Episode 67: Year B – 3rd Sunday of Lent

In this episode of the Sunday Catholic Word, there are three details that we focus on. One comes from the first reading, taken from Exodus 20:1-17, which records God’s deliverance of the ten commandments. The related apologetical topic is having religious statues within our religious spaces. Another comes from the second reading, taken from 1 Corinthians 1:22-25, and it has to do with whether God approves of philosophical reasoning. Finally, the third detail comes from the Gospel reading, which is John’s report of Jesus’ overturning of the moneychanger tables in the temple, recorded in John 2:13-25.

Readings: Click Here

Looking for Sunday Catholic Word Merchandise? Look no further! Click Here

Hey everyone,

Welcome to The Sunday Catholic Word, a podcast where we reflect on the upcoming Sunday Mass readings and pick out the details that are relevant for explaining and defending our Catholic faith.

I’m Karlo Broussard, staff apologist and speaker for Catholic Answers, and the host for this podcast.

In this episode, there are three details that we’re going to focus on. One comes from the first reading, taken from Exodus 20:1-17, which records God’s deliverance of the ten commandments. The related apologetical topic is having religious statues within our religious spaces. Another comes from the second reading, taken from 1 Corinthians 1:22-25, and it has to do with whether God approves of philosophical reasoning. Finally, the third detail comes from the Gospel reading, which is John’s report of Jesus’ overturning of the moneychanger tables in the temple, recorded in his gospel 2:13-25. The related apologetical topic here is the historicity of John’s Gospel.

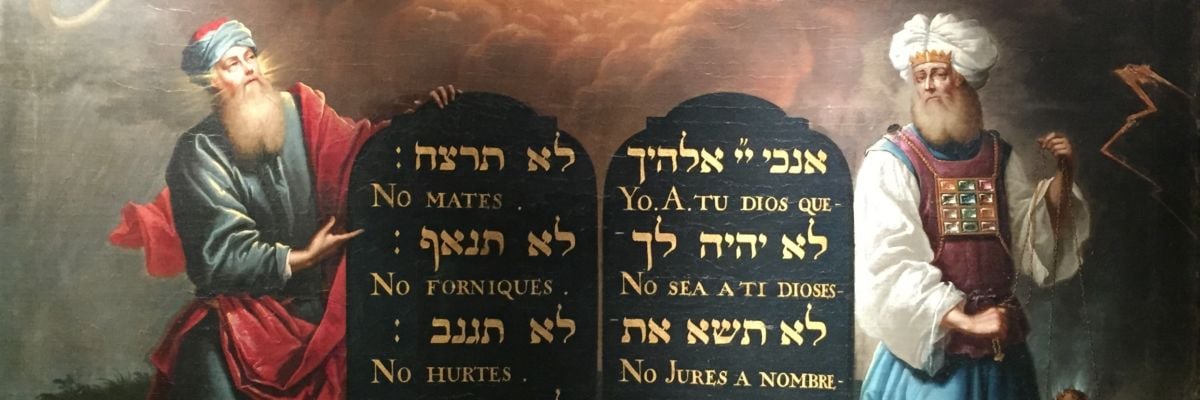

Let’s start with the first reading. I’m not going to read the whole passage since there’s only one line that I want to focus on—namely, God’s instruction that the Israelites not have any “graven images.”

Protestants often appeal to this verse as a challenge to the Catholic practice of putting statues and images in their churches and using them in their private devotions. “How can the Catholic Church approve of religious statues,” so the argument goes, “when the Bible forbids having graven images?”

As I point out in my book Meeting the Protestant Challenge: How to Answer 50 Biblical Objections to Catholic Beliefs, there are two ways we can meet this challenge.

The first way is to prove that God can’t be condemning religious statues and images in an absolute sence, because elsewhere he explicitly commands making them. Consider, for example, the two gold cherubim (cast sculptures of angels) that God commanded to be put on the lid of the Ark of the Covenant (Exod. 25:18-20). God also instructed that cherubim be woven into the curtains of the tabernacle (Exod. 26:1).

When God gave instructions for building the temple during the reign of King Solomon, he commanded that two fifteen-foot tall cherubim statues be placed in the holy of holies (1 Kings 6:23-28) and that “figures of cherubim” be carved into the walls and doors of the temple (1 Kings 6:29). Later, in 1 Kings 9:3, we read that God approved of such things, saying to Solomon, “I have consecrated this house which you have built, and put my name there forever; my eyes and my heart will be there for all time.” God’s blessing on the temple is certain evidence that he doesn’t oppose having statues and sacred images in places of worship.

Another example where God commanded the making of a statue is Numbers 21:6-9. The Israelites were suffering from venomous snakebites; in order to heal them, God instructed Moses to construct a bronze serpent and set it on a pole so that those who were bitten could look upon it and be healed (Num. 21:6-9). God did later command that the bronze serpent be destroyed, but only because the Israelites started worshiping it as a god (2 Kings 18:4).

Now that we know what God is not commanding, the question arises, “What is his commanding?” This leads us to our second response—What God is forbidding here is the making of idols.

The context bears this out. Consider the prohibition that precedes it: “You shall have no other gods before me” (v.3). Then after the passage in question, we read, “You shall not bow down to them or serve them; for I the Lord your God am a jealous God.” Given this contextual prohibition of idolatry, it’s reasonable to conclude that God’s command not to make “graven images” refers to making images to be worshiped as deities, or idols.

Accordingly, we note that every time the Hebrew word for “graven images” (pesel) is used in the Old Testament it’s used in reference to idols or the images of idols. For example, the prophet Isaiah warns in 44:9, “All who make idols [pesel] are nothing, and the things they delight in do not profit; their witnesses neither see nor know, that they may be put to shame.” Other examples include, but are not limited to, Isaiah 40:19; 44:17; 45:20, Jeremiah 10:14; 51:17, and Habakkuk 2:18).

Since making idols is what this commandment forbids, the Catholic custom of using statues and images for religious purposes doesn’t contradict it, because Catholics don’t use statues and sacred images as idols. The whole of paragraph 2132 (referenced above) states the following:

The Christian veneration of images is not contrary to the first commandment which proscribes idols. Indeed, “the honor rendered to an image passes to its prototype,” and “whoever venerates an image venerates the person portrayed in it.” The honor paid to sacred images is a “respectful veneration,” not the adoration due to God alone.

Catholics don’t treat statues, or the people whom the statues represent, as gods. As such, the biblical prohibition of idolatry doesn’t apply.

This challenge from modern Evangelicals shows that there’s nothing new under the sun. The Catholic Church dealt with this sort of objection all the way back in the eighth century when it condemned the heresy of iconoclasm at the Second Council of Nicaea (787). Iconoclasm was the belief that all religious images are superstitious. In response to this heresy, the council declared that religious images were worthy veneration and that any respect shown to a religious image is really respect given to the person it represents.

In having images or statues of Jesus, angels, Mary, and the saints in its places of worship, the Catholic Church is following the Old Testament precedent of incorporating images of heavenly inhabitants that serve as reminders of who is present with us when we approach God in liturgical worship.

The representations of the cherubim in the Old Testament served as reminders that they were heavenly inhabitants present with God. Since humans have been admitted into heaven (Rev. 5:8; Rev. 6:9; 7:14-17), it’s reasonable to employ representations of them, too.

Now we turn to the second reading, which, again, is taken from 1 Corinthians 1:22-25. Here’s what Paul writes,

Jews demand signs and Greeks look for wisdom,

but we proclaim Christ crucified,

a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles,

but to those who are called, Jews and Greeks alike,

Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God.

For the foolishness of God is wiser than human wisdom,

and the weakness of God is stronger than human strength.

The Catholic Church has been a great patroness of philosophical wisdom, with Augustine and Aquinas being perhaps the greatest representatives of this tradition.

But some Christians think this emphasis on philosophy in the Catholic tradition contradicts the bible. And our second reading for this upcoming 3rd Sunday of Lent is a passage that’s often appealed to for support of this claim. “How can the Catholic Church promote philosophy, it’s argued, when Paul clearly says that wisdom is folly? Shouldn’t we stick to the preaching of Christ crucified and leave all that Greek wisdom behind?”

I deal with this objection in my article for Catholic Answers Magazine Online “The Wisdom of God and of the World.” You can access it at catholic.com. Here’s how I respond there.

First, if we take God’s words “I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and the cleverness of the clever” to mean that he disapproves of philosophical reasoning, then he would be acting foolishly, for he would be acting contrary to his nature.

It belongs to our nature as rational animals to have an intellect. And that intellect is naturally directed to contemplating reality. So to engage in philosophy, which is basically the quest to know the ultimate causes of things through natural reason, is a good thing for us as human beings. And whatever knowledge of reality that we can use to direct our lives toward God, which is the virtue of prudence (a sort of cleverness), it’s good that we do so.

Therefore, for God to command us to not engage in philosophical reasoning would be to command us to act contrary to the good of our nature.

Now, for God to command us to act contrary to the good of our nature would be to command us to direct our lives away from him as our ultimate end or goal. In other words, God would be commanding us to not love him.

But God can’t command us to not love him because that would entail a failure for God to love himself, which is impossible given God’s perfect nature. A failure to love himself would involve God falling short of being fully actualized in his loving power. Since that can’t be given that God is pure actuality itself, or pure existence itself, he can’t fail to love himself.

Therefore, it can’t be that God intends to express disapproval of philosophical reasoning when he says, “I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and the cleverness of the clever.” Nor can this be Paul’s intended meaning, for Paul, inspired by the Holy Spirit, would not contradict what we can know by the natural light of human reason.

So what does God, and thus Paul, mean with the words “I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and the cleverness of the clever?”

We can look to St. Thomas Aquinas for some help. In his commentary on 1 Corinthians, he writes,

[God] does not say absolutely, ‘I will destroy the wisdom,’ because ‘all wisdom is from the Lord God’ (Sirach 1:1), but I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, i.e., which the wise of this world have invented for themselves against the true wisdom of God, because as it says in James 3:15: ‘This is not wisdom, descending from above; but earthly, sensual devilish” (Lecture 1-3, 50; emphasis added).

God promises to bring an end by the power of the cross the disordered reason by which human beings strive to live for this world and the goods of this world alone. Again, Aquinas explains,

Similarly, he [God] does not say, “I will reject prudence [cleverness],” for God’s wisdom teaches true prudence, but the prudence of the prudent, i.e., which is regarded as prudent by those who esteem themselves prudent in worldly affairs, so that they cling to the goods of this world, or because “the prudence of the flesh is death” (Rom 8:6).

This tendency to live for worldly affairs alone drives our attempts to explain the world. Just as we tend to live only for the goods of this world, we tend to explain the world only in terms of the things in the world, restricting our explanations to natural causes and not allowing recourse to a transcendent reality or the possible light of divine revelation. This is what Aquinas means when he says in his aforementioned commentary, “[O]n account of the vanity of his heart man wandered from the right path of divine knowledge” (1 Corinthians Lecture 1-3, 55).

According Dominican priest Fr. Thomas Joseph White, in his 2014 Nova Et Vetera article “St. Thomas Aquinas and the Wisdom of the Cross,” it’s this misery of the human condition that the wisdom of God in the crucified Christ heals, “opening [reason] up to an authentic horizon of intellectual universality.” In the words of Aquinas, “God brought believers to a saving knowledge of himself by other things, which are not found in the natures of creatures” (1 Corinthians Lecture 1-3, 55).

A teacher who recognizes his students are missing the poiont, if he wants them to learn, will change track and use another example or explanation to get the point across. Similarly, God recognizing that man has a hard time understanding the meaning of their lives and the world with the language of nature, employs the language of the cross to convey that meaning.

But what’s that meaning? It’s love.

The language of love that Jesus expresses on the cross opens man’s reason up to the reality that we are called to a loving relationship with God the Father, through Jesus Christ, by the Holy Spirit. In the words of Fr. White, the “love of Christ crucified . . . redeems the human mind by introducing it at once to the heights and depths of the mystery of the Trinity.”

And how do we achieve such a loving relationship? By imitating the crucified Christ and offering our lives for others in self-sacrificial love.

So, rather than opposing philosophic wisdom with the wisdom of the cross, Paul, and ultimately God, invite us to allow the wisdom of the cross to redeem human reason and elevate it to the noble place of serving the Faith. The Catholic Church, therefore, can continue being the patroness of philosophical wisdom without fear of contradicting the Bible, ordering philosophical knowledge to its proper end: our union with God.

Okay, let’s now turn to the Gospel reading, which is John 2:13-25, and it’s John’s report of Jesus overturning the moneychangers in the Temple. I’m not going to read the passage because there’s no one detail that I want to focus on. Rather, I want to address a challenge that’s posed by skeptics concerning the placement of this event.

Here’s the objection: John places the cleansing of the temple at the beginning of Jesus’ ministry. But the Matthew (21:12 ff) and Mark (11:15-19) at the end of Jesus’ ministry. How can we trust the Gospels when they don’t even agree on when Jesus did something, like cleanse the temple?

Biblical scholars have offered several ways to reconcile this discrepancy in the Gospels. But there are two that are most prominent.

The first is that John relocated this event for thematic purposes, which is something ancient authors did and were permitted to do. On this view, John put this event at the beginning of Jesus’ ministry as a kind of headline for Jesus’ ministry and a tee up as to what sort of response he would receive throughout that ministry.

The other view is that Jesus did this on two different occasions, at the beginning and the end of his ministry. As many scholars point out, there are enough differences of detail that support a lack of identification.

Furthermore, Jesus would have visited the Temple several times within His public ministry, as John suggests. And given that Jesus isn’t one to remain silent in the face of abuses, and it’s unlikely the abuses in the Temple would have ceased after his first reprimand, it’s not far-fetched to say that Jesus would have done this twice in his ministry.

Since we have plausible explanations of the discrepancy between John and Matthew and Mark, there’s no reason to reject these accounts as historically unreliable.

CONCLUSION

Well, my friends, that does it for this episode of the Sunday Catholic Word. The readings for this upcoming Third Sunday of Lent, Year B provide us with plenty of apologetical material. There’s material that leads to discussions about

- The possession and use of religious statues and images in religious spaces,

- The good of philosophy within the Catholic intellectual tradition, and

- The historical reliability of the Gospels, particularly John’s Gospel.

These are all topics worth reflecting on in preparation for apologetical dialogues.

As always, I want to thank you for subscribing to the podcast. And please be sure to tell your friends about it and invite them to subscribe as well at sundaycatholicword.com. You might also want to check out the other great podcasts in our Catholic Answers podcast network: Cy Kellet’s Catholic Answers Focus, Trent Horn’s The Counsel of Trent, Joe Heschmeyer’s Shameless Popery, and Jimmy Akin’s A Daily Defense, all of which can be found at catholic.com.

One last thing: if you’re interested in getting some cool mugs and stickers with my logo, “Mr. Sunday podcast,” go to shop.catholic.com.

I hope you have a blessed 3rd Sunday of Lent, Year B. Peace!