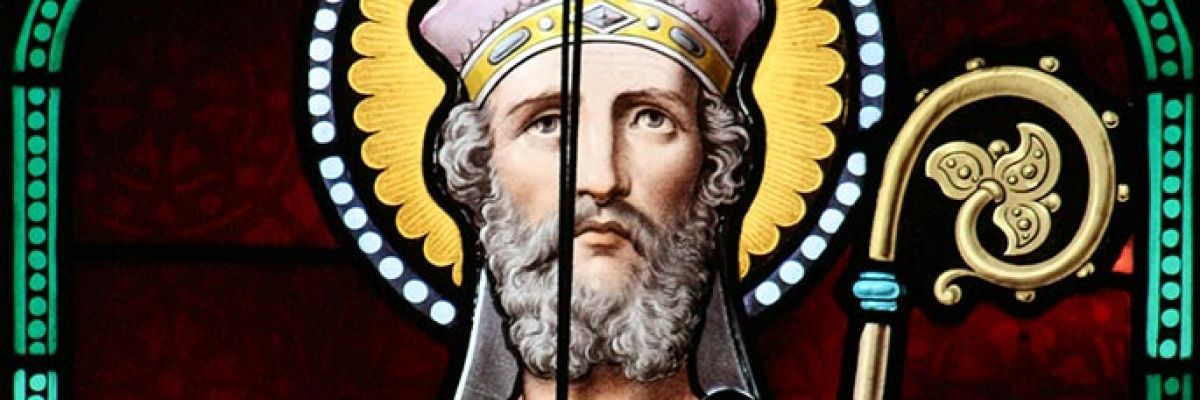

In honor of St. Anselm’s feast day Trent takes a look at the ontological argument: one of the most interesting arguments for the existence of God first developed by St. Anselm of Canterbury in the 11th century.

Welcome to the Council of Trent podcast, a production of Catholic Answers.

Trent Horn:

What if you could prove the existence of God from the dictionary alone? Welcome to The Council of Trent podcast. I’m your host, Catholic Answers apologist and speaker, Trent Horn. And before we get started, I want to give a big thanks and shout out to our supporters of Trenthornpodcast.com. You guys have been awesome, especially during this really difficult time in our country’s history. I’m so grateful for your support. And if you’d like to support our podcast, consider going to Trenthornpodcast.com, where for as little as $5 a month, you get access to bonus content, the exclusive ability to comment on episodes, to message me, to be able to submit questions for our open mailbag episodes, all that and more at Trenthornpodcast.com. Or consider leaving a review at iTunes or Google Play. That’s always a big help as well. Now onto the topic of today’s episode.

Today we’re going to talk about the ontological argument for the existence of God. Why are we doing that? Because today is the Feast Day of the argument’s inventors, Saint Anselm of Canterbury. So Saint Anselm was a Benedictan monk and Abbott philosopher and theologian, who was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1093 to 1109, so during the 11th and beginning of the 12th centuries. For his resistance to the English Kings William II and Henry I, he was exiled twice from 1097 to 1100 and once again from 1105 to 1107. So he writes a lot on philosophy and theology. Anselm is also saint known for putting forward the satisfaction theory of the atonement, the idea that Christ’s death on the cross essentially satisfied the debt that we owe God from our sins. I think I’ve gotten into that before in a previous podcast on the atonement, and I’m sure I’ll return to it if I do a future podcast just on the nature of the atonement and looking at a common Protestant view of it called penal substitution, because I think that the satisfaction view Anselm puts forward is far superior of a model.

But that’s not we’re talking about today. Today, we’re talking about what Anselm is most famous for worldwide in the history of philosophy, and that is his ontological argument for the existence of God. Now there’s lots of arguments for the existence of God. There’s 20 of them in Peter Kreeft and Ronald K. Tacelli’s book, A Handbook of Christian Apologetics. So there’s a whole bunch of different ones you can pick in there. One of my favorites in there, I think it’s argument 18 probably, it goes like this. There is the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. Therefore there is a God. You either see this one or you don’t. I love how Peter Kreeft puts things. And so a lot of the arguments in there, you’ve got your classic arguments, like the cosmological argument, the teleological or design argument, the moral argument. And there are tried and true good arguments.

But there’s some arguments to the existence of God that are delightfully quirky. This one, the ontological argument, I would say it’s got a lot of chutzpah. Chutzpah is a Yiddish word that means a kind of impressive audacity or a reckless self confidence that other people begrudgingly respect. So chutzpah is like, “Wow, you are totally crazy to do that, but I kind of respect you a little bit for doing that, even though you’re totally out of your mind.” That would be chutzpah, and I really believe the ontological argument has a lot of chutzpah, because it tries to show that God, by definition, must exist.

So most arguments to the existence of God, they’ll start with you look around at the world and say, okay, we’ve got this feature of design, these moral values, or even the universe itself cries out for an explanation for God. Psalm 19:1 says, “The heavens are the handiwork of God. The sky proclaims the builder’s craft.” Romans 1:20, St. Paul says that ever since the beginning of creation, his eternal attributes, his invisible attributes of power and divinity have been made known in that which he has created. So most people come to a knowledge of God by saying, “Hey, look at this world around us. It logically goes back to some kind of transcendent creator or cause.”

But Saint Anselm had a different idea. He said if you thought about what God was, the definition of God itself, it implies that God must exist. So here is his original text in his work [inaudible 00:04:18], and this is kind of the basis for ontological arguments. And as we’ll see, there’s more than one kind of argument. Just as there’s a family of cosmological arguments, or arguments that try to prove God exists from the existence of the universe, ontological, so ontology means being or existence, so ontology deals with being, what exists, what doesn’t exist, so there’s really a family of ontological arguments that try to show God must exist by definition, and we can know that from reason.

So if there’s a family of ontological arguments, the one that I’m going to share with you right now, this is the great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great-grandfather, the progenitor of all of them. And this is how Anselm puts it, “Even a fool, when he hears of a being than which nothing greater can be conceived, understands what he hears. And what he understands is in his understanding. And assuredly that, then which nothing greater can be conceived.” That’s what he means by God, by the way, God is that which nothing greater can be conceived. So keep following. “Assuredly that, that then which nothing greater can be conceived, cannot exist in the understanding alone.” So Anselm says even an idiot knows what God is and has an idea of God and his mind, but that idea of God can’t be in his mind alone.

He goes on, “For suppose it exists in the understanding alone. Then it can be conceived to exist in reality, which is greater. Therefore, if that then which nothing greater can be conceived exists in the understanding alone, the very being than which nothing greater can be conceived is one than which a greater can be conceived.” So what he means is, okay, so I can think of God, that which nothing greater can be conceived. I can’t think of anything bigger than God. I can think of that in my mind. But wait a minute, I can think of something even greater than that. He goes on to say, “But obviously this is impossible, that I can think of something as great as can be conceived in my mind, yet it could be greater if it exists in a reality.”

So he goes on to say, “There is no doubt that there exists a being than which nothing greater can be conceived, and it exists both in the understanding and in reality.” So Anselm’s argument is basically this, God is the biggest thing you can think of, not biggest and size with biggest and greatness. You can’t think of anything greater than God in power, knowledge, goodness, existence. So when I mean biggest, I mean greater. God is the biggest thing you can think of, right? Okay. So are you thinking of God in your mind? Sure. Biggest thing I can think of is God in my mind. But you could think of one thing greater than that. So that thing you’re thinking of can’t be God. Because what’s bigger than God in my mind? God in reality, of course. So there’s nothing greater than a God who actually exists. Therefore, God exists. And that’s the argument.

Most people recognize that’s chutzpah. That’s got a lot of chutzpah there. You’re going straight from the definition of God to the idea that God must exist. Even people who are religious, even Christians have problems with this. I have problems with this argument, at least this version of the argument. They say, “Wait a minute, something isn’t quite right here.” And that goes all the way back to when the argument was first formulated. So, a monk at the time of Anselm, named [inaudible 00:07:37], what he said was, “Hold on, a minute, Anselm. You’re saying I define God as the greatest possible being, that I can’t think of anything greater than God, therefore God must exist.” He says, “But you could use this same kind of thinking to prove anything exist. And if you could use this thinking to prove anything exists, then it proves nothing exists. It doesn’t prove anything then. If it can prove anything, it proves nothing.”

This was [inaudible 00:08:02] objection. Here’s how he goes, “Now if someone should tell me that there is an island than which none greater can be conceived, I should easily understand his words in which there is no difficulty. But suppose that he went on to say as if by logical inference, you can no longer doubt that this island, which is more excellent than all lands exists somewhere since you have no doubt that it is in your understanding. And since it is more excellent not to be in the understanding alone but to exist both in the understanding and in reality, for this reason it must exist.” And so [inaudible 00:08:37] is basically saying, “So if you’re saying that this proves that God exists because God is that which no greater can be conceived, doesn’t this kind of argument also prove that an island than which no greater can be conceived also exists?”

And [inaudible 00:08:52] objection is one that atheists have run with for a very long time. When you hear atheist object to the ontological argument today, the first objection they make is usually [inaudible 00:09:01] objection, which is actually one of the weakest objections to the argument. Because there’s a difference between the most perfect island, or people will also say, “How about a lion than which no greater can be conceived? Or a basketball player than which no greater can be conceived?” Or the late atheist Victor Stenger, in a debate with William Lane Craig, this was one where Craig used the ontological argument, even though he rarely does, Stenger said, “Okay, if that ontological argument proves God exists, then maybe a maximally great pizza, a pizza no greater than can be conceived, the greatest pizza you can imagine, must exist by definition.” And so Stenger tried to show that that’s silly. But Craig points out that things like a most perfect island, or in this case a pizza than which no greater can be thought, or a maximally great pizza, is not the same kind of thing as God. And I’ll explain why here in a moment. But it’s not the same kind of thing. It lends itself to contradiction, so it couldn’t possibly exist either in the understanding or in reality. Here is how Craig puts it.

William Lane Craig:

This was the first time I’ve ever put forward the ontological argument in a debate situation. And he, as a non-philosopher, was rather flummoxed by the whole thing. He really didn’t know what to respond. And so all he said was that if the ontological argument were sound, then you could argue that there must be a maximally great pizza. And that because a pizza that is maximally great would have to exist, therefore, if a maximally great pizza’s possible, therefore there is a maximally great pizza. And as I pointed out, that’s really not a very good parody of the argument.

Speaker 4:

The pizza I had last night was not maximally great, by the way.

William Lane Craig:

Well, I don’t think there is such a thing as a maximally great pizza. It’s not even a coherent idea. Think about it, Kevin, a pizza is something that can be eaten and digested, and therefore it cannot be metaphysically necessary. The idea of a metaphysically necessary pizza is just a logically incoherent idea.

Trent Horn:

So the point here is that [inaudible 00:11:10] objections don’t work because a maximally great island or pizza or an island than which no greater can be thought or a pizza that which no greater can be thought or a basketball player than which no greater can be thought, those things don’t actually exist. They’re logically incoherent. They don’t have what’s called an intrinsic maximum. So for example, what would make an island so great you couldn’t think of a greater island? Well, there’s no such thing because you could always add one more coconut tree, one more beautiful inlet cove, a one more luau. You could always keep adding things to this island to make it greater, and you would never reach any kind intrinsic maximum. Or for a basketball player than which no greater can be thought, he could always be taller, he could always shoot more baskets. He could always run faster. There’s not really intrinsic maximums. Or if there were, they would start to contradict one another so that he couldn’t even be made of matter anymore to be able to do things faster than the speed of light. But then if he’s not made of matter, he’s not a basketball player.

Or with the pizza, a pizza than which no greater can be conceived, you could always add one more topping to make it greater. So there is no pizza than which no greater pizza can be conceived and so it must exist. Or if it’s a pizza that is maximally great that has to exist in every possible world, and we’ll get to possible worlds here in a moment, a pizza by definition, you have to be able to eat it, as Craig points out. And so if you ate the pizza, it couldn’t be that which no greater can be conceived because it could be eaten, it would not exist anymore.

So when people try to parody the argument to say that it could prove anything, that doesn’t work because God has attributes that have intrinsic maximums, like omnipotence, doing all logically possible things; omniscience, knowing all things that can be known; necessary existence, existing in all times and spaces or never failing to exist. So we could imagine that kind of being and think of it in our minds. But then we have to wonder, well, the fact that I can imagine it, does that show that it has to exist? And now from there though most philosophers throughout history have said, “No, it doesn’t follow.” Just a few centuries later, St. Thomas Aquinas, he doesn’t mention Anselm, but he seems to kind of throw shade at him, if you will, to borrow a 21st century lingo, Thomas says in the Summa Theologiae, “No one can mentally admit the opposite of what is self evident, as Aristotle states concerning the first principles of demonstration, but the opposite of the proposition, God is, can be mentally admitted. The fool set in his heart there is no God, therefore that God exists is not self evident.”

Edward Feser, who is a prominent [inaudible 00:13:58] philosopher, this is how he phrases Aquinas’s objection to Anselm’s argument, “The lesson is not that Anselm’s argument is unsound so much is that it presupposes knowledge of God’s essence, or what he’s like, that we cannot have. Moreover, the idea that reason points us to the existence of that than which there can be nothing greater, is something Aquinas himself endorses, as long as it’s developed in an [inaudible 00:14:26] fashion, as in the fourth way.” So what that means is Aquinas would agree with Anselm’s definition of God, God is that which nothing greater can be conceived. But we only know that that is the definition of God according to Aquinas’s metaphysics, because we arrive there by looking at the world around us and finding its ultimate source.

So Aquinas, his fourth way, his fourth proof for the existence of God, one that Dawkins totally bites the dust and misunderstands, the fourth way is kind of similar to the ontological argument because Aquinas says, “What we see in the world exists in various grades of being or perfection. And if we follow these grades of perfection, there must be a most perfect being. And therefore God exists.” And so Dawkins in the God Delusion, he says, “Well, if that’s the case, then there must be a fart, a farter, a smelly farter who is smellier than that which can possibly be conceived because there are farts that are so smelly, there must be a farter of maximum smelliness.” So he once again tries to parody it. But Aquinas would jump back and say, no smelliness or farting or not great-making properties. In fact, putrid smell is a deficiency. It’s a kind of physical evil. So physical evils aren’t greater and greater things. They don’t have real being, they’re privations of goodness, they’re the absence of being.

So basically though that Aquinas, and then later, if you go to Emmanuel Kant in the modern age, Kant said that look, existence is not a predicate. This is the modern objection to Anselm. Kant said this, “If I take the subject God with all its predicates, what we say about it, omnipotence being one, and say God is or there is a God, I add no new predicate to the conception of God.” So he goes on to say, “I merely posit or affirm the existence of the subject with all its predicates.” So Kant’s objection, which is one that most philosophers today will hold to, not to [inaudible 00:16:14], they’ll still talk about [inaudible 00:16:16], the most perfect island, but they’ll say that Kant made the point that you can’t just predicate existence to something. It has to exist in order for you to say certain things about it.

You can’t say all Anselm’s argument would prove to modern critics is that if God existed, then he would be that which no greater can be thought. But it doesn’t follow that just because he is that by definition that he exists in reality. They would say that it’s not really… They would disagree with Anselm and say Anselm is wrong when he says it is greater for something to exist in reality than in the mind. They would say that that kind of existence is not a predicate you add to something. It is just something a thing would already have in virtue of being an existing subject or not.

So that’s Anselm’s arguments, the great grandfather to the ontological argument, as I said. But they’ve developed since then, especially in the 20th century. We’ve seen people like Malcolm Hawthorne, and then of course Alvin Plantinga is very famous. And Ben Arbor actually sat down, I think this is a few years ago, with the Capturing Christianity Channel with Cameron Bertuzzi, great guy, he was just interviewed by Matt Fradd on Pints with Aquinas. I definitely recommend you go and check that out. Cameron’s a good guy. He does a lot of good work promoting the defense of Mere Christianity. He’s Protestant, but he’s focusing mostly on defending the existence of God, the resurrection of Christ. Good channel, Capturing Christianity. And he had an interview with Dr. Ben Arbor about the ontological argument. And this is what Arbor says, talks about how the argument progressed since the time of Saint Anselm in the 11th century to today.

Dr. Ben Arbor:

And I have concerns about his formulation of the argument as to whether or not it’s successful. But fast forward 900 years and here we are in the 21st century. And in the late ’70s, Alvin Plantinga developed an argument that’s now called the modal ontological argument. And it doesn’t trade on the conceivability premise that Anselm’s argument did. He said, not that God is the greatest conceivable being, but that God is the greatest possible being. Whether you and I can think about it or not, that’s an ancillary question to the idea that something that’s out there, of all the extant stuff, something is the greatest. Think of it as like a food chain, right? Something’s at the top of the food chain or something’s at the top of the totem pole. And he thinks God is that. But not just that there’s something out there that’s at the top of the food chain, but that whatever actually is at the top of the food chain, it’s not possible that there be anything greater than that. And that whole idea is baked into the definition of who God is.

Trent Horn:

So that’s how the ontological argument has progressed. It moved beyond Anselm’s epistemic view, where it starts with God being something I conceive in my mind, and uses a modern development in logic called modal logic. So modal logic deals with possibility and necessity. And it can get very complicated very quickly. So I’m not going to go to the ins and outs of modal logic. Because if you read articles on the ontological argument and modal logic, you quickly deal with things like the S5 axiom in modal logic and possible necessity and necessarily possible. And it’s a lot I don’t want to weigh down on you all here.

But what I want to do though is get you into the modern version of this argument. This is Alvin Plantiga’s version. Plantinga is one of the most famous 20th century philosophers of religion in the world. He taught at University of Notre Dame. I think he’s still affiliated with Notre Dame. And back in the 1950s and ’60s, his claim to fame was publishing a book called God and Evil, where he showed that the problem of evil was the logical problem of evil was not a decisive refutation to theism, to the belief in God. And he refuted J.L. Mackie at the time. And so Plantinga showed that no, the logical argument from evil does not disprove the existence of God. Actually, he ended up showing the logical argument from evil basically doesn’t work. There’s still atheistic philosophers today who tried to resurrect the argument, but Plantinga dealt it a pretty swift blow that even agnostic and atheistic philosophers, people like Paul Draper, say that theists don’t really face a serious problem from the logical problem of evil, saying that God and evil are logically contradictory. Most atheists today will just say that the amount of evil in the world makes God’s existence unlikely, not impossible.

And the reason they make that shift is because of the work of Alvin Plantinga. And Plantinga has done other arguments. He’s defended rational belief in God, why we’re warranted to believe in God, even if you don’t follow a bunch of fancy arguments. And then he puts forward this ontological argument. This is how William Lane Craig summarized the argument. Well actually, I’ll tell you what, before I get to that, before I get to how Plantinga puts for that argument, I told you just how amazing illuminary this guy is. One of my favorite videos online, I’ll have to put this in the link for the show description, is… So he lives near Notre Dame, where is that? Indiana, I think. Sorry. I’ve been up late last night, I can’t remember. And so Plantinga was in a news segment about how where he lived there was a super hot summer and people’s air conditioning is breaking. And so I guess the newscasters found him and just did this random interview and had no idea they’re talking to one of the world’s most famous philosophers of religion. And here’s this guy who’s so brilliant when he is doing philosophy of religion, yet when it comes to an air conditioner, it’s just a befuddling thing. But I’ve got to play it for you

Speaker 6:

Have been booked ever since it got hot outside. But we found out today there are some things that you can do to prevent your air conditioning unit from looking like this.

Alvin Plantinga:

Like I say, you’ve got to have a PhD in engineering just to use your thermostat. And that seems over the top to me.

Dr. Ben Arbor:

It’s only five degrees cooler inside Alvin Plantinga’s house than it is outside today. Sweltering heat with no relief for three days in a row.

Alvin Plantinga:

It’s not real nice. If you live in Arizona you get used to it, but we don’t. And it’s right after a really cold kind of wet spring. So we weren’t really up for that at all. It was not that pleasant.

Trent Horn:

And then it goes on to give you tips about how to service your air conditioner. But I love it when I first saw that, I’m like, “Alvin Plantiga’s being interviewed randomly on a newscast.” I love that this guy is like super genius, smart, but it’s so funny, you can meet someone who’s a super genius and then they go to the thermostat, they’re like, “How in the world do you program this thing?” I mean maybe you feel that way yourself. So, all right, let’s go then to Plantinga’s argument for the existence of God, his modal ontological argument that deals with possibility and necessity rather than just strictly one’s conception of God. So here’s how he puts the argument.

It is possible that a maximally great being exists. So for Plantinga, a maximally great being is just one that is all powerful, all good, all knowing, and always exists, could never fail to exist. So what does that mean? If it is possible that a maximally great being exists, than a maximally great being exists in some possible world. So a possible world is not like an alternate dimension according to modal logic. A possible world is just a description of how the world could have been different. So we could say I might’ve chosen to do a different episode today than on the ontological argument. Maybe I could have done one on Anselm’s satisfaction theory of the atonement. Or you could have chosen to not listen to the podcast at all today. I am glad we don’t live in that possible world. I’m glad we live in the one where you are listening to the podcast right now. But Plantiga’s point is that if a maximally great being, all powerful, all knowing, all good, exists in one… If it’s possible that kind of being exists, then that being must exist in a possible world or a description of how the world could have been different. So if it’s possible that a maximally great being exists, then a maximally great being exists in some possible world.

The next premise, if a maximally great being exists in some possible world, then it exists in every possible world. Because by its definition, this is not like Anselm’s description, it’s strict modal logic, that if this maximally great being by definition is one that exists necessarily, so if it exists in some possible world, in some description of reality, it wouldn’t be maximally great unless it existed in every other possible world. So it wouldn’t be a maximally great being if it couldn’t exist if the sky was pink, or if there were two suns instead of one sun, like Tatooine in star Wars. If there was a possible world where the conditions were different and this being could not exist, it wouldn’t be God. It wouldn’t be maximally great.

So, I’m going to keep going through it so your head doesn’t spin too much. We start, it’s possible, a maximum great being exists. If it’s possible a maximum great being exists, then that being exists in some possible world. But if it exists in one possible world, it wouldn’t be maximally great unless it existed in all possible worlds. So if it exists in one, it’s got to exist in all possible worlds. Now, here’s where it gets interesting. If a maximally great being exists in every possible world, then it exists in the actual world. Because remember our world, a possible world is a description of reality, a coherent description of reality. Our world, there is a coherent description of reality. We can’t read it for our world, of course, that’d be too long. But our world is a possible world. Because think about it, anything that is actual is possible, right? Otherwise it wouldn’t be actual. It’s a possibility. So if a maximally great being exists in every possible world then it exists in the actual world.

And if a maximally great being exists in the actual world, then a maximally great being exists. Therefore, a maximally great being exists or God exists. Chutzpah again, right? You’re like, “Oh wow, does this really work? Is there some kind of trick with this argument?” Well, here’s a critique of it from Arnold Guminski. He is an atheist at the Secular Web, a very well known website with essays that are critical of arguments for God. And this is what he says, “It is generally agreed that the modal ontological argument, Plantinga’s modal ontological argument, it’s generally agreed it’s formally valid.” So what that means is that even Guminski will say there’s no fallacy here. There’s no error in the reasoning.

And I think that it is fairly obvious, assuming that a maximally great being is defined as one that exists in every possible world, it’s obvious if a maximally great being exists in some possible world then that being exists in all possible worlds and therefore in the actual world. So all right, why doesn’t Guminski believe in God? Why doesn’t this convince everybody? Guminski goes on to the point that everybody quibbles about. This is the sticking point for most people, the controversy. In the whole argument, it was the first premise that’s controversial, even if you didn’t catch it at first. The critical question is whether premise one, that it is possible a maximally great being exists, is true or is warranted, that its plausibility is greater than its negation. Because some philosophers will say, “Well, I could just run the argument backwards. I could say it’s not possible that a maximally great being exists, and therefore a maximally great being does not exist in a possible world, does not exist in every possible world, does not exist in the actual world. Therefore, God does not exist.” So some philosophers will just try to run the argument in reverse.

Ben Arbor, in his interview with Cameron Bertuzzi, he notes how when atheists try to combat this argument, if they’re not even willing to grant, remember premise one is just it is possible that God exists, that if you’re not even willing to grant that, then aren’t you kind of begging the question against God? Here’s how Arbor puts it in his interview with Cameron Bertuzzi,

Dr. Ben Arbor:

Now certain skeptics and atheists are going to want to get off the train right here and say, “See, yep, right there, that’s the problem. And so I’m just not willing to grant that it’s possible that God exists. I’m not willing to say that.” And then I say, “Okay, well if, if you don’t even think it’s possible that God exists, well then you’re begging the question against God’s existence from the get go. Because now we can’t even have a discussion.” Because you’re wanting to say from the get go, I don’t think God exists. Now let’s have a discussion and try to figure out whether or not God exists. And then on the other side of the discussion, they find out, see, God doesn’t exist. And I say that’s begging the question. Because right at the beginning you said as part of the argument, God does not exist, I’m not even going to admit that it’s possible that God exists. And then you have your discussion and then on the other side you get to therefore God does not exist. That’s not an honest intellectual discussion. Doesn’t mean if God doesn’t exist, there’s nothing wrong with starting there. But if you’re trying to have a conversation about whether or not God exists, it begs the question.

Trent Horn:

So that’s one point. I think Arbor raises a fair point here. A lot of atheist might say, “Well we’re dealing with two different kinds of possibility. Epistemic, which is for all we know God exists, or metaphysical, which is God is a legitimate possibility.” And this gets really hard in these kinds of arguments as to what is possible and what’s not. It seems pretty clear, it’s possible you could have chosen to not listen to this podcast. You try to think of other examples, is it possible that iron could float in another world? Well, if it did, would it stop being iron? Would it just be some other kind of substance that we’re not familiar with? So I think that’s where some atheists would kind of counter back here about possibility.

But I do think that the… For me when it comes to this kind of argument, if you do think God is a legitimate possibility, a real possibility, you’re not convinced, but you’re like, “Yeah, there could be a maximally great being that has all these properties, that that makes sense. It’s not something that’s beyond the realm. It seems very real to me as a possibility. It’s not something that’s just going to turn out to be some kind of logical contradiction that I was completely unaware of.” Then this argument may be persuasive to you. Brian Leftow, who is a philosopher at Oxford, really good philosopher of religion at Oxford university, he has a video where he talks about the ontological argument. He describes it, and then he talks about the possibility principle and how it’s very controversial to people, and how he thinks one could buttress it based on things we observe about how people interact with God. So let me play that clip for you.

Brian Leftow:

Why doesn’t everybody therefore believe in God? Because there’s a lot of controversy about the possibility premise. That’s where really push comes to shove. A lot of philosophers, including people who are very friendly to the ontological argument, like Alvin Plantinga, think you can’t really support the possibility premise in any sort of forceful way. And so you’re left with kind of a stalemate. The argument tells you that if it’s possible that God exists then he exists, but it leaves you still kind of undecided because it doesn’t support the idea that possibly God exists.

Where I’d like to come into the debate is with an attempt to show that, well, it is possible that God exists, that you can actually give some kind of decent argument for this. And one thing I’m currently exploring at the moment is the following thought. People report seeming to see God. I’m not saying that people really do see that would be a whole different consideration. But people seem to see God, it seems to them that God is present in their experience. No one ever reports seeming to see a round square or seeming to see a four-sided pentagon or anything like that. Impossible objects do not show up in people’s experience. And notice when I say show up in people’s experience, I’m not saying that they’re really there and making you experience them. I’m just saying when you talk about the kinds of experiences people have, they don’t seem to include experiences of impossible objects. So here’s the thought. It seems to people that God is present, but it never seems to people that something impossible is present. Conclusion, from the fact that people have seeming experiences of God, possibly God exists.

Trent Horn:

And this is interesting to buttress the argument, so I think that the future of the ontological argument, I don’t see it as being one on its own that would prove God exists, but it’s kind of the sriracha sauce to your unappetizing bland meal or whatever you like to put on. I love cilantro aioli myself. It’s something that zests it up and makes it just right. You can’t have it on its own. Are you really just going to drink sriracha sauce on your own? Are you really going to just spoon feed yourself a bunch of cilantro aioli? Well I might. It is delicious. No, it’s something that works with other arguments. So what Leftow is doing here when he appeals to experiences, where now it’s not a strict ontological argument anymore because we’re not going straight from the definition of God, we’re going from experiences people have to show God is a real possibility. And if he is, then he exists in every possible world.

So this is how Plantinga talks about the argument. He says, “Our verdict on these reformulated versions of St. Anselm’s argument must be as follows. They cannot perhaps be said to prove or establish their conclusion, but since it is rational to accept their central premise, they do show that it is rational to accept that conclusion.” So the argument, I think the ontological argument is one for someone who is near to believing in God of a particular philosophical bent. Most people who hear this argument, it sounds like a trick. They’re not even willing to entertain it. So that’s why I don’t share it too much with people. But some people who might have a quirky philosophical sense of wonder, this argument, combined with other observations about God and possibility in the world, may just be enough to move them to believe. We have to be prepared to offer people all different kinds of arguments and reasons for God, both rational and even non-rational. Some people will believe in God because they have an argument and they reach the conclusion, and they’re like, “That makes sense. There is a God.” Other people will just be standing in a St. Chappelle or Notre Dame looking at the stained glass windows and see the reflection and hear a Gregorian chant and say, “Yeah, God exists.” Rational and non-rational. Notice non-rational is not irrational, it just means it affects you as a human person in a different way.

And I hope I, this podcast, has affected you as a human person in a multitude of ways, rational, non-rational, everything in between to give you tools to help build up the kingdom of God, one person, one conversation at a time. Thank you guys so much.

Please pay for me. Please pray for me. I don’t know, I’ve been feeling… I guess now is this confession time? I’ve been feeling down a little bit. It took me a while even to just record this episode. Why might I be feeling down> I don’t know, thousands of people are dying from a pandemic. We’re all locked down. We don’t know when this is going to end. And I always tried to be cheery and chipper, but it starts to get to after a while. Maybe this is getting to you too. So when this episode is done, I’m going to say a prayer for you, whoever you are listening, if you’re struggling right now, just say a prayer for me and my family. I think we have to pray for one another even if we’ve never met. And maybe in the future I will get to meet you. I’m hoping September, things will be good, we could have our Catholic Answers conference or conference again. You could come and meet us if you’re ever down in San Diego or come to the office. I sure would like to meet you if that could ever happen. So you take care. Have a great day. I just hope that you have a very blessed day.

If you liked today’s episode, become a premium subscriber at our Patreon page and get access to member-only content. For more information, visit Trenthornpodcast.com.