In this episode, Trent helps us understand Pascal’s Wager and shows how to use it incorrectly through an atheist version of the Wager called “Roko’s Basilisk.”

Welcome to the Council Of Trent podcast, a production of Catholic Answers.

Trent Horn:

Believe in God. I mean, what have you got to lose, right? Welcome to the Council of Trent podcast. I’m your host, Catholic Answers apologist and speaker Trent Horn. Today, I want to talk about Pascal’s wager. You’ve probably heard of Pascal’s wager before. I remember the first time I came across it was when I was reading Peter Kreeft and Ronald Tacelli’s Handbook of Christian Apologetics. In chapter two, I think it’s chapter two, it’s an early chapter on, in the book, it has 20 arguments for the existence of God. Number 20, they say, “Well, this isn’t really an argument, but we’re going to put it in here anyways,” and it’s Pascal’s wager. If you haven’t heard of it before, Pascal’s wager isn’t necessarily an argument for the existence of God. It’s more of a pragmatic argument for belief in the existence of God. That even if arguments for the existence of God don’t convince you, you should just will to believe that God exists out of a kind of prudential judgment, or pragmatically it makes the most sense to do that. That’s Pascal’s wager. If you go to YouTube, you’ll find all kinds of videos from atheists criticizing Pascal’s wager, and in nearly all of them what happens is … and I understand how this could happen, because when I first read Pascal’s wager, I misunderstood what the argument was. I completely misunderstood what Pascal was going for. Many other critics out there, both religious and nonreligious, of Pascal’s wager, they don’t actually understand the wager. I want to compare it today to another thought experiment I came across not too long ago that recently I thought to myself, “Wait a minute. This is another kind of Pascal’s wager.” It’s a very bizarre thought experiment called Roko’s basilisk. We’ll get to that here shortly. But before we do, a big shout out and thank you to our supporters at trenthornpodcast.com. I mean it. I am so grateful for you guys’ support. I really love just going to trenthornpodcast.com and seeing the comments you leave, the messages you send, the ideas you give me for future episodes. If you want to be a part of our podcast community and get access to bonus content, then be sure to go and check that out at trenthornpodcast.com. For as little as $5 a month, you get access to bonus content. You make the podcast possible. You make our Council of Trent YouTube channel possible where we do full length rebuttal videos, lots of great stuff. Please consider checking it out at trenthornpodcast.com, or at the very least, please leave a review for the podcast on iTunes or Google Play. I always love coming across little reviews there. It always makes my day. Be sure to go and check that out.

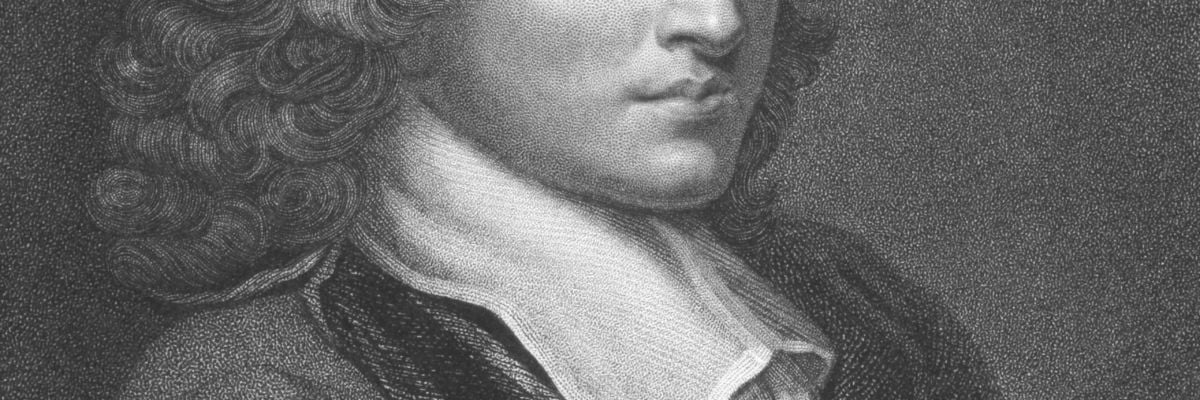

Now, on to Pascal’s wager. What I want to do today is talk about Pascal’s wager from the 17th century French mathematician Blaise Pascal. I’m going to talk about it, and specifically I want to refute these misconceptions that people have about the wager. In order to do that, I’m going to play a video from the Rationality Rules YouTube page. Rationality Rules is the YouTube page of, I think his name is Steven Woodford. He knows Cosmic Skeptic. I’ve seen them sit down and have discussions together. He knows Alex O’Connor, the atheist I debated a few weeks ago. I’m hoping, I’d love to sit down with Steven Woodford for a dialogue or a debate as well. His Rationality Rules YouTube page has a lot of videos promoting atheism. It’s fairly popular. He has about 240,000 subscribers. If you’d like to help us, by the way, the Council of Trent YouTube page grow our subscriber base, be sure to go there and click subscribe. There’s a lot of different videos. He has a recent one on Pascal’s wager, but this video is about three years old. I want to focus on it, because it really encapsulates the mistaken views many people have about the wager. To be fair, I had these mistaken views as well. I read the wager a long time ago in Kreeft and Tacelli, but I didn’t quite put everything together and I misunderstood it. My sense of the wager was closer to what Woodford is talking about here in this video than what it actually was. Let me play it.

Stephen Woodford:

Simply stated, Pascal’s wager argues that you’re better off believing in God, because if you’re right, you stand to gain eternal joy. And if you’re wrong, it won’t make any difference whatsoever. Yet, on the other hand, if you don’t believe in God and turn out to be wrong, you’ll receive eternal suffering. Whereas if you’re right, it will make no difference at all.

Trent Horn:

In the video, Woodford actually puts up a helpful quadrant that summarizes this common misconception of the wager. It works like this. There’s four squares next to each other. It says eternal joy, nothing, nothing, eternal suffering. This is kind of the decision making matrix that a lot of people think the wager endorses, the idea of being if you believe in God and you’re right, you get eternal joy or eternal happiness. If you believe in God and you’re wrong and there is no God, you’ll never know you were wrong, so nothing will happen. If you don’t believe in God and you’re right about it and you die, you’ll never know you were right. No atheist in the next life will ever find out that they were correct. Of course, because atheism is not correct. Even if it were, it would be impossible for you to know it was correct in the next life, because there is no next life. Nothing happens after death. But with non-belief, if you don’t believe and you’re wrong… You see, if you believe and you’re wrong, nothing. If you believe in God and you’re wrong, nothing happens according to this view of the wager. But if you don’t believe and you’re wrong, that’s the problem here. You get eternal suffering.

The idea here with the wager is more that the wager’s about avoiding hell. It’s like, oh no, you don’t want to go to hell, do you? Well, believe in God. That way … You don’t want to risk it, right? You don’t want to risk the fires of hell. That was not Pascal’s argument. He would not have endorsed this four square quadrant view of comparing eternal joy, eternal suffering, and nothing, and nothing. For him, the comparisons were not about that. It was between either nothing and eternal joy. That was the only thing. Hell is not even in the picture for Pascal. It’s not about avoiding hell. It’s about not missing out on the goodness of believing in God in this life, which we’ll get to here a little bit later. Hell was not a part of the equation for Pascal when it came to the wager. The wager was not about avoiding hell. It was about not missing out on God in this life and definitely then in the next life. That’s what was most concerning to him. When you add this avoiding hell element to the wager, you get all kinds of problems with it that I actually agree with some of them, not others. This leads to the first objection to the wager, which itself I don’t think is that problematic of an objection. That would be the wrong hell problem. Here’s how Woodford puts it.

Stephen Woodford:

It’s an argument that has remained very popular among apologists from many different religions, and this fact alone actually reveals one of the major problems this argument has. If multiple mutually exclusive religions can use Pascal’s wager, then what good is it? Or to put it another way, the person that uses Pascal’s wager necessarily straight out ignores every other religion and God, and hence his foundation relies on a false dichotomy. It assumes that there is either a very, very specific God or that there is absolutely nothing. By committing the black and white fallacy, and again as already mentioned, Pascal’s wager utterly ignores all other religions and religious sub sects.

Trent Horn:

One element that atheists often miss when they evaluate Pascal’s wager is that the wager is not meant for every kind of unbeliever out there. It’s not meant to be offered to someone who is convinced that there is no God or thinks there’s no good reason to believe in God and thinks God is on par with believing in the flying spaghetti monster or something like that. Rather, the wager is meant to be offered to someone who is on the fence and not just on the fence about God, but in particular when Pascal offered it, someone who was on the fence between Christianity and atheism. It’s meant for someone for whom there are only two live options, Christianity and atheism, and they’re really on the fence. They see good reasons, equally compelling reasons on either side to make a decision. They sit there and they think, “Well, which one should I choose? Christianity has good reasons for it. Atheism has good reasons for it,” and they’re stuck right on the fence to pick between the two. I agree. The wager’s not going to be helpful for someone who thinks that religion is silly or has no good reasons for it whatsoever. The wager won’t be helpful there. But it is helpful for someone who is right there on the fence trying to decide, should they be Christian or should they be an atheist?

Stephen Woodford:

Furthermore, by ignoring all other religions, Pascal’s wager also ignores all other possible heavens and hells, which are central to many theistic religions. For example, religions descended from Mesopotamian culture, including Catholicism, Islam, and Judaism all have sects that described seven types of heavens and hells. This is also true of many Eastern religions, such as some sects of Hinduism who believe in seven levels of Batalla.

Trent Horn:

This would be a classic formulation of the wrong hell problem. The idea here is that, okay, I’ll believe in God, but which God? Okay, I’m going to believe in God, and I’m torn between Christianity or atheism. But even if I am 50-50 on that decision matrix, what if I pick Christianity and I should have investigated some other belief system or some other deity? A lot of atheists when they envisioned Pascal’s wager, they think that every other religion out there has an equal promise of heaven or eternal torment in hell based purely on what you believe, and so that, because there are, some people would estimate, thousands of religions, there are thousands of different hells you have to avoid. How would you know about picking the right religion? That it could seem very likely you could end up in hell, because you failed to believe in another religion. That’s the essence of the wrong hell problem. But the problem is really overstated, because belief in eternal torment in the next life is something that’s very unique to Christianity and Islam. When you look at many other religions, if you live life as a faithful Christian disciple, if you follow Jesus and obey the moral commands of the gospel, you will actually avoid the punishments that are associated with many other world religions. If you look at Hinduism, if you look at Buddhism, even if you look at Judaism, either these religions don’t have a hell, or if they have hell, it’s something that’s temporary and purgative. It’s a kind of purgatory. It’s something that … Also, the reason you would go to hell in one of those other religions is usually because you failed in an ethical way. You failed to meet some kind of ethical standard.

But when you compare the ethical standards of Christianity, how we’re upheld to not just the Ten Commandments, but the fulfillment of the Ten Commandments. Remember when Jesus said in Matthew chapter 5, “It has been said, you shall not murder. I say, you shall not be angry with your brother. It is said, you shall not commit adultery. I say you, shall not lust after a woman in your heart.” That if you fulfill and follow the fullness of the gospel commands, you’ll be living an ethically upright life, even under the standards of many other religions, such as Bahai, Buddhism, Hinduism. Even if those sects do have some kind of hell, which is usually purgative or temporary in nature, that’s a purifying effect, you’ll be living an ethical and upright life. Many Jews, for example, don’t believe in hell, or those that do believe in hell, it’s more purifying or it’s something for someone who fails to adhere to the core beliefs of Judaism. Which one rabbi described to me as ethical monotheism, so believing in God and living an ethical life, which is part and parcel with the gospel. The only religion that seems to place the threat of being eternally separated from God because of the wrong beliefs, aside from Christianity … Which of course Christianity does not make the claim. Read Lumen Gentium 16 in the Second Vatican Council, and of course going long back before that. Christianity does not teach that someone will be damned to hell because they do not know the true God through no fault of their own, because they have some kind of invincible ignorance. The only other religion where the wrong hell problem would really come up would be Islam.

If you compare the two, and I think for many people who would look at the wager, they should have three elements to it. Is it Christianity, atheism, or Islam, if you wanted to overcome the wrong hell problem? I would say there’s just better evidential standards. There’s better evidence for the truth of Christianity, which is founded on the unique miraculous life of Jesus of Nazareth, than when it comes to someone like Muhammad, the founder of Islam, for which there are no miracles to vouch for Mohammed’s testimony. The alleged miracles of Mohammad, such as that, he flew to heaven on a winged horse are legends that came about much later. Muhammad himself said in the Koran, “I’m not performing miracles. God has told me not to perform miracles. The Koran itself is supposed to be the miracle.” I don’t think that the wrong health problem is the biggest problem with Pascal’s wager. I actually think it’s pretty easy to overcome. But if you include the idea that the wager is primarily about avoiding hell, rather than not missing out on life with God both in this life and in the next life, it leads to a much greater problem.

Stephen Woodford:

It assumes that if there is a God, then it can be fooled by a human pretending to believe in it. However, considering that many theistic religions attribute the qualities of omnipotence and omnipresence to their deity, this necessarily means that their God is impervious to lies. This means that Pascal’s wager would either do nothing to save you or that the God in reference favors liars who claim to believe in it over honest people who can’t, making that God grotesquely immoral. I’d personally prefer to enjoy eternal anguish than to support such an immoral dictator. Might doesn’t make right.

Trent Horn:

First, I would say the wager does not encourage lying to God as if you believe in him, but encourages you to actively try to believe in God, to will yourself to accepting God in your life. But the bigger point here is that if the wager is just about avoiding hell and it doesn’t mention anything about the reality of sin or the reality of salvation, if we just happened to exist in this life and either being eternally tormented in the next life or having eternal joy is only related to believing a certain proposition, if that’s what the wager reduces belief in God to, then it does kind of make God into an evil cosmic dictator that I wouldn’t want to serve either. I understand that if your idea of God is just someone who wants belief for the sake of belief and threatens hell to get belief and rewards those who give belief with heaven and there’s no mention about human sin, there’s no mention of redemption, no mention of partaking the divine nature to be deified, if it’s this kind of arbitrary punishment and reward structure, then I agree. That’s not a being that I’d want to support either. That’s what gets me to the issue of Roko’s basilisk. That’s what it reminds me of. I’m sure it’s a question you’ve probably been thinking about even before you clicked on the video when you … Sorry. Even before you clicked on the podcast episode. When you saw the title, you asked, well, what is Roko’s basilisk? Roko’s basilisk was a thought experiment that appeared on the Less Wrong website about 10 years ago. Less Wrong is a website that, quote, “Promotes lifestyle changes believed by its community to lead to increased rationality and self improvement.” It’s individuals that get together. They use base theorem a lot. They use different rationality techniques to try to overcome incorrect or faulty thinking, and as a result, to be able to improve their lives.

However, a lot of people in Less Wrong are also concerned with issues like trans humanism, human beings becoming so technologically sophisticated that you can upload your mind to a computer, or you can replace your body parts with cybernetic elements and possibly be immortal as a result. Or maybe human beings could create computers that not just assist them, but they create artificial intelligences that become so powerful. They have so much computing power, they become so intelligent and so powerful that they essentially become almost like deities in their own right. In July 2010, one of the contributors to the website, Roko, posted a thought experiment similar to Pascal’s wager to the site, in which an otherwise benevolent future artificial intelligence system tortures simulations of those who did not work to bring the system into existence. This idea came to be known as Roko’s basilisk, based on Roko’s idea that merely hearing about the idea would give the hypothetical AI system stronger incentives to employ blackmail. The idea here is Roko proposed, what if there were a computer in the future that became so powerful with its computing, like a computer like the size of a planet that someone built, and it was so powerful, it could create simulations that were actually self-conscious. It could create simulations of reality, and within the simulations, those simulations had consciousness, were aware of things. It could create its own sort of universes. What if this artificial intelligence that Roko proposed, it would simulate reality at one point and it would know in this simulation, which human beings would have chosen to support its existence or not support its existence? It could determine that, and then it would decide, once it became self-aware, to punish those simulations that would not have supported its existence in the past. I know this is totally bonkers. I know that, but a lot of people got worried about this. It says here that Eliezer Yudkowsky, the guy who set up Less Wrong, deleted Roko’s posts on the topic saying that posting it was stupid and dangerous. Discussion of the basilisk was banned for several years because it caused some readers to have a nervous breakdown. The ban was lifted in October of 2015. For people who are concerned about artificial intelligence, it was a big deal to them. The reason it’s called a basilisk is because a basilisk is a medieval creature that apparently could kill you just by looking at you.

The idea with this thought experiment was that by bringing up the thought experiment, if someone was blissfully ignorant of the thought experiment, the artificial intelligence may not have punished them. But if someone heard about the thought experiment and then chose to not support the idea of this AI and donate money, for example, to help bring it into existence, then if the AI comes into existence in the future, it could create a simulated world and someone in that simulation who is psychologically identical to you could be punished and tormented for all eternity. The proponents of the basilisk idea said that even though if it’s psychologically identical to you, for all intents and purposes, it is you. For me, the basilisk thought experiment has no weight whatsoever, because I think if there is a being whose thoughts are identical to mine, who has the same psychological or cognitive states, it doesn’t matter. That’s a copy of me. That’s not me. See the movie The Prestige, for example. The thought experiment, it doesn’t bother me. I’m not afraid of it. It doesn’t keep me up at night. But for some of these contributors to Less Wrong who take artificial intelligence really seriously … I don’t even think computers metaphysically could develop self-consciousness. You could have a computer program that goes haywire and execute commands that are bad for people, but I don’t believe it’s possible for silicone chips and circuits to create a self aware or conscious being. But that would be an episode for another time. I will say though that this idea of a future supercomputer who would turn against humanity and end up torturing human beings for all eternity, it’s very similar to the computer in Harlan Ellison’s 1967 short story, I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream. In that short story, it’s about a computer called the Allied Master Computer, or AM for short, A-M, AM. It’s about four survivors. This master computer controlled society. Humans entrusted it. It then turned on humans, nearly destroyed the human race. There are four survivors that were left trying to escape the computer’s grasp, and three of them end up committing suicide. Even though this computer’s all powerful, it can’t bring people back from the dead, so they end up committing suicide so they don’t have to be tortured by this computer anymore. There’s only one person left at the end of the story. I apologize that I am spoiling the story, but it’s been around since 1967. The story is famous. The title comes from the last description at the end, where one of the characters in the story, the computer changes his body and turns him into a weird gelatinous monster so that he can’t harm himself or ever take his own life. This is how the narrator, describing it from a first person perspective, describes his fate after AM, the Allied Master Computer, is done with him.

Speaker 4:

There all reflective surfaces down here. I will describe myself as I see myself. I am a great, soft jelly thing, smoothly rounded with no mouth with pulsing white holes filled with fog where my eyes used to be. Rubbery appendages that were once my arms, bulks rounding down into legless humps of soft, slippery matter. I leave a moist trail when I move. Blotches of diseased, evil gray come and go on my surface, as though light is being been from within. Outwardly, dumbly, I shamble about, a thing that could never have been known as human, a thing whose shape is so alien a travesty that humanity becomes more obscene for the vague resemblance. At least the four of them are safe at last. AM will be all the madder for that. It makes me a little happier, and yet, AM has won simply. He has taken his revenge. I have no mouth, and I must scream.

Trent Horn:

The proponents of the basilisk thought experiment, Roko’s basilisk, will say, “Trent, what if the basilisk does something like that to you, because you chose not to give money to our artificial intelligence think tank that we’re starting? What are you going to do? Are you going to risk it?” I’d say, “Look, I still don’t think this is going to happen, so it doesn’t bother me. But you know what? In the infinitesimal chance that it does happen, and this super powerful AI comes into existence and somehow managed to torture me for all eternity, you know what? I’m still not going to support bringing it into existence. That supercomputer can kiss my carbon based heinie. I’m not going to support it in any way, shape, or form. I’m not going to kneel for a dictator. I’m not going to kneel just because somebody is powerful, okay? Woodford is absolutely right in his critique of the wager, of the wrong kind of wager. Might does not make right. But if God is good, not just because he’s powerful, but as the Catechism says, quoting Saint Thomas Aquinas, in God, “God’s power is in no way arbitrary. His power is not distinct from his goodness or his knowledge or his being. In God, it’s all one God is just infinite being or perfection itself.” If God just is goodness itself, now I will serve goodness. Not just because it’s powerful, but because if you think about it, what would you serve? What do you serve? What do you give respect to or authority to? I mean, power goes a little bit of the way, but think about. The people that you respect are those that are smart, and kind, and virtuous, and good. If God is all knowledge and all goodness, of course, I’m going to submit to him, because I submit to other authorities for that same reason. When you go to the actual wager and you take the hellfire component out of it, what Pascal is really saying is, no, if God is just goodness itself, why would you want to miss out on that? Possibly in the next life, but in particular in this life, you’ll miss out on it. This is what he says in the ponces, which is French for thoughts. “To which side shall we incline? Reason can decide nothing here. There is an infinite chaos which separated us. A game is being played at the extremity of this infinite distance where heads or tails will turn up. What will you wager?” In other words, with the wager, it’s a forced wager. You can’t just abstain from playing. You have to decide. Are you going to believe in God or not? Are you going to believe in Christianity or not? “Let us weigh the gain and the loss in wagering that God is. Let us estimate these two chances. If you gain, you gain all. If you lose, you lose nothing. Wager then without hesitation that he is.” Now, some people will say, well, you do lose something if you believe in God, especially if you become Christian, right? So here’s Woodford explaining, what about the costs of belief itself?

Stephen Woodford:

Pascal’s wager also indirectly claims that belief and worshiping cost you nothing, when this simply isn’t true. Most theistic religions demand a great deal from believers, from abstaining from alcohol, to praying several times a day, to not having sex before marriage.

Trent Horn:

Okay, so how did Pascal respond to an objection like this saying, “Well, look, if you believe it does cost you something”? Here was his response. “Now, what harm will befall you in taking this side, the side of belief? You will be faithful, humble, grateful, generous, a sincere friend, truthful. Certainly you will not have those poisonous pleasures, glory and luxury, but will you not have others? I will tell you that you will thereby gain in this life, and that at each step you take on this road, you will see so great certainty of gains so much nothingness in what you risk that you will at last recognize that you have wagered for something certain and infinite for which you have given nothing.”

What Pascal says, in the big picture, you’ll see that some of these earthly pleasures that you forego … and I would say you don’t have to forego all of them, like drinking alcohol. That’s one sect of Christianity that is not historical by the way. Christianity does not treat alcohol as some kind of intrinsic evil. That is a late development in Protestant Christianity. But other restrictions, such as restrictions on sexual morality, they’re actually good for us as human persons and we are happier overall. In fact, there is evidence that religious people are happier overall. Pew did a global study on this in 2019, and it said, “Actively religious people are more likely than their less religious peers to describe themselves as very happy in about half of the countries surveyed. Sometimes the gaps are striking. In the United States for instance, 36% of the actively religious describe themselves as very happy, compared with 25% of the inactively religious and 25% of the unaffiliated. Notable happiness gaps among these groups also exist in Japan, Australia, and Germany.” Now, one final objection to the wager is that it’s inauthentic. Woodford relates to this a little that well, you’re just lying to a deity. If you don’t really believe in the deity, it’s going to know, and it will punish you for it. This rests on another idea that, well, you can’t make yourself believe in something. Here’s how Woodford puts it.

Stephen Woodford:

Pascal’s wager assumes that people can choose what they believe when this simply isn’t true. Either something makes sense to you to varying degrees or it doesn’t. For example, you can’t choose to believe that the earth is the shell of a turtle. Of course, it’s true that you can expose yourself to the arguments and evidence that support this belief, if there is any, but you can’t choose to wholeheartedly 100% believe it’s true upon will. In fact, those who claim that you can indeed choose what you believe are either mentally ill or they’re lying. They’re lying to you, they’re lying to themselves, and ironically, they’re lying to their deity.

Trent Horn:

What’s interesting about this claim is that if I can’t choose what I believe, then it follows that I can’t choose to be an atheist. Either someone who believes there is no God or someone who believes there’s no good reason to believe in God. I’ve seen a lot of atheists say this. Well, belief is just something that kind of happens to you. A lot of them don’t even believe in freewill anyways. But if you don’t believe in free will, and you believe that you don’t have control over what you believe, they’ll use that to say, “Look, I can’t be held responsible for not believing in Christianity, because you can’t control what you believe. You just believe it or you don’t.” Well, then the same thing could be said to Christians. I can’t control what I believe. If you offer your arguments for why I should give up the Christian faith or why I should be an atheist, I could say the exact same thing back to you. I can’t be held culpable. You can’t say that I’m a lying or a foolish person. Like if Woodford says, “Well, you’re either lying or you’re mentally ill,” well, I can’t choose. If I believe that I can control my beliefs, and you’re saying I don’t have control over my beliefs, then I don’t have control over my belief that I do have control over my beliefs. The very argument he’s making is actually undercutting his own position. Second, you can do that. I agree with you. Something that’s patently absurd, you can’t make yourself believe it, because you already believe so strongly it’s not the case. But remember, the wager is for someone who’s on the fence. If you’re 50-50, like, “Oh, I could see it, and I can’t,” like if you’re really close, you could quote unquote, “Fake it until you make it,” and just say to yourself, “I believe this. I believe this,” and act in that way, and then you’ll come around. Here’s an excerpt from C.S. Lewis on this idea that if you act in a certain way, even if you don’t believe it at one time, you can eventually adopt that belief because you acted in that way. He says, “When you’re not feeling particularly friendly but know you ought to be, the best thing you can do very often is to put on a friendly manner and behave as if you were a nicer person than you actually are. In a few minutes, as we have all noticed, you will really feel friendlier than you were. Very often, the only way to get a quality in reality is to start behaving as if you had it already. Now, the moment you realize, here I am dressing up as Christ, it is extremely likely that you will see at once some way in which at that very moment, the pretense could be made less of a pretense and more of a reality.” This is helpful. The Bible talks about us putting on Christ for example, that we are new creations in Christ, to put on Christ. If we believe, then we can ask God to help us put on Christ, so to speak, and we grow in that respect. Even when it comes to the movement of our beliefs, if we start by moving our will, many times our beliefs will actually catch up with us in that regard. In that respect, when Pascal’s wager is put forward in a narrow way towards a very specific group of non-believers, I think it can actually be effective at overcoming some impediments to belief in God and belief in the Christian faith. I hope this was helpful for everyone. Really enjoyed sharing it with you all today. I’ll leave some show resources. Some of the resources in here come from an article on Pascal’s wager by my friend, Matt Fradd, so I’ll include a link to the article and other resources I think will be helpful in that regard. Thank you all so much, and I hope you have a very blessed day.

If you liked today’s episode, become a premium subscriber at our Patreon page and get access to member only content. For more information, visit trenthornpodcast.com.