Audio only:

In this episode Trent rebuts a popular skeptical argument against the Bible that would destroy our modern understanding of history and ancient literature.

No, Christian Apologists Aren’t Proving Spider-Man: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y34Qlg2lXo8

Transcription:

Trent:

Skeptics make lots of arguments against the Bible, but there’s one that stands out as the worst argument because it would destroy our understanding of history if it were taken seriously, and that is the copies of copies argument against the Bible. Skeptics, usually atheists, but sometimes Muslims who are parroting atheist arguments, we’ll say that we can’t know what the Bible originally said because we don’t have the original copies of the biblical texts, and so they could have been radically changed at some point in the copying process. Even critics who should know better pedal this kind of doubt about scripture, like in this interview with New Testament scholar Bart Iman on a pro Islam channel,

CLIP:

We don’t have Matthew’s gospel, we don’t have the original thing he wrote. What we have are copies that were made of that original thing he wrote, and as it turns out, we don’t actually have the first copies and we don’t have copies of the copies and we don’t have copies of the copies of the copy. We have copies that are so the first time we get a complete copy of the gospel of Matthew from beginning to end with a manuscript. The whole thing is 300 years later,

Trent:

Irman is correct that we no longer possess the original manuscripts of the Bible, but here’s why this is a bad argument. We don’t have the original manuscripts of any work that was composed in the ancient world. We don’t have Plato’s original republic. We don’t have the original Jewish histories of Josephus. We don’t have the original Roman histories of Tacitus or the Greek histories of Thucydides. Those books are written on dried leaves or animal skins that were lost, destroyed, or decay over time. But modern scholars can reconstruct the original manuscripts of these works to an extremely high degree of accuracy by comparing all the surviving copies through a process called textual criticism. For example, although we do not have any of Plato’s original writings, we do have about 250 ancient manuscripts that help us reconstruct what Plato originally said. For many other ancient writers, we have only a handful of manuscripts and sometimes only a single copy of the original that itself was written centuries or even millennia later.

But this does not deter scholars for knowing what these ancient texts originally said. So the argument for the Bible’s reliability, at least when it comes to the New Testament, would go something like this one based on manuscript evidence. We are confident that our copies of ancient non-biblical literature accurately reflect what those authors originally wrote. Two, there is greater manuscript evidence for the Bible than for ancient non-biblical literature. Three. Therefore, we should be just as if not more confident that our copies of the Bible accurately reflect what the biblical authors originally wrote. In this episode, I’m going to focus on the manuscripts for the New Testament. If you’d like to see some debate about the textual reliability of the Old Testament, check out Gavin Orland’s recent interaction with cosmic skeptic on the reliability of the book of Isaiah. I find most critics usually agree with premise one until I bring up the when that happens.

Some of them bite the bullet and they say, yeah, you’re right. We have no idea what any of these ancient authors really wrote in the first place, and that’s why I said this is the worst argument. It forces people who want to debunk the Bible to throw out most of history in order to be consistent with their overly skeptical attitudes. It’s why I said in my debate with Matt Dillahunty that his argument about claims not being evidence would destroy most of our knowledge of history. Since nearly all ancient historical evidence are just claims somebody made about what happened in response, some critics say the Bible needs to be held to a different higher standard because what it says about salvation and hell and morality is more important than what Plato or Josephus says about the ancient world. But this argument isn’t convincing. Consider the medicines in your medicine cabinet.

You trust those medicines are what they say they are based on the labels description. So if you have a slight itch, you trust the anti itching cream is really what the label says, it’s, but suppose you’re dying from an allergic reaction and you need one particular kind of medicine to save you. You don’t say, well, this medicine is much more important to my life than anti itching cream. Therefore I need more evidence to know what’s the right medicine than just what the label says. So I’m not going to take it. No, you just take the medicine because it passes the test. All the other medicines pass. You might read the label more than once to make sure you aren’t mistaken, but you don’t need to call the factory for more evidence that it was labeled correctly. Likewise, the potential impact of the Bible on our lives does not justify imposing an arbitrary evidence standard for the Bible that we don’t impose on any other ancient work.

The other objection skeptics make in this context is the Spider-Man argument. They say, well, there are millions of manuscripts about Spider-Man saving people in New York, but that doesn’t mean these events really happened. The Christian Channel testify has a good video debunking the Spider-Man disproves Jesus argument. So I’ll link to it below. My simple response would be that I am not trying to prove the Bible is true via the number of manuscript copies of the Bible. That’s just one part of my whole case. I’m just answering the skeptics claim that our current copies of the Bible do not accurately reflect what the original authors wrote. I’m refuting that claim the truth of what the original authors wrote is a separate issue that I’m happy to address. But before we can do that, we first have to agree on what the original biblical authors wrote, and then we can debate the truthfulness of what they wrote about.

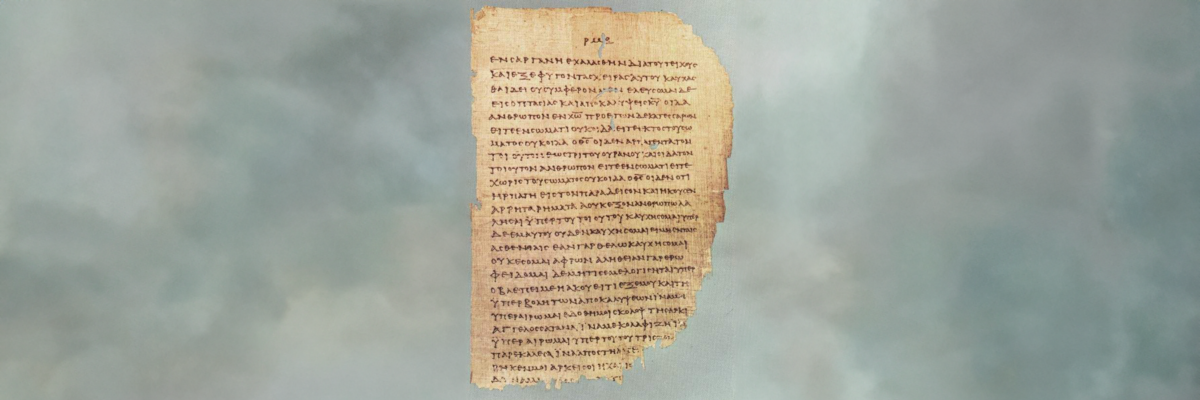

But what makes the New Testament unique different from all their ancient works is both the sheer number of copies we have of it and the reverence people paid to those copies. There currently exist over 5,500 copies of New Testament manuscripts written in Greek as well as 15,000 manuscripts written in other languages like Latin, Coptic and Syriac. 50 of the Greek manuscripts can be dated to within 250 years of the original copies. The first complete copy of the New Testament called Codex Sin Atticus, because it was discovered in a monastery at the foot of Mount Sinai, can be dated to within 300 years of the original documents. Now you might say, wait, how is that impressive? I said, there were 50 New Testament manuscripts in the first two centuries, but that there were 250 manuscripts of Plato’s dialogues. So why is the New Testament more impressive?

Well, that’s true, but when you consider Plato’s dialogues, only two fragments of these 250 manuscripts come from the first 400 years after Plato wrote his dialogue. The oldest complete surviving copy of Plato’s Dialogues comes from 1200 years later, completely different than the 300 years later of the full and complete New Testament that we have or compare this to Homer’s Iliad, which was written in the eighth century before Christ, although a few fragments of the Iliad can be dated within 500 years of Homer, the oldest complete copy of the Iliad, a manuscript scholars referred to as Venus a was written in the 10th century ad 1800 years later, the Biblical scholar ff Bruce put it bluntly, there is no body of ancient literature in the world which enjoys such a wealth of good textual attestation as the New Testament. The reason we have so many copies of the New Testament is that as new church communities sprang up in Europe and Asia, these communities wanted a copy of the scriptures for their public liturgies and for private reading.

During this time, Christianity was illegal within the Roman Empire. So Christians who copy the New Testament scribes endured monotonous hours of writing by hand and risked painful deaths just so others could have a copy of scripture. Although some of these copies have been lost, many others survived do in large parts of the idea that scribe will copying was a way to glorify God. The products of this divine service were then revered and protected for centuries in the sixth century, the monk Casio Doris, who was a contemporary of St. Benedict said the following, what happy application, what praiseworthy industry to preach unto men by means of the hand, to untie the tongue by means of the fingers, to bring quiet salvation to mortals and to fight the devil’s insidious wiles with pen and ink. So much for the anti-Catholic myth that says the church wanted to keep the Bible from people.

Now, these supporters of the Bible were almost as supportive as the subscribers of the Council of Trent who always liked my videos and leave a comment to help the video be better recommended. And the ones who really like our work support us@trenthornpodcast.com where they get access to bonus content and allow our channel to not just exist, but to grow and reach even more people. Another argument that skeptics make is rooted in a claim that comes from Bart Ehrman’s book, misquoting Jesus, where Irman says There are more differences among our manuscripts than there are words. In the New Testament. Scholars believe that there are about 200,000 to 400,000 differences among all the New Testament manuscripts and like snowflakes. No two biblical manuscripts are exactly alike, but this large number of variants should give us hope, not heartache over our ability to reconstruct the original biblical texts.

The reason there are so many variants is because there are so many manuscripts in general. For example, suppose that each of the 20,000 manuscripts in the New Testament we possess has 20 variants in it. This adds up to 400,000 variants. But as you’ll see when this huge number of variances is distributed across a huge number of manuscripts, we are left with individual manuscripts that contain at most only a few dozen variants. In contrast, the New Testament consider the first six books of the Annals of Roman history written by TAUs, one of our primary historical sources about ancient Rome. There exists only one copy of this section of the annals and it was written about a thousand years after the original. It has no variance, but that’s only because there are no other copies for the text to differ with. So this lowers our confidence in the reconstruction of TAUs, even though scholars still do not doubt his text in spite of the paucity of manuscript evidence for it.

A New Testament with many variants distributed across a lot of manuscripts is more reliable than a New Testament with few variants that are distributed across only a few manuscripts, especially since the variance between the manuscripts are almost always trivial and easily fixed. For example, a name or a word might be misspelled but can be corrected by anyone who knows there’s only one N in John. Other times the context makes the correct reading clear as in one Thessalonians two seven where Paul says, but we were gentle Greek ne among you like a nurse taking care of her children. Alternative readings use the similar Greek word epi, but we were little children among you, which doesn’t really change the meaning. However, one manuscript uses the Greek word hip boy, which changes the passage to say, but we were horses among you, which is an outlying scribal error that can be dismissed when compared to all the other manuscripts.

Most of the several hundred variants that remain in the biblical text involve minor issues like these Bible scholar Craig Blumberg puts it this way, only about a 10th of 1% are interesting enough to make their way into footnotes in most English translations. It cannot be emphasized strongly enough that no orthodox doctrine or ethical practice of Christianity depends solely on any disputed wording. There are always undisputed passages one can consult that teach the same truths. Tellingly in the appendix to the paperback edition of Misquoting, Jesus irman himself concedes that essential Christian beliefs are not affected by textual varis in the manuscript tradition of the New Testament. It is too bad that this admission appears in an appendix and comes only after repeated criticism. Now at this point, a critic might object that the vast majority of manuscripts we have come from hundreds or over a thousand years later than the originals, and so they don’t show us what a New Testament looked like during the crucial first centuries of the copying process.

Now, it is important for Christians to not overstate the manuscript evidence for the Bible’s textual preservation. For example, it’s false to say that there are 25,000 or even 5,000 ancient manuscripts from within the first few centuries of church history. The majority of the manuscripts come from the Middle ages. Dozens of manuscripts would be a more accurate term for the ones from the first two centuries of church history. And we should note that many of these are partial manuscripts or fragments, not complete copies. But as I said before, this is far better than other ancient texts that go for centuries without ever having a complete or even a partial manuscript copy being made. Second, we can compare early manuscripts like P 75, which contains large portions of Luke and John’s gospels and has been dated to the late second century to Codex Veta Canus, which has been dated to the early fourth century and contains the entire Bible.

Even though there is a 100 to 150 year difference, both manuscripts have in the words of Greek scholar Daniel Wallace, an incredibly high agreement. This is even more remarkable given that Vaticanus was not copied from P 75. Both manuscripts share an even earlier common ancestor. In fact, new Testament scholar Craig Evans has recently shown that the original text of the New Testament may have survived much longer than we think. He writes the following autographs and first copies may well have remained in circulation until the end of the second century, even the beginning of the third century. The longevity of these manuscripts in effect forms a bridge linking the first century autographs and first copies to the great codices via the early papyrus copies We possess this shows that the first centuries of Christian history were not textual black holes, but that the original documents in the New Testament survived for a long period of time on their own and then survived even longer through multiple independent lines of transmission to the copying process.

And finally, along with the manuscript evidence, we also have the testimony of the church fathers who glorify God by teaching and commenting on the Bible on scripture. Even though the biblical manuscripts they consulted no longer exist, the wording of those manuscripts has survived in the form of quotations in the father’s commentaries on scripture, Bart Ehrman e admitted that this is a resource for textual critics because as he and co-author Bruce Metzker said so extensive are these citations that if all other sources for our knowledge of the text of the New Testament were destroyed, they would be sufficient alone for the reconstruction of practically the entire New Testament. This comes from an academic book that Irman co-authored with conservative scholar Bruce Metzker, and I don’t know if Irman still holds this view. What’s frustrating about Bart Irman is that in his popular level works like misquoting Jesus. He sow seeds of doubt with broad statements that make the Bible seem like it was lost to history. But in his academic works, he presents much more nuanced arguments that aren’t as sensational. William Lane Craig also notes this problem and makes a distinction between good Bart Herman, the scholar, and bad Bart Herman, the popular anti-religious apologist.

CLIP:

Good Bart knows that the text of the New Testament is virtually certain bad. Bart deliberately misrepresents the situation to lay audiences to make them think that the New Testament is incredibly corrupted and uncertain. And it’s very interesting that when the bad Bart is pressed on this issue by someone, he’ll come clean and admit this. For example, I heard Bart Irman interviewed on a radio show sometime ago about misquoting Jesus, and the interviewer was talking to him about how uncertain the text of the New Testament, all the thousands and thousands of variants that there are and how uncertain it is. And finally the interviewer said to him, well, Dr. Erman, what do you think the text of the New Testament originally really said? And Irman replied, I don’t understand what you mean. What are you talking about? And the interviewer said, well, the text of the New Testament, it’s been so corrupted as it’s been copied. What do you think the original text actually said? And Iman said, well, it says pretty much what we have today, what it says now. And the interviewer was utterly confused. He said, well, I thought it was all corrupted. And he says, well, we’ve been able to reestablish the text of the New Testament as textual scholars so he knows and when press admits that the text in the New Testament is 99% established.

Trent:

Also, the fact that we’ve only discovered 50 manuscripts from the first few centuries implies that there were hundreds or even thousands more in circulation at the time that like most manuscripts in the ancient world were later lost. Moreover, we have to remember that these manuscripts also survived in the memories of those who heard them in the liturgy. Thus, these people became living manuscripts. And this also refutes the anti-Catholic idea of the Bible was hidden from the laity. St. Augustine wrote the following to St. Jerome about how the faithful clung to traditional readings of scripture. He writes, A certain bishop, one of our brethren, having introduced in the church over which he presides, the reading of your version, came upon a word in the book of the Prophet Jonah, of which you have given a very different rendering from that which had been of old familiar to the senses and memory of all the worshipers and had been chanted for so many generations in the church.

There upon arose such a tumult in the congregation, especially among the Greeks, correcting what had been read and denouncing the translation as false, that the bishop was compelled to ask testimony of the Jewish residents who was in the town of Oia. Finally, as I noted in my previous episode about the resurrection and Wes Huff on the Joe Rogan show, many of the best resources on defending the textual reliability of the Bible are written by Protestants, several of which I’ve cited in this episode. Wes Huff’s doctoral work is in textual criticism and he does a lot of good Christian apologetics, but there’s also some error in his work, like in his discussion on the elements of the can of scripture and the deutero canonical books of scripture as can be seen in this episode of the Jimmy Aiken podcast. That’s why I would encourage Catholics to learn about defending the historicity and textual reliability of the Bible so they can also confidently defend the sacred scriptures that God has given us. There are some links to books on that subject in the description below. Thank you all so much and I hope you have a very blessed day.