best version of this when his brothers, he’s reunited with them and they’re talking about the fact that they betrayed him. Joseph says to them, and as for you, you meant evil against me, but God meant it for good to bring it about that many people should be kept alive as they are today. The parallels to Judas there I think are actually kind of striking. Joseph is betrayed not by friends, but by his brothers.

But nevertheless, God permits, even though it’s not good, God’s not happy with it. He’s not saying hooray, they’ve betrayed their brother, thought about killing him and then sold him into slavery. But God uses this betrayal in a plan to save the Israelites from starvation and to save the Egyptians as well, that both the Jews and the Gentiles to use anachronistic terms are saved because God makes use of this act of betrayal. But nevertheless, we cannot lose sight of the fact God does not will the evil. He wills good from it. So paragraph four 12 of the catechism puts it in more technical language that God in his almighty providence can bring a good from the consequences of an evil, even a moral evil caused by his creatures that maybe you’re totally wrong by someone else, but in reflecting on that experience, you grow morally well.

God doesn’t want you to get hurt. That’s not his point. But if getting hurt causes you to grow, well he does want that and so he’ll permit you to get hurt. A good teacher doesn’t just immediately correct, oh no, my student’s about to make a mistake. I need to stop them. Before they do that, the teacher is powerful enough to do that. They can say, Hey, don’t answer that. That’s the wrong answer. And they could stop any real growth in their students by keeping them from making any mistakes. And we live in a society that frankly sometimes tries to do that, tries to keep people from making mistakes and in a way stops them from growing. God doesn’t do that. He permits us a great number of mistakes and sins and evils, not because he’s indifferent, not because he’s apathetic, not because he is not loving, but precisely the opposite because he wants to draw good from these situations, even the bad ones.

Paragraph four 12 goes on to mention the greatest moral evil ever committed. This is what Judas is wrapped up in the rejection and murder of God’s own son caused by the sins of all men. God doesn’t will that moral evil. If he did, he would be a sinner. Someone who desires moral evil is by definition a sinner, but God by his grace that abounds all the mor when sinner bounds as Romans five 20 says, brought the greatest of goods from this greatest of evils, the glorification of Christ in our redemption, and then the catechism stresses, but for all that evil never becomes a good, and here I would point to St. Paul. So St. Paul’s says pretty famously in Romans five 20 where Sinna bounds, grace of bounds, all the more, but earlier in Romans, he warns against misunderstanding that he says, if through my falsehood, God’s truthfulness abounds to his glory, why am I still being condemned as a sinner?

Right? This is a gospel of Judas problem that God can draw a good from my evil, but I’m still going to be punished for it. Well, yes. And he says, well, why not do evil? That good may come as some people slander charge us the same, but then he just says their condemnation is just sin is still sin. Even if God can draw something good from it, the fact that maybe somebody else’s crime may help you bust a criminal ring doesn’t mean what they did wasn’t a crime. So that I think is why we can say God, seeing everything being all powerful nevertheless permits evil. So far, I think Protestants and Catholics are largely going to agree. Where we’re going to disagree comes to this third realm where God decrees or desires or authors or wills the evil that isn’t true. So the first two senses of predestination God sees and permits are true both good and evil.

The third sense of God decreeing or desiring is true of good actions. God really does author salvation. He really does cause salvation, but he doesn’t author damnation. He doesn’t author moral evil and scripture never once says that he does. He might be responsible for our misfortune sometimes, but even what appears to be misfortune, God works all things to the good for those who love him. Even our misfortune isn’t really misfortune because God wills to draw good from that. He never authors moral evil. How can we say that? Well, one way is because it’s logically contradictory. There’s never a simple definition of sin the way Miriam Websters might do in the Bible, but about the closest we get is in one John chapter three, verse four, where he says, everyone who commits sin is guilty of lawlessness. Sin is lawlessness. Sin is a violation of the law of God, therefore it’s a violation of the will of God.

So to say that God authors sin is to say that God decrees that you violate his decrees, that he issues a law, that you violate his law, that God’s law is lawlessness, that is internally in coherent. It’s not just that a God who does that isn’t good, although this is also true. Instead, a God who does that isn’t even coherent as a sovereign, A sovereign who wills to undermine his own sovereignty would be like a king waging a civil war against himself. It’s nonsensical, and so it isn’t just that that’s a bad view of God, it’s that that’s actually an illogical view of God. Moreover, we praise God precisely because he’s good. Well, not just because he’s powerful, the devil is more powerful than us. We don’t worship the devil or praise him. We praise the Lord. For the Lord is good as Psalm 1 35 says, and so if God is the author of evil, it doesn’t mean anything to call him good, someone who does good and evil is not what we mean by all good.

God is all good. This is why we praise him. He is not just good in the sense of having this as an attribute. He is good as definitionally being good. He’s infinite goodness. More than that, he’s infinite love. God is love, not just loving love that’s not consistent with God being an evil to her, which is what someone who authors evil is. Third, the epistle of James first chapter verses 13 to 14 we’re told, let no one say when he is tempted, I’m tempted by God. For God cannot be tempted with evil and he himself tempts no one. Now remember, the vision of Judas is that he’s just a trigger who wasn’t just tempted by God but actually had no free will. God overwhelms him and then forces him to do evil that is completely 180 degrees opposed to the theology of James one. One of those two things is wrong, and I would suggest the Bible is right and the Protestant preachers are wrong.

So let’s take all of that theology and apply it now to Acts four when the early Christians are praising God and saying that these people who’ve betrayed Christ are really part of this plan to do whatever thy hand and thy plan had predestined to take place. In the verses preceding that, they quote the Psalms, they quote Psalm two, the first two verses in which the psalmist says, why do the Gentiles rage or think of the original says, why do the nations rage? And the people’s imagined vain things, the kings of the earth set themselves an array and the rulers were gathered together against the Lord and against his anointed. So notice they’re acting, they’re real actors. They’re setting themselves in array, they’re gathering together. They’re plotting together against the Lord. They’re willing, in other words, and so we want to say emphatically, yes, Judas has free will.

He had the ability not to do the things that he did and he still did them. God knew he would do them. God’s plan of salvation incorporated the fact that Judas would freely choose to do evil, but nevertheless, he wasn’t forced to do it. I want to be really clear. This is a weak analogy because you’re not omniscient and you’re not omnipotent, but if you think about something like a great football coach, say, Andy Reed, a good football coach is going to incorporate what they know the other side is likely do, and if they were omniscient and they knew perfectly what the other side was going to do, they could include those responses and make the perfect plan. They could say, okay, I know exactly what they’re going to do and our plan is going to use that to our advantage. That doesn’t mean that the other side wasn’t still free.

When I go back and rewatch an old game, it’s not that my ability to know how the game is going to end takes away the fact the players were free to do whatever they wanted in the moment. That’s not how that works. Knowing the future doesn’t take away the actor’s ability to act. Knowing the future does allow me to plan my action around it. If I knew the future, I don’t otherwise I’d probably play the stock market or something. Well, likewise, God knows everything, and so his plan of salvation includes how he knows the human actors he’s created or going to react. Now, it’s not just that he knows it. He’s permitted it to happen. He created us and he knows us inside and out better than we know ourselves, and he’s all powerful. He could snap us all out of existence or snap any of us out of existence if he wanted to.

He doesn’t do that. So it is more than the football coach. But notice that even the football coach knowing the future, there’s still free will, well likewise with God, even though he not only knows it but permits it, there is still free will and that includes Judas in Matthew 26 verse 24, Jesus says, the son of man goes as it is written of him. Now, I want to stop on that because that is clearly a predestination kind of reference. This is foretold by the scriptures God for knew that Jesus was going to die on the cross. Does that mean Jesus didn’t have free will? You’d better not say yes because if you say Jesus doesn’t have free will and Jesus is God, then your view of predestination has actually overwhelmed God, where God becomes subject to something like fate rather than being the author of everything, he is the predestinate.

He is the one who foreknows, and yet he can still speak of himself and say, the son of man goes. As it is written of him, he foretells what he is going to do in history. He’s still free, and if you think otherwise, please let us know. In the comms, I’d love to talk about this because that is a major theological error. So there’s this proclamation of the role of predestination in all of this, the role of divine foreknowledge in all of this. But then the very next words he says is, but woe to that man by whom the son of man is betrayed. Notice what’s involved there. Well free action. It’s not just woe to that man whose scripture foretold was going to go to hell for all eternity. I didn’t love him. No, there’s nothing about, I’m not really friends with Judas. I don’t really love Judas.

I don’t really want to die for Judas sins, any of that. None of that is there. All of that is only present in the minds of Calvinist preachers in scripture. The reason Jesus says it’d be better for Judas not to have been born is because he betrays Jesus. It’s not a betrayal. If you pull a trigger and the trigger does the only thing it can do, it’s a betrayal. If you count on someone and they don’t do the thing that they were expected to do and were desired to do and should have done and they don’t do it when D Fords lines up offside and costs the Chiefs a chance to go to the Super Bowl, that’s a betrayal. I don’t want to pick on D Ford and see what’s not good at lining up on sides. But the point there is you have an expectation that expectation is breached. If instead you expect, you say, Hey, the plan is line up offite, that’s not a betrayal. If the plan is turn me into the Romans, turn me into the high priest, that’s not a betrayal. Then you’re back in the gospel of Judas territory where it only looks like a betrayal and is actually part of God’s secret plan.

In John 19, there’s a really important part that I want to add to this because it can be easily missed. Jesus is before punches Pilate, Pilate says, do not know that I have the power to release you and the power to crucify you. And Jesus says something really fascinating in reply, he says, you would have no power over me unless it had been given you from above. So Pilate is only where he is because God and his sovereignty allowed Pilate to be there. Therefore, he who delivered me to you has the greater sin. What does that mean? That’s a pretty mysterious passage. I want to suggest a meaning to it. Pilate did not choose to be in this situation. In fact, we’re told Matthew 27, Pilate tries to even let Jesus go, but then when he sees that his words are having no effect and that a riot is forming, he washes his hands and says, I’m innocent of this righteous man’s blood.

See to it yourselves. He goes along with it, but he knew this was a bad plan, didn’t want to be involved in this plan, meaning this is not to excuse everything Pilate does. He does something evil here, but he does something evil here in a complicated situation in which he didn’t feel totally free. Jesus doesn’t say This isn’t bad, this isn’t evil. He doesn’t say that, but he does say that it’s less evil than the person who does choose to be there. Meaning Pilate is forced into a situation where he has to make a moral choice and he makes an evil choice that is still less bad than a person who deliberately puts themselves in a situation to make an evil choice like Judas. This is why Jesus can say he has the worst sin as the betrayer. But Jesus’ response to Pilate, I would suggest only makes sense if Judas has free will. If Judas has no free will, why is he held to a higher moral standard than pilot is? Why is he being judged more Culpably?

The last dimension that I want to explore at the outset might seem a little unrelated, but I think it’s important we last two dimensions, I should say. First I want to look at the idea that Jesus and Judas were friends. If you listen to John MacArthur’s vision, it sounds like Jesus is just pretending to be friends with him. He puts him in this kind of place of honor, but he’s really just using him. He’s manipulating him to bring about the plan of salvation. Then he is going to discard him and send him to hell. And in fact, there’s this strange phenomenon where a certain type of Protestant has to claim that Judas and Jesus were never really friends because they can’t accept theologically the idea that somebody could, for instance, be a Christian and lose their salvation. So everyone who goes to hell and it doesn’t look good for Judas, that everyone who goes to hell must never have been a true believer in the first place, must never have really followed Jesus in the first place, must never certainly have been friends with Jesus in the first place. So for instance, here’s the Protestant ministry, got questions answering the question about Judas.

CLIP:

Judas not only lacked faith in Christ, but he also had little or no personal relationship with Jesus. When the synoptic gospels list the 12, they’re always listed in the same general order with slight variations. The general order is believed to indicate the relative closeness of the personal relationships with Jesus, despite the variations Peter and the brothers, James and John are always listed first, which is consistent with their relationship with Jesus. Judas is always listed last, which may indicate his relative lack of personal relationship with

Joe:

Christ. I want to stress here that is not true. I mean it’s true. Judas is always at the end of the list of apostles. Peter is always at the beginning, and then James and John in some order and or James and John in some order are always in second, third, fourth place after Peter, the chief of the apostles. But this is about places of honor and dishonor. This is showing something much more about the authority structure of the church and not one’s personal relationship with Jesus. And in any case, even if he is 12 out of 12, does that mean he doesn’t have any friendship with Jesus at all? What about number 11? What about number 10? Did those people do we say they’re not real friends of Jesus, even though they’re apostles, it doesn’t really follow. So I’d say yes. First of all, Jesus and Judas actually were friends.

And moreover, let’s be really clear, Jesus wants Judas in heaven. It’s not true that Jesus just creates Judas to throw away in damned hell for all eternity. We can say this in two ways. Number one, from a broad theological perspective, because in one Timothy two, we’re told to pray for everybody because this is good and acceptable in the sight of God, our savior, who desires all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth. But number two, we can say this particularly about the friendship Jesus has with Judas, and I would suggest we see this first in a couple of Psalms that have historically been applied to Judas. These are Psalms of betrayal by a friend. The first of them is Psalm 41. In Psalm 41 verse nine, king David says, even my bosom friend and whom I trusted who ate of my bread has lifted his heel against me.

Now at the surface level, this is about David’s betrayal, one of his close confidants during Absalom’s rebellion. But in fact, this is much deeper. Jesus himself applies this psalm in which it speaks of a bosom friend betraying the psalmist. Jesus applies this to himself In talking about how the betrayal is going to happen, he says, I know whom I have chosen, meaning the other apostles, it is that the scripture may be fulfilled. He who ate my bread has lifted his heel against me. So he’s applying Psalm 41 explicitly to his own situation, to the situation of Judas. The Psalm 41 is about a friend betraying Jesus or a friend betraying the psalmist, I should say. And then we see this friend eating the morsel. This is the part John MacArthur was preaching on, that he gives the morsel to Judas and he receives it and eats it.

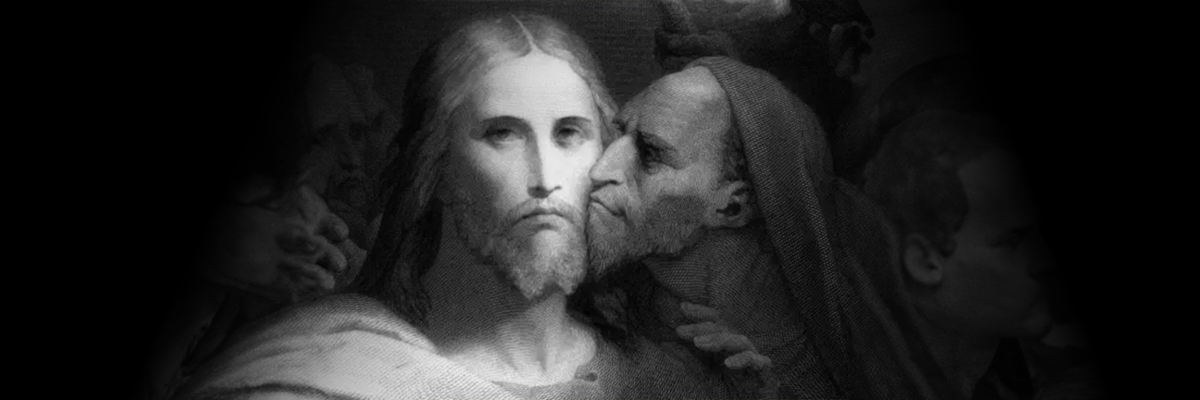

This was an act of one friend to another, and that second one betrayed the first friend. If you miss this, if you miss this is a betrayal of the friendship, then you don’t understand the relationship of Judas and Jesus. The other prophetic Psalm is Psalm 55, and this one is maybe even more striking King David again. He says, it is not an enemy who taunts me than it could bear it. It’s not an adversary who deals insulin lee with me. Then I could hide from him, but it is you my equal, my companion, my familiar friend. We used to hold sweet converse together within God’s house. We walked in fellowship. That’s a really striking kind of passage, and Christians were very quick to point out, this appears to be about much more than David. This appears to be about Jesus. So Jerome, for instance, talks about how to Judas these words were once said, but I would suggest that all of this is even more clear when you look at the betrayal of Jesus in Matthew 26, Judas comes up to Jesus in the garden of Gethsemane and says, hail master and kisses him.

Now he kisses him on the cheek. Now, this is significant because it shows it’s a sign of friendship. It’s not the way a servant kisses the master. You would kiss his feet or his hands. He kisses him on the cheek like an equal, like a companion. And Jesus doesn’t rebuke him for that. He doesn’t say, how dare you have the audacity to treat me like a friend? No, on the contrary, he says, friend, why are you here? Or in other versions do you betray the son of man with a kiss? But notice that he refers to him here as a friend. So I would suggest he really is friends with Judas. Now, why does that matter? Well, because you can’t say he just doesn’t care about his salvation and he’s his friend because the Calvinist view is that the reason Judas is apparently the son of perdition is because Keith’s not given the grace of redemption.

I want to be even more clear. The idea that Judas chooses to go to hell makes sense. It doesn’t make sense to say this had to happen. Meaning even if you say Judas, betrayal had to happen for Jesus to save the world, which isn’t true, God uses Judas betrayal, but to suggest this was the only way it could happen is naively narrow-minded, the idea that God could not have found another way for Jesus to die on the cross or another way to bring salvation in the world, other than this one particular one seems obviously absurd, but even if you believe that it doesn’t follow that Judas has to go to hell. So for that final point, let’s consider the betrayals of Judas and Peter because it’s not just Judas that betrays Jesus. It’s also Peter. Jesus says at the Last Supper that Peter will deny him three times, and sure enough, he does that.

Now, what’s striking there is denial is immortal sin denying Christ. Jesus says very clearly, everyone who acknowledges me before men, I also will acknowledge before my father in heaven. But whoever denies me before men, I also will deny before my father who’s in heaven. So one of the reasons these Protestants go to such length to say, Judas must never have really been a Christian. He must not really have been, even though he is one of the 12, he couldn’t really be part of the church. He couldn’t really be a follower of Christ, couldn’t really be his friend, certainly is because they don’t like the idea that you can lose your salvation. But here we see Peter doing something that if Jesus is to be believed, costs your salvation. If you deny Christ before men, Jesus promises to deny you before the Father. Peter has now three times denied Jesus before men.

But fortunately that’s not the end of the story. After he does this three times, Jesus turns and looks at him and Peter struck to the heart. He remembers Jesus’ words about how he’s going to deny him three times, and we’re told in Luke 2261 to 62 that he went out and wept bitterly. That is he had a genuine remorse for his sins, didn’t want to live that life anymore. And when given an opportunity after the resurrection, he proclaims three times that he loves our Lord. Jesus asks him three times, do you love me? And he says, yes, Lord, you know that I love you three times showing this kind of public contrition for the threefold denial. So what separates Judas and Peter isn’t that one betrayed Christ the other didn’t. Arguably they both betrayed Christ. Peter just did it three times because the denial seems like a form of betrayal.

What’s different is how they react to it. Peter reacts with repentance and love. Judas has a kind of repentance. Matthew 27 we’re told when Judas, his betrayer, saw that he, Jesus was condemned, he repented and brought back the 30 pieces of silver and says, I have sinned and betrayed innocent blood. The chief priests and the elders then say, when is that to us? See to it yourself. Horrifying, horrifying indifference to Judas Soul and Judas Despairs at that point, he throws down the piece of silver in the temple and then he goes and he hangs himself. What’s different between Peter and Judas isn’t that one sin and the other one didn’t, or that one sin was really bad and the other one wasn’t. They both did really horrible things to Jesus. It’s not even on the level of just a natural remorse. They both have that.

The difference comes next one turns to Jesus in love. One turns inward into despair and suicide. That’s where the difference is. This is why we don’t remember St. Judas the Apostle in some glorious noble sort of way. But again, I want to stress here. This is not because God didn’t love Judas. He loves him. He treats him as a friend. All that’s to say, it strikes me that it makes much more sense from a vision of free will to say Judas is created by God because Jesus loves him just like he creates all of us. There’s something mysterious about the fact that he loves us, even though he knows we’re going to betray him, even though he knows we may not spend eternity with him by our own free choice. That answer, as unsatisfying as that might be, I would suggest it’s still superior to the answer that God just predestined Judas to hell and therefore isn’t a true friend to him, even though Judas damnation is in no way necessary for the plan of salvation, right?

If Judas had turned back and repented, Jesus would’ve still died on the cross. It was not necessary, and yet still seemingly happens. We’re not told that explicitly, but we’re given what appear to be clues that it’s better for him not to have been born. He’s a son of perdition. St. Peter has some pretty bad things to say about him in Acts one, applying the Psalms to him about let his habitation be destroyed and let another take his office. So what can we say at the end of this? I want to recognize that even given this, seeing the bad views of Judas and laying out a little bit of a sketch of a better view, I think we should be left a little dissatisfied, meaning we don’t have the full answer yet and maybe won’t ever have the full answer this side of eternity. We can say a few things though.

We cannot say exactly who or how many people are damned. That’s not given to us. We cannot say that some people go to hell. We do not know what kind of divine graces they were offered during their lifetime. We don’t know all of the ways that Jesus reached out to Judas, both the exterior ones that we see and the interior ones that we don’t see. We don’t know the extent of that. We do know that God desires everyone, including you, including Judas to be saved. And we do know that God’s mercy is infinitely larger than the worst sin of human history. The betrayal and what’s more God’s mercy is infinitely larger than the worst sin you’ve ever committed. And I say this, so this isn’t just a theoretical exercise or just an idle curiosity about Judas that we should take from this, that we can be Judas or we can be like Peter. All of us have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God, and all of us have to decide given that, how are we going to respond to that? Are we going to trudge on in pride? Are we going to fall into despair and say, my sins are bigger than the mercy of God, or are we going to throw ourselves into the open arms of our savior, realizing he loves us, wants to heal us and make us holy

For Shameless Popery; I’m Joe Heschmeyer. God bless you.