Audio only:

Joe Heschmeyer examines Simulation Theory, its coherence, and what it reveals about materialistic atheism.

Transcription:

Joe:

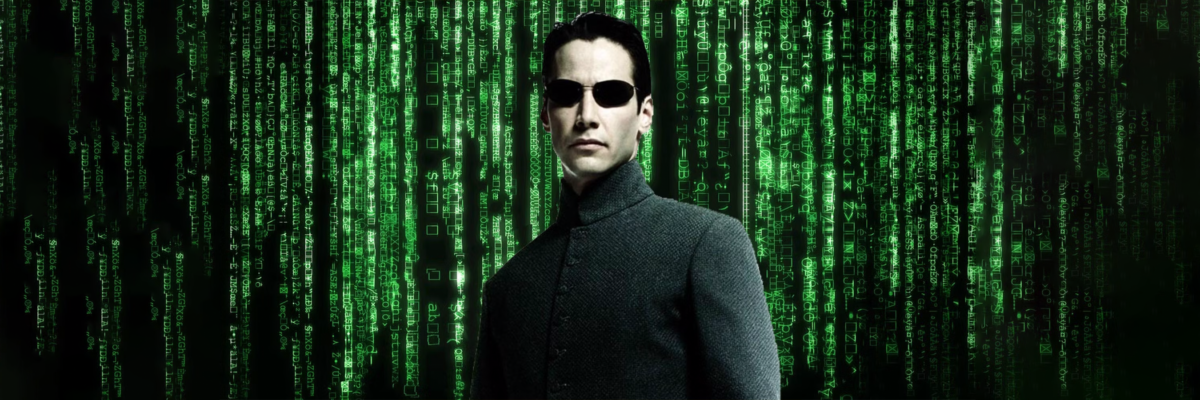

Welcome back to Jamus Pore. I’m Joe Hess Meyer. I don’t know why there aren’t more people talking about the fact that right now some of the smartest, most influential and wealthiest people on earth literally don’t think that we’re alive right now. I’m referring of course to the theory that we’re all living in a simulation now, for many of us, that theory, this idea that we don’t exist, it seems self evidently silly. If we’ve thought about the idea at all, chances are it’s just been in the realm of fiction

CLIP:

Right now. We’re inside a computer program. Is it really so hard to believe implants? Those aren’t your memories. They’re somebody else’s. It exists now only as part of a neural interactive simulation that we call the Matrix. You’ve been living in the dream world neo,

Joe:

But in reality, the sort of simulation theory being propagated today goes even further than the kind of things we might’ve seen from movies like Blade Runner, the Matrix, because in Blade Runner, the replicants don’t know that they’re not real. They’re just robots, but they’re operating in the real world in the Matrix. Neo’s living in a simulation, but he still has a real body out there in the real world. It’s more like the state of somebody dreaming. But what Joe Rogan, Elon Musk, Neil deGrasse Tyson, and so many other people today are arguing for is that you and I literally don’t exist. We have no bodies in any reality. We are just delusional computer code. So how have so many smart people ended up here? Well, of all things, it seems to have started with a fight about the soul. So I want to make three arguments in this video. The first is if the soul doesn’t exist, then we probably do live in a simulation. Now, I know that sounds kind of crazy, so let’s unpack that a little bit at a time. First, I want to actually start with the argument against the soul. Now, this is going to be from Neil deGrasse Tyson, and I think it’s pretty characteristic of what we might call the materialist or physicalist case against the soul.

CLIP:

Who are you? Is there something in you that lives independent of your physical existence? That would be the soul, what a soul would be? Alright, alright. What I do know is everything you are derives from electrochemical synapses running in your brain. This is a great triumph for our understanding of physiology.

Joe:

So as it’s often presented, this is kind of the triumph of cold heart science over the delusional idea of souls and the immaterial. But you’ll notice, and this is a really critical argument, the claim here is that you are just synapses. Every part of you are just these physical, observable material realities. So this view of reality is sometimes called materialism, not in the sense of being greedy, but in the sense that it believes that matter is all there is. It’s also sometimes called physicalism all probably use both terms for it, but they mean the same thing here. So here’s a nice short summary, but it’s basically the argument. We are living in a material world and we are material people.

CLIP:

Materialism is the view that nothing but physical matter exists to a materialist. There’s no such thing as a supernatural and nothing can be that is not comprised of physical components. Materialism is a metaphysical stance in that it denies metaphysics altogether as there can be nothing beyond physics when the physical is all that there is. This position obviously denies the existence of any God or of a soul. This position claims that there can be no immaterial component to the mind as well.

Joe:

So not all atheists are materialists in this sense, but virtually all materialists are atheists for the reason you just heard. If you don’t believe in a spiritual or immaterial realm, then it’s hard to square that with the existence of God unless your image of God is of a physical being. I have no idea of exact numbers here, but I do know that the philosophers, David Borer and David Chalmers surveyed hundreds of their peers and found that about two thirds of the philosophers that they surveyed self described as atheists and slightly more than half of them reported being physicalist or materialists. So if you do that math and you assume that all of the ISTs are also atheists, then it looks like about three quarters of atheist philosophers are also physicalist. I don’t know what the general public numbers would be. I don’t even know where to begin in looking for that, but on an anecdotal level, it’s pretty widespread.

A lot of the reasons people don’t believe in God or angels or souls or anything like this is because they believe in materialism, and this is very much the intellectual air that we believe. It’s this idea that if something is real, it must be observable, it must be testable, it must be accessible to the senses. Right now, there’s a lot of philosophical arguments you can make against this position. It is a metaphysical position against metaphysics as you just heard, but I’m not going to explore any of that philosophical route at all. Instead, I want to focus on something else because here’s the catch physicalism materialism. It makes sense on one level, but the problem is if materialism is true, then we should be able to artificially create consciousness. Think about it like this. If consciousness or sins, the mind, the soul, whatever you want to call the subjective experience of reality, if that is just synapses, as Neil deGrasse Tyson says, if it’s just some kind of material state, if it’s the mere arrangement of atoms, then why can’t we artificially arrange atoms in that way?

Why can’t we start with non-living things and then take their atoms and put them in such a way that they become living things that are not just alive, but even self-aware? If self-awareness is just the arrangement of atoms or synapses or fill in the blank, the arrangement of physical parts or particles, then why can’t we put them in that arrangement? This is a serious question being posed largely by people who think we’re just not there yet. In the world of artificial intelligence, this is what’s called machine consciousness, and you’ve got AI companies who are actively claiming that we’re going to get there in the next stage of AI development. We’ve had machine learning, now they claim we’re about machine intelligence and we’re going to get to machine consciousness. That’s that kind of that kind of idea. So again, you might say, okay, maybe that’s the right answer, right?

We can’t do it right now, but we’re just around the corner from it. Or maybe we’re not around the corner, but somewhere down the road people will be able to do that. Some super advanced civilization. Well, if you buy that, you’ve got a problem. Enter Nick Bostrom. He’s a philosopher at Oxford University and back in 2003, so well before we were having these conversations at the broad societal level, he wrote this massively influential paper asking a really simple question, are you living in a computer simulation? Now, his argument is actually really simple. If materialists like Neil deGrasse Tyson are right, that consciousness is just a physical state, and if every year we’re getting closer and closer to having the technological capabilities to create machine consciousness, well then someday we’re going to seemingly arrive at the point where we can create billions of simulated people who think that they’re real as Boston puts it, because their computers would be so powerful.

Future generations could run a great mini such simulations. Suppose that these simulated people are conscious as they would be if the simulations were sufficiently fine grain and if a certain quite widely accepted position in the philosophy of mind is correct. Now that quite widely accepted position, the philosophy of mind is physicalism saying, if you accept physicalism, then in which he does, by the way, he’s not intending this as a critique of physicalism, although I think ironically it is. He’s saying, okay, if physicalism turns out to be true, then we’re going to get to a situation where one of three things happens. This is a trimmer that he lays out. Number one, the human species is very likely to go extinct before we reach the ability to be able to do so. Whether we’re just around the corner or whether it’s a little further down the road, we’d have to say there’s going to be some civilization ending event that the reason future civilizations won’t ever create.

This isn’t because it’s technologically impossible. It’s because before we get there, we’re going to destroy ourselves or be destroyed. That’s one possibility. The second possibility is that we basically just get bored. We decide that even though we can do it, we could create all these simulations. We could create artificial machine consciousness. We just decide not to. Maybe we’ve got an ethical qualm against it. Maybe we’re just so distracted with sports or who knows. Option two I think is the least plausible, which then leaves us with option three. If you don’t have a civilization ending event that ends all civilizations capable of doing this, and if you don’t have, we just decided we were too good for this, then you’re left with the fact that we have civilizations that someday can and will want to create artificial consciousness, and so therefore they will. That’s going to lead us in option three with his claim that we are almost certainly living in a computer simulation.

They might be saying, hold on. How does it follow that if we can and will create simulations that create consciousness in this way that therefore we’re probably living in one of those simulations right now? Well, the argument is really simple. He says, in this world it could be the case that the vast majority of minds like ours do not belong to the original race, what’s sometimes called base reality, but rather to people simulated by the advanced descendants of an original race. It is then impossible to argue that if this were the case, we would be rational to think that we are likely among the simulated minds rather than among the original biological ones. Now that sounds confusing and so let me break it down the best I can. If Bostrom is right and I think he is here, physicalism means someday we’ll be able to create everything that makes up human consciousness.

Everything that previously been thought of as a human soul, you can make that in the system, and so the fact that you are conscious, the fact that you think you have a soul, that you have a mind, that you have self-awareness and all of that doesn’t prove that you are real. It could mean that you’re a simulation and what’s more, well, the numbers game just works heavily against you. If you’ve ever played something like the Sims or any kind of computer game, you know can create an entire world with hundreds of different creatures in them, and that’s just in an afternoon, it might look like years and years to their life, but for you, that’s just an afternoon and then maybe later in the evening you start the game over and play a different set. So if you think about the number of characters you’ve created or played as compared to the number of you, there are just the one, the ratio is wild, and that’s what’s current technology.

So you can imagine the kind of civilization capable of creating computer programs where the characters are self-aware and think they’re alive. They could be creating billions of these at the snap of a finger, and so the odds that we are living in the base reality seems extremely unlikely. Well, it’s more than that. The usual response here is, well, we don’t have the technology for that, but that doesn’t matter. I mean, you can imagine a world in which you play right now. You can play a game where you’re somewhere in the past where they don’t have computers. Okay, that’s fine. That doesn’t prove that computers don’t exist. So right now, the fact that we don’t have the kind of technology bostrom’s talking about doesn’t mean that technology doesn’t exist in a higher plane of reality. That’s the argument that if a future civilization could create artificial consciousness within the world that they’re creating, you’re going to have people just like you and me who think that they exist, but are really just computer simulations.

And if those people could exist, well statistically, we are more likely to be them than we are to be the people who are in on the secret of reality. I almost want to use the analogy of something like a or a Ponzi scheme. If you realize, oh, well, this Ponzi scheme means that 10 times more people are going to be conned than are in on the scam, well, statistically, you’re probably getting conned then unless you have a really good reason to know you are not one of the marks, you’re probably one of the marks. Well, this is kind of that argument. If bostrom’s right, they’re way more fake people than real people, and all of them think they’re real. So the fact that you think you’re real doesn’t mean you’re real statistically, you’re more likely to be fake. So that’s the argument kind of in a nutshell, and I think if you grant physicalism materialism, it’s pretty logically airtight and strangely enough, a lot of prominent intelligent, well-respected people admit this. So for instance, Negras Tyson says this,

CLIP:

I wish I had a good argument against that hypothesis, and I do not,

Joe:

And he’s not alone. You remember the philosophy study I mentioned earlier with the two authors, one of the co-authors, David Chalmers, who’s well respected as a philosopher in his own right, also can’t find an argument against it.

CLIP:

It’s an idea that I do take seriously. I think maybe there’s a very significant possibility that all of this right now is simulated. I can’t say I know that it is, but I also can’t say I know that it’s not

Joe:

At a popular level. I’m fascinated by the way that people like Joe Rogan have seized upon this theory and both have it very seriously and helped to make it much more part of the mainstream conversation.

CLIP:

You’re in a simulation with artificial memories implanted into your mind. Well, the one day that the idea is that there’s going to be an artificial reality or a virtual reality that’s so good that it’s indistinguishable. I mean, this is almost inevitable. If technology increases the same rate that it’s increasing now, whether it’s 50 years from now or a hundred years from now, we’re going to reach some point in time. So the real question is when we do reach that, how will we know? Well, what if we’re already there? Yes, but if it is a simulation, how would we know and how

Joe:

Do we test

CLIP:

It? How do we test it?

Joe:

It’s also striking to me that the richest man in the world right now seems acutely concerned by the problem, and he tells a stunned crowd that he thinks is almost certain that we are in fact living in a simulation.

CLIP:

The strongest argument for us being in a simulation, probably being in a simulation, I think is the following. That 40 years ago we had pong like two rectangles and a dot. That was what games were. Now 40 years later, we have photo realistic 3D simulations with millions of people playing simultaneously, and it’s getting better every year and soon we’ll have virtual reality, augmented reality. If you assume any rate of improvement at all, then the games will become indistinguishable from reality, just indistinguishable, even if that rate of advancement drops by a thousand from what it is right now, then you just say, okay, well, let’s imagine it’s 10,000 years in the future, which is nothing in the evolutionary scale. So given that we’re clearly on a trajectory to have games that are indistinguishable from reality, and those games could be played on any set top box or on a PC or whatever, and they would probably be billions of such computers or set top boxes, it would seem to follow that the odds that we’re in base reality is one in billions.

Joe:

I want to make sure you got that point he’s making. He’s saying, if you assume any rate of technological improvement, and he doesn’t say this, but this is an important part of it, if you assume if you deny something like a soul, then you end up in a situation where as he says, the odds that you’re not in a simulation is one in billions, you’re almost definitely not real. He’s not saying, here’s a crazy idea that I was kicking around in college, or Wouldn’t this be kind of a fun sci-fi story? No, this is what he thinks is actual reality, and this is what a lot of other prominent people, scientists, philosophers, and sure podcasters think as well. I want to point out two things about that. Number one, I want to acknowledge that outcome is logical. If you start with physicalism and number two, that’s a disaster intellectually and logically, right?

If we can’t figure out if we’re alive, if we can’t figure out if reality exists, then we have to admit that we have basically no knowledge. You can say, maybe I think therefore I am, but you don’t even know if you are or if you’re just a simulation. So if you’re an atheist and you believe in materialism, this should be a red flag. If the reason you argue against God is because you deny the immaterial realm, you should be aware that your system of thought doesn’t just reject the existence of God. It also rejects the existence of you, but the argument gets even weirder because that’s just the logical implications of physicalism that it leads to it being more likely than not that you’re in some advanced civilizations computer game than that, you really exist. The second problem is, from an atheist perspective, it’s a problem.

I should say. The simulation arguments are design arguments. Now, hopefully that’s straightforward. If you believe that your reality is a simulation designed by somebody else, either a programmer in base reality, or maybe you’re a simulation created by a simulation, created by a simulation somewhere, then you believe that your reality is designed your entire universe, everything you’ve ever perceived is all the result of design. In fact, if you want to be provocative, you might say it’s even the result of intelligent design, some system or beings or being unimaginably more powerful than we are right now, created a world we can’t even fathom with an intelligence. We don’t come close to grasping. I don’t mean that to be a superficial point. I mean to point out the absurdity of atheists like Neil deGrasse Tyson, who on the one hand say things like this,

CLIP:

It’s hard to argue against the possibility that all of us are not just the creation of some kid in a parent’s basement programming up a world for their own entertainment,

Joe:

While at the same time having the goal to say things like this.

CLIP:

In my studies of the universe, I value evidence and I don’t see evidence for any kind of active intelligence or power over anything. But if you had that evidence, show it to me. I’m all

Joe:

In. So look, logically you cannot believe both that the universe we experience is a simulation designed by someone else and that the universe that we experience is not designed. You can’t simultaneously insist upon designed by a teenager in a garage and simultaneously claim you’ve never seen evidence of design. Those two things cannot both be true. Now, in Neil deGrasse Tyson’s defense, even though he’s basically an atheist, he does say he’s technically an agnostic. He’s open to the evidence. Well, I would suggest here is the evidence, the probability that our universe is designed is by definition higher than the probability that our universe is designed by a simulator, the teenager, computer programmer, whoever. And so if you buy the simulation argument that the odds are billions to one, that it wasn’t designed by a simulator, you have to say it’s a almost 100% chance that we live in a world designed by a simulator.

Then you have to say the argument for universal design is at least that high, plus you have whatever the probability is that we live in a universe designed by God or designed by some other kind of designer I haven’t even thought of. So once you recognize simulation theory is just a dorky form of creationism, then you realize, okay, you’re still believing in intelligent design. You’ve just replaced God with some guy in a garage, and you’re still ending up in a place where you say, yeah, the universe is designed. We can make a couple other points on this as well. Number one, you have to concede if you’re going to believe simulation theory that nothing in the universe is inconsistent with design. So sometimes atheists will argue the universe couldn’t be intelligently designed. Here’s this part of the universe I don’t understand, and it seems random or meaningless.

I don’t get why it is the way it is. Now, the usual response is there’s probably a good reason you just don’t understand it, but you can’t even make this argument as an atheist if you believe in simulation theory because if you believe in simulation theory, by definition, you believe it is designed. Number two, you also have to grant that the universe that we exist in appears to be designed by, it appears to be designed. I don’t mean that you look around and you say, oh, yes, this is obviously designed just from observation. What I mean is that the world that you observe is consistent with a designed world. This is kind of the inverse of the first one I made there. So when you’re looking at reality, you’re looking at what looks like a designed universe, even if it’s not the way you would’ve designed it, even if it’s not the way you would play the game or create the simulation or whatever, you have to grant that the reality that you live in appears to be designed and that there’s nothing in there obviously inconsistent with the possibility of design or else you’ve disproven the simulation theory.

If you say, aha, it can’t be a simulated reality because X feature is impossible with design. If you find that, then you’ve disproved simulation theory and seemingly disprove the existence of God. I don’t even know what that argument would be, but if you think you’ve found it, that would be an argument against simulation theory. But notice none of the people that we heard from before think such an argument exists, and I don’t even know what that argument would look like. So if you’re going to buy simulation theory, you can’t make that argument. You have to say nothing in the universe is inconsistent with design. Everything we observe is consistent with it. It appears to be designed, and here’s the kicker, you might say, yeah, yeah, that’s fine for this reality, this is one of the simulated realities. We are created by somebody in so-called base reality.

But yet, here’s the thing. The final thing you have to grant is that this is also seemingly true of base reality. Here’s why, at least in Bostrom’s formulation of it, what we’re living in is a simulation that is based on base reality. So if you think about it, when we make a computer game, there’s fanciful elements. It might be on a different planet, it might be in a different time period. It might be in a different kind of scenario, but there’s a base level to reality that stays pretty consistent. You would know something about the outside world just from looking at the kind of games that we play. You’d know something about human-like creatures. You’d know something about the existence of physics. You’d know certain attributes, even though it’s not a perfect simulation of the world in which we live, it is a sort of replication of it.

It’s a sort of replica of it, even if it has an intentional twist here or there. So base reality, assume for a second we’re in a simulation. Either number one, you say we aren’t. We live in base reality and it appears to be designed because remember the earlier two points, nothing in the universe that we observe is inconsistent with design. It all appears to be designed or we’re living in one of the simulated universes within this world, but we’re living in a simulation of base reality, and if in our simulated reality everything looks designed and it’s a copy, even if it is a copy with a twist of base reality, then everything we know of points to base reality being designed as well, which means that even if you buy the kind of, so the weird thing about this argument in other words, is that rejecting the soul, rejecting God because of a belief in material reality alone naturally leads to simulation theory.

Simulation theory naturally leads to belief that the universe is designed and not just the simulated realities in the universe, but also seemingly base reality itself, which gets you back to the very place you were trying not to end up, that there is a designer behind the universe, someone or something we might call God. Now if we’re in a computer, maybe we don’t owe a final allegiance to the God of the universe because we owe our allegiance to the computer programmer, but our God in that case has a God and it’s the one we’ve always been calling God. So that’s the idea. The simulation argument, even it starts from atheistic premises, but it ends with design conclusions, which I find pretty fascinating. But the third and final argument I want to make is that I think there’s a solution to the simulation problem because I think, as I say, I think Strom is right in saying this is where physicalism ends up. But I think this isn’t an argument that we’re living in a simulation. I think this is more effectively an argument that physicalism is obviously wrong. So I want to start with looking at BOLs m’s kind of deeper take because I’ve alluded to the fact that his argument is airtight. If you grant his views of physicalism and the views shared by many of the people we’ve heard from in today’s episode, but what are those views specifically? Here’s how Strom explains it in terms of creating consciousness.

CLIP:

If you had a computation that was identical to the computation in the human brain down to the level of neurons. So if you had a simulation with a hundred billion neurons connected in the same way to human brain, and you then roll that forward with the same kind of synaptic weights and so forth, you actually had the same behavior coming out of this as a human with that brain would have, then I think that would be conscious.

Joe:

I want to make sure that you understood the argument he was making because I think it’s an important argument and a pretty logical one. If consciousness is something like a piano say, then we should be able to replicate it. If it’s a physical object is a complicated physical object granted, but ultimately a physical object or a state of physical interactions between objects, we should be able to replicate it. And if we did that, we would by definition seemingly have consciousness. So think about it like this. If you took a Steinway piano and you copied it maybe down to the smallest atom, or honestly, I don’t know what the smallest conceivable part would be, but you do that, okay? You take it as much as you can atom by Adam and you copy it, your resulting copy would seemingly be a piano. Now, sure, we could have an interesting philosophical discussion, whether it’s a Steinway piano since it was made by you and not Steinway, but it’s atomically identical to a Steinway piano, and I don’t think people would have any problem saying, sure, that’s a piano.

The problem is this is where we are. If the mind is like that, if it’s just neurons in the brain or synapses or what have you, then BOLs Fromm iss, right? We should be able to go into the lab and duplicate it and make some copies, and if that’s true, then how do we know we aren’t the result of somebody already doing that? Or you should be able to go into the computer and make digital copies. That’s how we end up with the simulation argument. But what if the problem is that bolster is wrong, that Neil deGrasse Tyson is wrong, that all of the physicalist and materialists are just wrong? In other words, what the problem isn’t? We’re living in a simulation. What if the problem is consciousness isn’t a physical property or object like a piano in the first place? It has immaterial qualities.

It’s not reducible to matter. Well, if that’s true, then it makes sense that computers can act like they have consciousness, but they can’t ever really have consciousness. They can imitate it, but they can never embody it. Like a calculator isn’t actually doing math the way that a human is doing math. If someone asked you, what’s seven times six? You’ve got a mental process going in your head. The calculator’s not thinking and coming up with its best guess. It’s following a set of criteria, producing a result. So even if it can do math better than you can, in another sense, it can’t do math at all. Now, let me explain, actually better yet, let me have somebody else explain, because this is what’s called the Chinese Room experiment. This is a helpful way of understanding the difference between imitating intelligence and actual intelligence.

CLIP:

Can a machine ever be truly called intelligent American philosopher and Rhodes Scholar? John S certainly can. In 1980, he proposed the Chinese room thought experiment in order to challenge the concept of strong artificial intelligence and not because of some eighties design fad. He imagines himself in a room with boxes of Chinese characters he can’t understand, and a book of instructions, which he can. If a Chinese speaker outside the room passes in messages under the door, so can follow instructions from the book to select an appropriate response, the person on the other side would think they’re chatting with a Chinese speaker, just one who doesn’t get out much. But really it’s a confused philosopher. Now, according to Alan Turing, the father of computer science, if a computer program can convince a human, they’re communicating with another human, then it could be said to think the Chinese room suggests that. However, well you program a computer, it doesn’t understand Chinese. It only simulates that knowledge, which isn’t really int intelligence.

Joe:

The advantage of this theory that there is something immaterial like the soul to intelligence, is that it doesn’t just explain the failure of AI to create machine consciousness or that it can help us to curb our expectations. As companies have announced they’re going to spend tens of billions of dollars, even as much as a hundred billion dollars on a supercomputer to pursue AI research in the near future, it’s more than that. It’s that recognizing the falsity of physicalism actually helps to explain a much longer string of scientific failures of promises that have never really been delivered. What I mean by that is this, for literally hundreds of years now, scientists have been claiming to be on the verge of creating synthetic life. Synthetic life is creating a living thing from non-living parts. As a science writer, Philip Ball points out creating life from scratch is a dream as old as myth, but no one has done it.

And as our knowledge deepens, the problem seems ever harder. Spontaneous generation, the idea that life can materialize abruptly from inanimate matter was once considered a trivial, almost inevitable feat. Even in the 19th century, it was widely thought life might arise through chemical synthesis. It was just a matter of finding the right composition. But with today’s emphasis on information and organization and biology, the tasks seems gargantuan. So you’ll notice a couple things. One, even in that description, the door is not closed, and maybe someday they’ll be able to chemically create synthetic life. And this idea, which as ball says was very popular in the 19th century, is the background to stories like Frankenstein. The idea is scientists are going to be able to take non-living things and put ’em together in such a way that it creates life, and maybe that’s bad. This is a modern Prometheus.

As Mary Shelley puts it, Prometheus famously steals fire from the gods and creates this kind of catastrophe through a misuse of technology. So that’s the argument. So back then it was, okay, we’re going to be able to create synthetic life through chemistry. Now you’ve got people claiming that we’re going to be able to create synthetic life through digital technology. What you couldn’t do in the lab, maybe you can do in the computer, but the reality is neither side has ever come anywhere close to this. Sure, you can find Chinese room type experiments where you can have ai that sounds like it’s smart, but it becomes pretty clear over the course of time that it’s just aping intelligence rather than actually possessing it. It doesn’t have a sense of sentence, it doesn’t have a sense of self, and there’s no reason to believe that that’s going to change.

At any point in the future, if you think that it will, you seemingly have to grant the premises to the simulation argument. If the simulation argument is false, then you seemingly have to realize that there’s something wrong with the underlying premise of physicalism. So I’ll end by suggesting this first, if a group of people have been claiming for literally centuries now that they’re on the verge of delivering on a promise, in this case, the promise of synthetic life or artificial consciousness, and they still haven’t delivered for centuries, maybe you should be more skeptical. I don’t mean that AI doesn’t have any useful applications. It does, but I mean, the people who think, oh, it’s just around the corner, are like Charlie Brown going to kick the football time after time after time again, and a little more cynicism, a little more skepticism might serve you well. Second, if it turns out that scientists can’t create life and can’t create consciousness either in a lab or in a computer, the most obvious explanation is that it’s because the ingredients of life involves something more than atoms. Now, we haven’t gotten into a deep dive here as to what that something more is, but it has to be something in material. We aren’t just animated because of matter, but because of something else, something which we Christians call us soul.

I’m Joe Meyer. God bless you.