Is devotion to the Divine Mercy an innovation or something consistent with the traditions of the Church? We sat down to get the answers from Fr. Hugh Barbour on Catholic Answers Focus.

Cy Kellett: Divine Mercy Sunday is approaching. What is the Divine Mercy?

Cy Kellett: Hello and welcome again to Catholic Answers Focus. I am Cy Kellett, your host. Thank you so much for joining us. Today we talk about…is it an innovation of the modern Church? Is it an imposition into the liturgical calendar? What is it? It’s the Divine Mercy. We will ask our chaplain, Father Hugh Barbour, about that. Father Hugh is the former prior of Saint Michael’s Abbey up in Orange County and, as I said, our chaplain now. Hello, Father Hugh. Thank you for being with us.

Fr Hugh Barbour: Happy to be here.

Cy Kellett: All right. So, maybe those were a little bit snarky, those questions that I started with.

Fr Hugh Barbour: Yes, but they all have an answer.

Cy Kellett: Okay. That’s what I’m always confident-

Fr Hugh Barbour: A devastatingly convincing answer.

Cy Kellett: I am ready to be devastatingly convinced.

Fr Hugh Barbour: The naysayers or critics, if you can imagine, of the Divine Mercy Devotion, I will respond to them.

Cy Kellett: And there are critics of the Divine Mercy Devotion.

Fr Hugh Barbour: It’s unbelievable, but there really are. There have been for many decades.

Cy Kellett: Well, you’ve got to be careful not to get too much mercy. You wouldn’t want God going around forgiving everybody.

Fr Hugh Barbour: Well, I don’t know if it’s quite that, but anyway…

Cy Kellett: All right.

Fr Hugh Barbour: Something like that.

Cy Kellett: So I don’t know. I always get into these somewhat impish moods when you’re around. I’m not sure what in you brings that out in me, but-

Fr Hugh Barbour: It’s contagious, see.

Cy Kellett: Is it?

Fr Hugh Barbour: I give it to you. Yeah.

Cy Kellett: Are you impish?

Fr Hugh Barbour: Yeah. Impish I wouldn’t say, but-

Cy Kellett: Maybe sylvan?

Fr Hugh Barbour: Subversive maybe.

Cy Kellett: Subversive! Okay, all right. Well, first of all let us begin with: there is an actual Divine Mercy Sunday now. And it is the Octave of Easter, which would seem to be a quite honored place for a Sunday.

Fr Hugh Barbour: Yes. Just about as high as you could get.

Cy Kellett: So how did we end up with this?

Fr Hugh Barbour: Well, the actual designation of the Octave Day of Easter being Divine Mercy Sunday is the result of a request made by our Lord to Saint Faustina Kowalska, a Polish sister, in the first half of the 20th century in the twenties and thirties, to ask the Church, the Holy Father, to establish that Sunday, the Octave of Easter, as the Feast of Divine Mercy.

Fr Hugh Barbour: And that would seem like a wild innovation because the Octave of Easter is very venerable. It’s called Low Sunday or White Sunday, the Dominica in Albis. And it has liturgical texts that go way, way, way back. And so it would seem odd to indicate a feast on a day which was already taken. The other requests our Lord has made for feasts have always been for days that weren’t taken. So he asked Blessed Juliana of Mont Cornillon for the feast of Corpus Christi. That was going to be the Thursday after Trinity Sunday.

Fr Hugh Barbour: So, outside the Easter season and a Thursday that wasn’t already occupied.

Cy Kellett: Less dramatic.

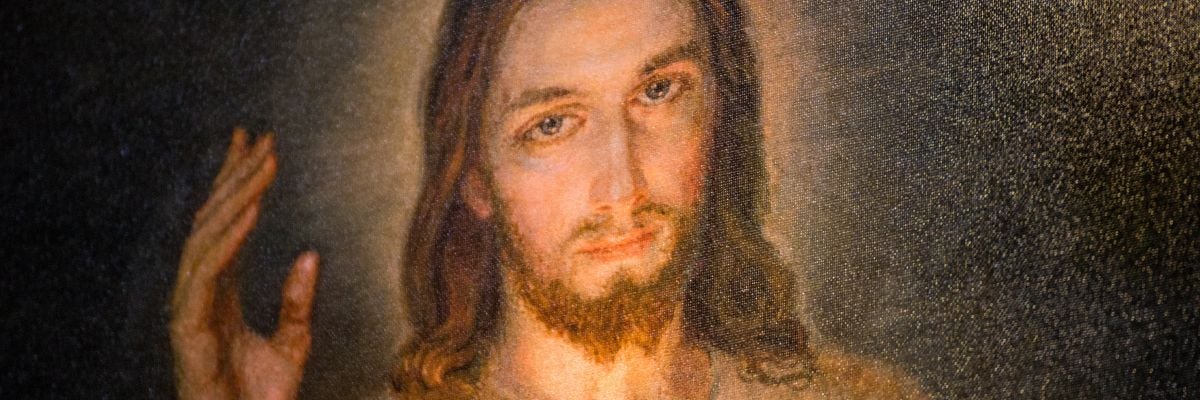

Fr Hugh Barbour: Right. And then the Friday after Corpus Christi, Our Lord asked for the Feast of His Sacred Heart of Saint Margaret Mary. And so there’s already precedent. Two major and very popular and well-beloved feasts to the Church were from direct requests by our Lord to these holy women to whom he appeared, and the church ratified both of those in her permanent practice so that those are solemnities in the universal calendar. So the request made by our Lord to Sister Faustina, it goes in the same direction. And what we see there is a development of the themes of Lent and the Paschal season. And particularly, if you consider the image of the Divine Mercy, which is well known now, which our Lord asked to be painted–he even told her, “Don’t worry. It doesn’t have to look all that good,” and I’m consoled by that because I don’t like most of the ones I see–but the original one is the best, the one that was actually originally venerated in Vilnius. And that’s the one copy which we have in our chapel here at Catholic Answers.

Cy Kellett: Right.

Fr Hugh Barbour: So just FYI. But the image there shows our Lord coming through the door of the upper room on the evening of Easter and there are rays of red and white flowing from his heart to symbolize the blood and water, the fluid from his side, but now in the glory of the resurrection shown in their power to bestow pardon and consolation and strength on people. And so that’s the image. Well, lo and behold, imagine, the Church didn’t have to change any of the texts for Divine Mercy Sunday. She kept the the texts exactly as they were always because the Collect of the Mass for that day refers to “by what water they’ve been washed and by what blood they have been redeemed.”

Cy Kellett: Oh, so there it is.

Fr Hugh Barbour: The theme was already there. Okay.

Cy Kellett: Yeah.

Fr Hugh Barbour: And so our Lord knew what he was doing, in other words. In addition to that, he asked for the Novena to the Divine Mercy, which gets a lot of criticisms from liturgy types who say, “Why would you start a Novena on Good Friday? This is like the most important liturgical season and then you’re adding a Novena on everything.” But people that are listening should not be scandalized. Maybe they don’t know that there are people like this, but there are, who make these complaints. What is interesting to me, and from my study of ancient liturgy made me make the connection, is that in the Church’s practice regarding Lent, of course you have Ash Wednesday, which is the day of the “expulsion of the penitents.”

Fr Hugh Barbour: So those who were doing penance for their sins before Easter, they were put in sackcloth and ashes and then they were taken out of the church and they assisted at the liturgy in the vestibule but not in the nave as a sign of their penitence. And also distinguished them from the catechumens who are starting out for the first time. And so the catechumens get all the attention because they’re the kids and the people that blew it after baptism, they do their penitential thing in the back of the church.

Fr Hugh Barbour: But on Holy Thursday, the Church reconciled those penitents with a Mass which included their absolution from their sins because they had completed their penance. And so Holy Thursday had a Mass. Now we have two Masses for Holy Thursday, the Chrism Mass and the Mass of the Lord’s Supper. Chrism Mass is usually celebrated on some other day to make it convenient for the diocesan priests to come.

Fr Hugh Barbour: And then of course is a Mass of the Lord’s Supper. But in the Patristic Period, in the Middle Ages, there were three Masses. There was the Chrism Mass, and there was the Mass for the reconciliation of the penitents, and then there was the Mass of Lord’s Supper. Then they were admitted back in the church, so the first day they could come back into the church and worship with the rest of the faithful was Good Friday. Now interestingly, and this is just if you can … it’s “a long prologue to a tale,” as Chaucer would say. All right? But it’s very important to see. The Novena goes from Good Friday to the Saturday, the eve of the Feast of Divine Mercy, the Saturday of the Octave of Pentecost. What they did in antiquity was, so as not to take away anything from the splendor of the newly illuminated catechumens who were baptized and they receive their communion on Easter, interestingly in the ancient Church, the penitents did not receive their Easter communion until the Octave day.

Cy Kellett: Oh!

Fr Hugh Barbour: And of course, they regarded the whole … the idea of an Octave is that the whole week is the same feast day, because you say, in the Roman Canon you say, “On this day.” And you say that for the whole eight days, just as you, at Christmas and Easter, in the Roman Canon, refer to a single day, because it’s the whole cycle of the feast, extended you might say.

Fr Hugh Barbour: So the penitents received the full complement of their absolution and everything on that day when they were admitted to communion again. So I think when our Lord said he wanted this feast day and then he also said he wanted an indulgence granted with full remission of temporal punishment, plenary indulgence to those who would adore the Blessed Sacrament and venerate the picture of Divine Mercy and so on, all these other possibilities on that day, I think our Lord was actually restoring, you might say, the spiritual essence of that ancient practice, with the people being given a sense of “Lent has gone by, and now I’m, relatively speaking, reconciled to the Lord. And so I started this Novena in preparation for the full remission of my sins and penalties due to sin on the Feast of the Divine Mercy.” So I don’t hear that said very much, and Sister Faustina didn’t say it in so many words, but I discovered it when I read an article in St. Thomas’ Summa–which if you know the Summa, you can take a look at it–on the Church’s rite of public penance. And he describes it there. And when I read it, I goes, “My goodness, this is exactly-”

Cy Kellett: Isn’t that something?

Fr Hugh Barbour: So I thought, “There’s a parallel here.” That’s a lot of verbiage, but basically, let’s just say there’s a lot more purely liturgical and traditional justification for this feast than just “It’s a devotional addition to an otherwise laden liturgy.

Cy Kellett: Ah, right. It’s not just an innovation. It’s a recovery in many ways.

Fr Hugh Barbour: It fits exactly the themes. And then, if you add to it the tradition of the Eastern Church and the Western Church, the Gospel for the Sunday, the Octave Day of Easter, is that of our Lord appearing in the upper room and saying, “Peace be with you.” And that’s precisely the image of Divine Mercy. It’s our Lord coming miraculously through the closed door and giving his peace to those present and in the … So it includes not only the Roman Rite, but also the Byzantine Rite because they call that Thomas Sunday, the Sunday which they commemorate doubting Thomas and our Lord’s visit to the apostles. And that’s when he puts his hand in his side.

Fr Hugh Barbour: So in Eastern Churches they have exposed in front of the altar, usually they have the icon that represents the feast day or the major feast of the Church’s year or the saint. And so they have the icon of the Thomas putting his hand on the Lord’s side. And you can see clearly behind the Lord in those icons, the door, and so in the side from which in the Divine Mercy picture of the blood and water rays come forward. So you realize this is just-

Cy Kellett: It all goes together.

Fr Hugh Barbour: Right. It all goes together.

Cy Kellett: Perfect.

Fr Hugh Barbour: So Our Lord is pretty much uniting East and West, uniting ancient practice with modern practice, and restoring the spiritual essence of these seasons.

Cy Kellett: So, Faustina Kowalska is a Polish nun.

Fr Hugh Barbour: Sister, right.

Cy Kellett: And then the Church … there’s some translation problems, as there often are in these cases, and also there’s people who are opponents of the whole Divine Mercy thing, so the whole thing gets kind of suppressed and-

Fr Hugh Barbour: Well, what happened was that the Polish bishops approved of the devotion.

Cy Kellett: OK.

Fr Hugh Barbour: And it spread in Poland in the ’40s and ’50s with the images in the churches and everything. But then in Rome, a Cardinal Ottaviani, who was a great man and a very prudent man, suffered a lot for the Church, but he didn’t like private revelations very much, because they were proliferating at breakneck speed. So he just kind of had an automatic default mode: “Sorry. No.”

Cy Kellett: I see.

Fr Hugh Barbour: And so even though it had been approved by the Polish bishops and was well-established in Poland, he canned it, basically. He said to the Holy See, he said, “No, you can’t.” So they forbade the devotion to Divine Mercy in the forms presented by a Sister Faustina; but that little technicality allowed them to continue to produce various kinds of images of our Lord with the two rays coming from his heart. But they altered it in such wise that it wasn’t exactly what she promoted.

Fr Hugh Barbour: And so you have … And I remember as a kid in the seventies, there’s these holy cards of Jesus, King of Mercy. And they would have the sacred heart with the rays and then angels around him. They altered it a little bit and then they had a Chaplet of Divine Mercy that wasn’t exactly the one that she indicated. So they were able to get by with a letter of the law. But when John Paul II became pope, one of his first things was to get the Holy Office, the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith, to rescind the prohibition on the spreading of the devotion.

Cy Kellett: Had he been exposed to it as a young man in Poland?

Fr Hugh Barbour: Oh yeah, because in Poland it was everywhere. It was everywhere. And they didn’t make them take the images down that were already up. They just wanted to put a … and it’s probably prudent just to kind of …

Cy Kellett: The kibosh.

Fr Hugh Barbour: It was something the Church needed–imagine this: if it had not been suppressed by Ottaviani, then everyone would have said, “Well that’s a pre-Vatican II devotion. I remember that. Let’s just chuck that,” you know? But it wasn’t at that point. No one had experience of it, and it became picked up by the charismatics especially-

Cy Kellett: Isn’t that wonderful?

Fr Hugh Barbour: … they were very keen on it. I think it was a providential moment. So, I remember in Rome as a student, there were a little bookshops that sold devotional things, and when it became acceptable again, little by little people got the literature and whatnot. And I remember at a time when it was almost impossible to find anything in English. You had to read Italian or Polish or something to get the information. But John Paul II pulled the prohibition and then it just exploded. And of course then he became the pope who actually approved the devotion completely, fulfilling her prophecy.

Cy Kellett: I feel like the Holy Spirit is a planner.

Fr Hugh Barbour: Yeah.

Cy Kellett: Plans ahead.

Fr Hugh Barbour: Yeah.

Cy Kellett: All of this comes together in such a beautiful way.

Fr Hugh Barbour: Yeah, right.

Cy Kellett: But I want to ask you about Poland in particular. Before I go on, I want to get a little more information from you in our second part here about what it means to be a follower of the Divine Mercy or what is the message and all that. But first I want to ask you about Poland because it strikes me that we have this, the greatest Catholic figure of the twentieth century, this Polish guy. But it’s also true that the greatest crimes of the twentieth century are committed right there in Poland. I mean, most people would think the word Auschwitz represents the nadir of maybe of all of human history.

Fr Hugh Barbour: But that wasn’t a crime committed by the Poles.

Cy Kellett: No, no, that’s right. In many ways committed against them.

Fr Hugh Barbour: And they’re fighting right now very strongly to make sure that that point is made.

Cy Kellett: It should be. Right. Exactly.

Fr Hugh Barbour: Cuz people are trying to demonize the Polish people now.

Cy Kellett: But I have the impression of a connection here, in that Jesus is excluding nothing from his mercy. He’s going to the very scene of the crime of the twentieth century.

Fr Hugh Barbour: Yeah, it was horrible.

Cy Kellett: Even preceding it, even going there before it even happens, to give us the sense of the depth of his mercy.

Fr Hugh Barbour: Yeah.

Cy Kellett: Do you think that I have a correct impression?

Fr Hugh Barbour: Oh, I think you have a very correct impression. Yeah.

Cy Kellett: Yeah. Thank you for clarifying it was not the Poles that committed that crime. I didn’t mean that.

Fr Hugh Barbour: Yeah, but I wanted to say that because right now there’s a lot of … Because the Polish government is kind of very pro-Catholic and very traditional in its moral orientation, and-

Cy Kellett: We can’t have that. That’s anti-EU.

Fr Hugh Barbour: … Now they’re going on claiming that the Poles collaborated with the Germans and all that sort of thing. And the Poles didn’t get along with the Germans, and they were kind of mean to them after the war.

Cy Kellett: Kind of mean?

Fr Hugh Barbour: Got them, pushed them all out of northern Poland. But that’s very different from the Holocaust.

Cy Kellett: Right. It is indeed and the-

Fr Hugh Barbour: That was a historical tension between these two peoples which was not based upon some kind of ideology. It was based upon their association over the years.

Cy Kellett: All right.

Fr Hugh Barbour: Because the Poles were always being ruled either by the Russians or the Germans.

Cy Kellett: Or the Germans.

Fr Hugh Barbour: Right.

Cy Kellett: Yeah.

Fr Hugh Barbour: And then when the Poles got a kingdom of their own, then they ruled over the Lithuanians and the Ukrainians.

Cy Kellett: It’s the way of the world.

Fr Hugh Barbour: Everybody finds out how to run things.

Cy Kellett: Indeed. Thank you, Father. I look forward to continuing this conversation with you next week, and thank you to everybody who joins us here on Catholic Answers Focus. If you like what you hear, would you please share Focus with other people? Just send them over to CatholicAnswersLive.com where they can give us their email and we’ll send them out a notice each time there’s a new Focus posted. Thank you so much. We’ll see you next time, God willing, on Catholic Answers Focus.